- Contributions from leading authorities

- Informs and updates on all the latest developments in the field

Published since 1953, Advances in Virus Research covers a diverse range of in-depth reviews, providing a valuable overview of the current field of virology. Contributions from leading authorities Informs and updates on all the latest developments in the field

Front Cover 1

Advances in Virus Research 4

Copyright 5

Dedication 6

Contents 8

Contributors 10

Chapter 1: Comparison of Lipid-Containing Bacterial and Archaeal Viruses 12

1. Introduction 13

1.1. Origin of lipids in prokaryotic viruses and their detection 14

2. Function and Significance of Lipids in Prokaryotic Virus Life Cycle 29

2.1. How prokaryotic viruses acquire their lipids 32

2.1.1. Viruses with an external membrane 32

2.1.2. Viruses with a membrane underneath the icosahedral capsid 33

2.1.3. Viruses with lipids as structural protein modifications 34

3. Currently Known Lipid-Containing Bacterial and Archaeal Viruses 35

3.1. Icosahedral viruses with an inner membrane 35

3.1.1. Lipids in the corticovirus PM2 with a circular supercoiled dsDNA genome 36

3.1.2. Lipids in PRD1 and related viruses 38

3.1.3. Lipids of PRD1 form an icosahedrally ordered membrane 39

3.1.4. PRD1 genome delivery occurs through a membranous tunneling nanotube 40

3.1.5. Assembly and packaging of internal membrane-containing bacteriophage PRD1 42

3.2. Enveloped icosahedral viruses: Phage .6 and its relatives 43

3.2.1. Involvement of the membranes in .6 entry 44

3.2.2. How .6 acquires its membrane envelope 45

3.2.3. Lipids of the .6 virion and its host 46

3.3. Vesicular pleomorphic viruses 46

3.3.1. Asymmetric lipid vesicles as viruses 48

3.3.2. Bacterial vesicular viruses 50

3.4. Prokaryotic viruses with helical symmetry: With or without a membrane 51

3.4.1. Lipothrixviruses: Helical viruses with a membrane envelope 51

3.4.1.1. Alphalipothrixviruses 52

3.4.1.2. Betalipothrixviruses 52

3.4.1.3. Gammalipothrixviruses and deltalipothrixviruses 53

3.5. Lemon-shaped viruses are specific for archaea 54

3.5.1. Viruses with one short tail 54

3.5.2. Viruses with one or two long tails 56

3.6. Archaeal spherical viruses with helical NCs have an envelope 57

4. Conclusions 58

Acknowledgments 60

References 60

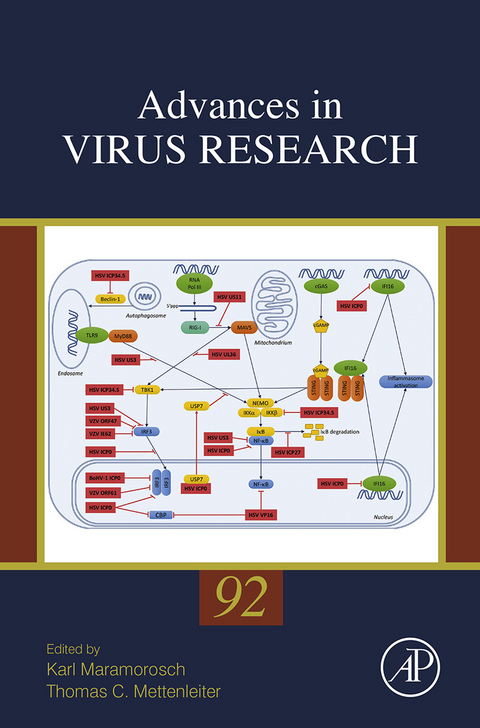

Chapter 2: Innate Recognition of Alphaherpesvirus DNA 74

1. Introduction 75

1.1. Alphaherpesviruses 75

1.2. Immunity to alphaherpesviruses 77

1.3. Innate DNA sensing 78

2. DNA Sensors 81

2.1. TLR9 81

2.2. Discovery of intracellular DNA sensors 86

2.3. DAI 86

2.4. AIM2 88

2.5. IFI16 89

2.6. cGAS 92

2.7. RNA Pol III and RIG-I 94

3. Accessibility of Viral DNA to DNA Sensors 95

4. Evasion of DNA-Induced Signaling 96

5. Relevance for Vaccine Design 99

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective 101

References 102

Chapter 3: Molecular Biology of Potyviruses 112

1. Introduction 113

2. Genera of the Family Potyviridae and the Main Differences in Genome Structures 114

3. Biological and Biochemical Features of Potyviral Proteins 116

3.1. P1 117

3.2. HCPro 118

3.3. P3, 6K1, and PIPO 125

3.4. CI 126

3.5. 6K2 and NIa 127

3.6. NIb 128

3.7. CP 129

4. Virus Multiplication 130

4.1. Subcellular localization of potyvirus multiplication 130

4.2. Viral and plant factors involved in potyvirus multiplication 132

4.3. Putative functions of these factors during potyvirus multiplication 136

5. Virus Movement 139

5.1. Intracellular and cell-to-cell movements 139

5.2. Long-distance movement 143

5.2.1. Viral determinants involved in potyviral long-distance movement 145

5.2.2. Host factors involved in the restriction of long-distance movement 147

6. Virus Transmission 149

6.1. Transmission by aphids 149

6.2. Seed transmission 153

7. Plant/Potyvirus Interactions in Compatible Pathosystems 155

7.1. Evolutionary abilities of potyviruses to adapt to their hosts 156

7.2. HCPro: A key pathogenicity determinant as suppressor of RNA silencing 163

7.3. Symptomatology 166

8. Biotechnological Applications of Potyviruses 176

9. Concluding Remarks 177

Acknowledgments 178

Note Added in Proof 178

References 178

Chapter 4: Immune Evasion Strategies of Molluscum Contagiosum Virus 212

1. Introduction 213

2. Characteristics of the MCV Genome and Insights into MCV Replication 214

3. MC Lesion Development 215

4. Characterization of MC Lesions 217

4.1. Initial stages of infection 217

4.2. Host cell response to MCV infection 218

5. Immune Responses to MCV Infection 219

6. MCV Epidemiology 220

7. MCV Diagnosis and Treatment 222

8. Current Roadblocks in Propagating MCV in Tissue Culture Systems 223

9. MCV Immune Evasion Mechanisms 225

10. Limitations and Caveats When Studying MCV Immune Evasion Proteins 225

11. The FLIP Family of Viral and Cellular Proteins 227

11.1. Introduction to FLIPs 227

11.2. Signaling events triggered by the TNFR1 227

11.2.1. Discovery of viral and cellular homologs of procaspase-8 229

11.2.2. MC159 and inhibition of apoptosis 231

11.2.3. MC160 and apoptosis 233

11.2.4. Gammaherpesvirus FLIPs and inhibition of apoptosis 234

11.2.5. cFLIP and apoptosis 235

11.3. The FLIP family and control of NF-.B activation 237

11.3.1. MC159: A protein that inhibits NF-.B activation 237

11.3.2. MC160, an NF-.B-inhibitory protein 239

11.3.3. The K13 vFLIP is an NF-.B-activating protein 240

11.3.4. cFLIPs and their functions in regulating NF-.B activation 242

11.4. The FLIP Family and Control of IRF3 Activation 243

11.4.1. MC159 and inhibition of IRF3 244

11.4.2. MC160 and inhibition of IRF3 245

11.4.3. cFLIP and inhibition of IRF3 245

12. Other MCV Immune Evasion Molecules 246

12.1. MCV MC54, an IL-18-binding protein 246

12.2. MCV MC148, a viral chemokine 247

12.3. MCV MC007, a pRb-binding protein 248

12.4. MC66, a glutathione peroxidase homolog 248

13. Conclusions 249

References 249

Index 264

Color Plate 272

Innate Recognition of Alphaherpesvirus DNA

Stefanie Luecke*; Søren R. Paludan†,‡,1 * Graduate School of Life Sciences, Universiteit Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands

† Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

‡ Aarhus Research Center for Innate Immunology, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

1 Corresponding author: email address: srp@biomed.au.dk

Abstract

Alphaherpesviruses include human and animal pathogens, such as herpes simplex virus type 1, which establish life-long latent infections with episodes of recurrence. The immunocompetence of the infected host is an important determinant for the outcome of infections with alphaherpesviruses. Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern recognition receptors is an essential, early step in the innate immune response to pathogens. In recent years, it has been discovered that herpesvirus DNA is a strong inducer of the innate immune system. The viral genome can be recognized in endosomes by TLR9, as well as intracellularly by a variety of DNA sensors, the best documented being cGAS, RNA Pol III, IFI16, and AIM2. These DNA sensors use converging signaling pathways to activate transcription factors, such as IRF3 and NF-κB, which induce the expression of type I interferons and other inflammatory cytokines and activate the inflammasome. This review summarizes the recent literature on the innate sensing of alphaherpesvirus DNA, the mechanisms of activation of the different sensors, their mechanisms of signal transduction, their physiological role in defense against herpesvirus infection, and how alphaherpesviruses seek to evade these responses to allow establishment and maintenance of infection.

Keywords

Alphaherpesviruses

HSV-1

TLR9

STING

Type I interferon

1 Introduction

1.1 Alphaherpesviruses

The Herpesviridae family comprises more than 130 virus species, which infect mammals, birds, and reptiles. Herpesviruses are enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses (Fig. 1A), which usually lyse productively infected cells and establish latent infections in their hosts. Eight herpesviruses are known to cause disease in humans, most notably in children and immunocompromised individuals. The family is divided into three subfamilies, alpha-, beta-, and gamma-herpesviruses. This division was originally based on biological similarities and later confirmed by genome sequencing (Pellett & Roizman, 2013).

Alphaherpesviruses are characterized by a relatively broad host range and fast reproduction during lytic infection compared to other herpesviruses (Pellett & Roizman, 2013). They contain three virus species pathogenic to humans (herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1, also called human herpesvirus 1), herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2, also called human herpesvirus 2), and varicella zoster virus (VZV, also called human herpesvirus 3)) and many pathogens of veterinary importance, notably Marek's disease virus (MDV, also called gallid herpesvirus 2) and pseudorabies virus (PRV, also called suid herpesvirus 1).

Herpes simplex viruses are ubiquitous human pathogens, which lytically infect epithelial cells of mucosal surfaces and the skin and afterward establish latency in the cell bodies of peripheral sensory neurons innervating the infected area. During latency, the viral genome persists in the nucleus of the host while the majority of viral genes are silenced. It can be maintained for the lifetime of the host organism. Reactivation from latency can be induced by a number of factors, including tissue damage, UV radiation, immune status changes, and stress, but can also occur spontaneously. In reactivation, virus particles produced in the neuronal cell body are transported along the axons by anterograde transport and infect epithelial cells again. HSV-1 usually causes recurrent cold sores at the lips (herpes labialis), while HSV-2 is often responsible for genital herpes infections (herpes genitalis). HSV may also spread to the central nervous system, leading to herpes encephalitis, cause disseminating herpes infections in neonates and immunocompromised individuals, and infect the eyes, often leading to blindness (Roizman, Knipe, & Whitley, 2013).

VZV is the causal agent of chicken pox after primary infection and of shingles (herpes zoster) upon reactivation. In primary infection, the virus usually infects epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract followed by infection of T cells in lymphoid tissues. This allows for transport of the virus to skin areas over the whole body, where viral replications result in the characteristic rash. VZV then establishes latency in peripheral sensory neurons. The virus can reactivate to cause shingles, which may be associated with serious neurological complications (Arvin & Gilden, 2013).

PRV first infects epithelial cells of the respiratory tract and then establishes latency in sensory neurons. The natural hosts for this virus are pigs, but it can also infect many other mammals such as cattle, sheep, and dogs. It is the causative agent of Aujeszky's disease, which is characterized by symptoms ranging from high mortality and severe central nervous system defects in suckling piglets, via abortions and stillbirths in pregnant sows, to fever and respiratory symptoms in adult pigs (Pomeranz, Reynolds, & Hengartner, 2005). MDV establishes latency in and causes oncogenic transformation of immune cells, especially CD4+ T cells, and lytically infects epithelial cells of inner organs and the skin in chickens, leading to a variety of clinical symptoms including chronic polyneuritis and visceral lymphoma (Osterrieder, Kamil, Schumacher, Tischer, & Trapp, 2006).

Herpesviruses enter their host cells by fusion of the viral lipid envelope with the plasma or endosomal membrane, which is initiated by interaction of viral glycoproteins in the virion envelope with cell surface receptors. Upon viral entry, the tegument proteins, located between the viral envelope and the capsid, are released into the cytoplasm and interact with host factors to create a favorable environment for the virus. In permissive cells, i.e., cells that allow productive replication of the virus, the icosahedral capsid containing the viral dsDNA genome moves along the microtubule network toward the nucleus, where the viral DNA is translocated through the nuclear pores. In the nucleus, the viral genome circularizes (Fig. 1). Silencing of viral gene expression can lead to the establishment of latent infection. During lytic infection, expression of viral genes takes place in three stages, immediate-early (responsible for subsequent viral gene expression and immune evasion), early (replication of viral DNA), and late (formation and release of progeny virions), and eventually leads to multiplication of the viral genome and to assembly and release of new virus particles (Arvin & Gilden, 2013; Roizman et al., 2013). However, some cells, such as macrophages in case of HSV-1, are nonpermissive for the virus, i.e., productive replication does not take place. Even in permissive cells, not all viral particles lead to productive infection. It is suspected that this is partly due to the early innate antiviral response of the cells (Paludan, Bowie, Horan, & Fitzgerald, 2011).

1.2 Immunity to alphaherpesviruses

As with most infectious diseases, immunity to alphaherpesviruses relies on innate and adaptive immune responses. One of the first responses upon detection of a herpesvirus in an infected cell is the production and secretion of interferons (IFNs), especially type I (IFNα and IFNβ), but also type III (e.g., IFNλ), and other proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Ank et al., 2008; Egan, Wu, Wigdahl, & Jennings, 2013). By paracrine and autocrine signaling, IFNs mediate a number of antiviral activities in infected and neighboring cells by the induction and expression of a variety of genes (interferon-stimulated genes, ISGs)...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.3.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete | |

| Studium ► Querschnittsbereiche ► Infektiologie / Immunologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-12-802425-9 / 0128024259 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-12-802425-6 / 9780128024256 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 7,2 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: PDF (Portable Document Format)

Mit einem festen Seitenlayout eignet sich die PDF besonders für Fachbücher mit Spalten, Tabellen und Abbildungen. Eine PDF kann auf fast allen Geräten angezeigt werden, ist aber für kleine Displays (Smartphone, eReader) nur eingeschränkt geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Größe: 9,5 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich