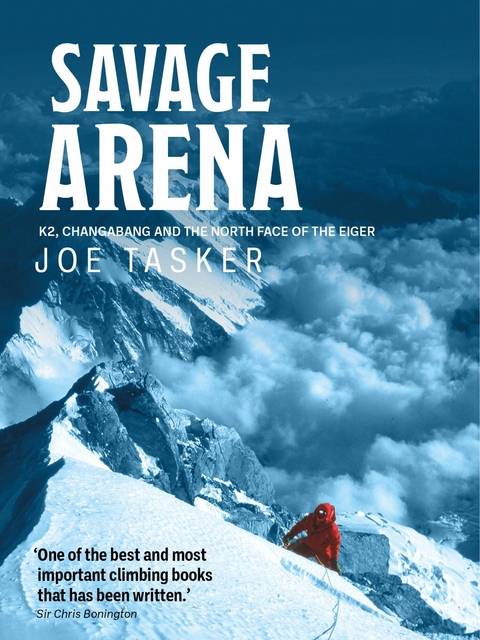

Savage Arena (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-906148-75-1 (ISBN)

CHAPTER TWO

It is Forbidden to Walk on the Track

THE EIGER

I

Ten years later I was on my way to climb the Eiger a second time. Our ascent in summer had been a traditional one. Though we had known more about that mountain by reputation and accounts than any other, we still had to go and climb it, and having climbed it we were coming back because it was the longest and most complex route we could think of and, if we dared admit it to ourselves, the most difficult. We wanted something substantial, something we could get our teeth into. We did not want to overcome a mountain with ease, we needed to struggle, needed to be at the edge of what was possible for us, needed an outcome that was uncertain. Sometimes I wondered if the climbing had become an addiction, if the pleasure of this drug had gone and only the compulsion to take it in ever stronger doses remained.

The brakes on the Anglia were terrible. We called in to see André in Switzerland, an engineering contractor for whom Dick and I had both worked instead of returning to Britain after the summer’s climbing in 1973. His foreman gave us a hand to mend the brakes and a tongue-lashing for driving such a suicidal machine. We did not have to tell them our plans, the name of the group of mountains was enough – the Bernese Oberland. Their concern was matched by their pride. I borrowed a crash helmet from Danielle, André’s cousin; my own had somehow been left behind.

In the Lauterbrunnen valley we found lodgings in the Naturfreundhaus, a hotel run by a kindly Frau Gertsch. She was surprised and pleased to find she had climbers staying rather than the periodic groups of skiers. We had the place to ourselves – long communal platforms of foam mattresses to stretch out on for beds, but none of the summer crowds to share them with.

When we returned from a five-day outing making an ascent of the North Face of the Breithorn, Frau Gertsch took us as sons. She assigned the second dining-room completely to us for sorting out and drying our gear.

The North Face of the Breithorn was a preparatory climb for us, something on which we could try ourselves out and get the feel of climbing in winter. There was deep snow all the way to the foot of the mountain and it took eight hours of agonising toil before the climbing started. Then for three days we steadily made our way up gullies of snow, turning to ice, and of loose rock held in place by ice. As a climb it was interesting, well within our capabilities. We did not want an epic, did not want to stretch ourselves so much that we would lose the drive for our real purpose. Winter climbing is solitary; we had the mountains to ourselves. A lone plane one day was the only sign of life we saw the whole time we were away in that frozen wilderness.

We had a few days’ rest after that, rest from climbing, not rest from activity. Dick went off on a nature trek on cross-country skis, shunning the contrived sport of skiing on a piste with cable cars, chair lifts and tows. He had worked in the resort of Montana one winter as a dish-washer. During the afternoon break he would hoist his skis onto his shoulder and walk up the piste rather than indulge in taking the téléphérique. In this way he became very fit but did not improve his skiing much as it took him all his time to walk up for a single run down. I did not find Dick much company. I took the train up to Kleine Scheidegg, the station at the foot of the Eiger, and skied below the dark wall of limestone, ice and snow, trying to absorb some impression from it, trying to attune myself to it, trying to penetrate its inscrutable aspect. At sunset I slid away, down to the cosy warmth of the Naturfreundhaus. It was time for us to make ready and go.

The Eiger and surrounding area.

Twenty rock pitons, 32 aluminium karabiners, 11 ice pitons, ice axes, ice hammers, crash helmets, we laid all the gear and food and clothing out on the tables in the dining-room. There was a lot of weight, but it was a huge wall and if we had to retreat we would need many pitons to drive into rock or ice to safeguard our descent. There was much snow low down, I had noticed, but the ice fields in the middle of the face seemed to be nothing but dark, hard ice. We expected our progress to be slow and we were consequently taking food for a week.

On 14 February, early in the morning, we joined the skiers who were boarding the train to Scheidegg to make best use of the morning snow. There were curious glances at our untidy appearance amidst the sleekly clad throng. There were hostile glances at the ice axes protruding from our bulging rucksacks; we did not fit into the normal pattern.

It was strange to think that the railway track continued up inside the mountain we were intending to climb. In order to reach the Jungfraujoch, a vantage point on a ridge between two valleys, a tunnel has been carved through two mountains. The ventilation holes from the tunnel open onto the lower part of the North Face of the Eiger and have sometimes been used to avoid descending the last few hundred feet by parties retreating in bad weather. I had not been able to locate through binoculars any sign of the entrance to these air shafts, and assumed that they were concealed deep beneath the snow. The idea of a train trundling up inside the mountains we would be living on for days was bizarre but it did not detract from the seriousness of the mountain, since the air vents are located low down where there are few difficulties.

When the train disgorged its load, the skiers busied themselves clipping on skis and Dick and I trudged off away from the crowds, into the shadow cast by the wall. There were hundreds of people around us but I felt quite alone. Our tracks led away from the ski pistes in a rising contour until, after an hour of wading through deep snow, we reached steepening ice, the start of the climbing. The crevasses along the foot of the face were covered by the winter snows.

Always I feel nagging doubts and uncertainties before a climb, always I wonder what I am doing launching out, away from more immediate pleasures and certain comforts. Now, faced with the long, unpredictable voyage ahead, up this wall, the feeling was stronger than ever, reinforced by the stray shouts of the tiny skiers in the distance. Dick, as ever, seemed unaffected by any such self-questioning and I wondered to what extent I rode on the wave of this determination.

The sky was clear, the air chill, but there was no wind. I felt I was lingering over the ritual of strapping crampons to boots, of uncoiling ropes and tying on, one of us to each end. We needed the points of the crampons to dig in to the steep ice in front of us, but there was much snow too. We sandwiched a layer of polythene between the crampon framework and the sole of each boot so that the snow would not stick, forming a heavy, unstable ball beneath each foot. Then Dick was off, no reasons for delay left, sack on his back, karabiners and pitons jangling from his seat harness, ice axe and hammer driven alternately into smooth ice and himself moving with increasing certainty upwards on the front points of his crampons.

In summer the lower part of the North Face is not difficult, the first 1,500 feet can be climbed in a few hours, up terraces littered with loose rocks, avoiding steep walls by taking a zigzag course along ledges. Now we were confronted by a largely featureless area of snow, broken only by infrequent outcrops of rock. Had the snow been firm, had it supported our weight, it would have made our task much easier, but we sank into it, knee deep, thigh deep, and beneath there was sometimes steep rock, sometimes ice. We could not see or feel the ledges up which we had zigzagged in summer, it was as if we were runners on a race track we knew but with a ball and chain on each foot.

Our ropes were 150 feet long. We had two, and each of us attached one end of both ropes with a karabiner to the harness round our waists. Like this, whichever of us was leading a pitch could climb for the full length of the ropes, clipping them one at a time, with karabiners, onto pitons or nylon loops on rock spikes, to safeguard movement upwards. With two lengths of rope there is more safety, but using the two alternately also prevents the friction of the ropes, as they run through karabiners, placed unavoidably in a zigzag manner, from becoming too great. In retreat, too, having two ropes of 150 feet enables long sections to be descended with ease, provided a sound anchor point is found. A rope longer than 150 feet becomes unmanageable, or the friction through the snap-links usually becomes too great after a certain distance.

By mid-afternoon, taking it in turns, we had run out the rope only nine times. Not much more than 1,000 feet, given that some of the rope was taken up with the knots tying the rope to our waists and to the pitons or other anchor points used to fasten one of us to the side of the mountain whilst the other was leading. There is 10,000 feet of climbing on this wall – 6,000 feet – more than a mile – in height. The route follows the lines of weakness, avoiding overhanging sections where possible, thus almost doubling the distance to be covered. Nearly two miles upwards on hands and knees. In one day we had barely done one-tenth, and the major difficulties were still to come. It was dark by 4.30 p.m. so we had to have chosen our bivouac site for the night before then. There were no natural ledges, all was concealed by the blanket of snow. Dick traversed to the left, towards a feature called the Shattered Pillar, but there was nowhere there to rest. We set to digging out a ledge in the snow...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.10.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-906148-75-9 / 1906148759 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-906148-75-1 / 9781906148751 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich