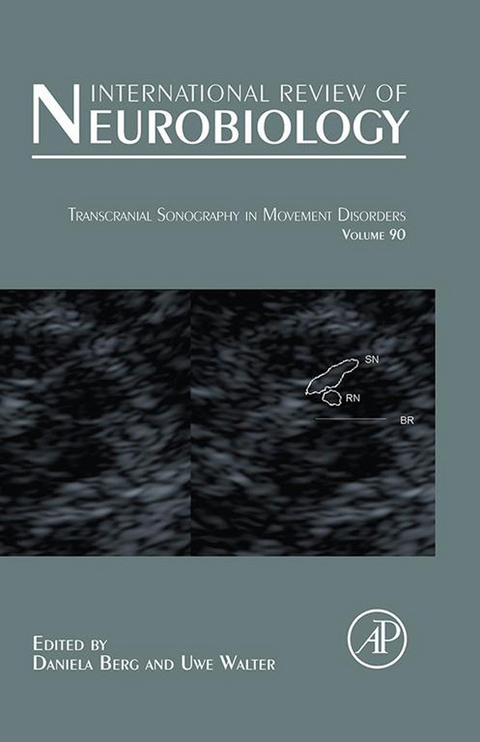

Transcranial Sonography in Movement Disorders (eBook)

320 Seiten

Elsevier Science (Verlag)

978-0-12-381331-2 (ISBN)

Transcranial Sonography in Movement Disorders

Cover 1

International Review of Neurobiology 2

Copyright 5

Contents 6

Contributors 12

Preface 14

Part I. Introduction 16

Introductory Remarks on the History andCurrent Applications of TCS 18

References 19

Method and Validity of Transcranial Sonography inMovement Disorders 22

I. Introduction 23

II. History of TCS in Movement Disorders 25

III. Technical Equipment and System Settings 26

IV. TCS Image Resolution 27

V. Procedure of Standard TCS Examination in Movement Disorders 30

VI. Transtemporal Investigation 32

VII. Transfrontal Investigation 41

VIII. Causes of Hyperechogenicity of Deep Brain Structures 41

IX. Limitations of TCS in Movement Disorders 42

X. Validity and Reproducibility of TCS in Movement Disorders 44

XI. Conclusions 45

References 45

Transcranial Sonography—Anatomy 50

I. Three Standardized Planes 50

II. Measurements and typical pathological findings 55

Part II. Transcranial Sonography in Relation in Parkinson's Disease 62

Transcranial Sonography in Relation to SPECT and MIBG 64

I. Introduction 65

II. Dopamine Transporter-SPECT in Parkinson’s Disease 66

III. Transcranial Sonography and DAT-SPECT in Parkinson’s Disease 67

IV. [123I]MIBG Myocardial Scintigraphy in Parkinson’s Disease 68

V. Transcranial Sonography and [123I]MIBG Cardiac Scintigraphy 70

VI. Transcranial Sonography of Substantia Nigra: Toward the FutureDevelopment of Early or Preclinical Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease 72

VII. Conclusion 74

References 74

Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease—TranscranialSonography in Relation to MRI 78

I. Introduction 78

II. Neuroimaging with TCS and Conventional MRI Techniques 79

III. MRI Studies of the Substantia Nigra in Parkinson’s Disease 81

IV. Structural Changes of the Substantia Nigra Revealed by MRI 82

V. Morphological and Biochemical Alterations of SN Assessed by TCSand MRI 85

VI. Correlation of MRI and TCS Findings of Substantia Nigra 88

References. 90

Early Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease 96

I. Difficulties in the Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease 97

II. Perspectives for Early Diagnosis of PD 104

References 105

Transcranial Sonography in the Premotor Diagnosis ofParkinson’s Disease 108

I. Introduction 108

II. Prevalence of SNþ in Healthy Controls 109

III. Association of SNþ with Putative Premotor Symptoms of PD 110

IV. [18Fluoro] Dopa-PET in SNþ Healthy Controls 116

V. Longitudinal Clinical Follow-Up Studies 117

VI. Conclusion 118

References. 118

Pathophysiology of Transcranial Sonography SignalChanges in the Human Substantia Nigra 122

I. Does Hyperechogenicity Reflect Death of Substantia NigraDopaminergic Neurons? 123

II. Does Hyperechogenicity Reflect a Low Substantia Nigra Cell Number? 126

III. Does Hyperechogenicity Reflect a Change in Nigra Volume or TissueComposition? 127

IV. Does Hyperechogenicity Reflect a Change in Iron in the SubstantiaNigra? Evidence from Animal Models and HumanPostmortem Studies 128

V. Does Hyperechogenicity Reflect a Change in Iron in the SubstantiaNigra? Evidence from Imaging Studies 130

References 132

Transcranial Sonography for the Discrimination of IdiopathicParkinson’s Disease from the Atypical Parkinsonian Syndromes 136

I. Introduction 137

II. Diagnostic Criteria of Atypical Parkinsonism 138

III. Systematic Review of the Literature on TCS and Parkinsonism 144

IV. Discussion 156

V. Conclusion 158

VI. Acknowledgments 159

References 159

Transcranial Sonography in the Discrimination ofParkinson’s Disease Versus Vascular Parkinsonism 162

I. Introduction 162

II. Vascular parkinsonism 163

III. TCS in the Differential Diagnosis of VP and PD 166

IV. Conclusion 169

References 170

TCS in Monogenic Forms of Parkinson’s Disease 172

I. Introduction 172

II. Substantia Nigra Hyperechogenicity in First-Degree Relatives ofSporadic PD Patients 174

III. Substantia Nigra Hyperechogenicity in Monogenic Forms of PD 174

IV. Conclusions and Future Perspectives 177

References 178

Par III. Transcranial Sonography in other Movement Disorders and Depression 180

Transcranial Sonography in Brain Disorders with TraceMetal Accumulation 182

I. Introduction 182

II. Substantia Nigra Echogenicity and Iron Metabolism 183

III. Lenticular Nucleus Hyperechogenicity and Iron Accumulation 186

IV. Lenticular Nucleus Hyperechogenicity and Copper Accumulation 186

V. Lenticular Nucleus Hyperechogenicity and Manganese Accumulation 188

VI. Conclusion 189

References 189

Transcranial Sonography in Dystonia 194

I. Introduction 194

II. Pathophysiology 195

III. Neuroimaging in Dystonia 196

IV. TCS in Primary Dystonia 196

V. TCS in Secondary Dystonia 197

VI. TCS in Patients with Herniated Cervical Disk 199

VII. TCS in Dystonia and Deep Brain Stimulation 199

VIII. Possible Causes of Hyperechogenicity of the LN in Dystonia 199

IX. Conclusions 200

References 201

Transcranial Sonography in Essential Tremor 204

I. Introduction—Essential Tremor as a Diagnostic Challenge 205

II. Transcranial Sonography in the Differential Diagnosis of ET and PD 206

III. Conclusion 208

References 211

Transcranial Sonography in Restless Legs Syndrome 214

I. Restless Legs Syndrome 214

II. From Parkinson’s Disease to RLS 215

III. Sonography of the Substantia Nigra in RLS 216

IV. Sonography of Other Structures in RLS 224

V. Special Instructions for TCS in RLS 226

VI. Summary 228

References 228

Transcranial Sonography in Ataxia 232

I. Introduction 233

II. Method of Transcranial Sonography in Ataxia 235

III. TCS in Spinocerebellar Ataxia 237

IV. TCS in other Neurological Disorders with Ataxia 244

V. Conclusions and Future Perspectives 246

References 247

Transcranial Sonography in Huntington’s Disease 252

I. Introduction 253

II. Method of Transcranial Sonography in Huntington’s Disease 257

III. Frequency of Abnormal TCS Findings in HD 259

IV. TCS Findings Related to Motor Features in HD 262

V. TCS Findings Related to Cognitive Features in HD 265

VI. TCS Findings Related to Psychiatric Features in HD 266

VII. Conclusions and Future Perspectives 268

References 268

Transcranial Sonography in Depression 274

I. Transcranial Sonography in Depression—First Findings andImplications 274

II. Method of Transcranial Sonography in Depressive Disorders 275

III. TCS Findings in Unipolar Depression and Depression Associated withNeurodegenerative Diseases and other Etiologies 276

IV. The Concept of the Basal Limbic System in Depression 281

V. MRI Studies Supporting TCS Findings and the Concept of the BasalLimbic System 282

VI. Postmortem Studies 284

VII. Conclusions and Further Perspectives 284

References 285

Part IV. Future Applications and Conclusion 288

Transcranial Sonography-Assisted Stereotaxy and Follow-Up ofDeep Brain Implants in Patients with Movement Disorders 290

I. Introduction 290

II. Advances in TCS Image Resolution 291

III. Technical and Safety Issues Concerning TCS of Brain Implants 292

IV. TCS for Intraoperative Optimization of Implant Placement 293

V. TCS for Postoperative Position Control of Deep Brain Implants 296

VI. Current Limitations and Future Issues 297

References 299

Conclusions 302

I. General Remarks 302

II. Personal Remarks 304

Index 306

Contents of Recent Volumes 316

Transcranial Sonography—Anatomy

Heiko Huber Department of Neurodegeneration, Hertie Institute of Clinical Brain Research and German Center of Neurodegnerative Diseases (DZNE), Tübingen, Germany

Abstract

Transcranial B-Mode sonography (TCS) allows quick, reliable, and inexpensive depiction of a number of brain structures, which may help in the diagnosis and differentiation of various movement disorders. In the following sections the anatomical structures in three standardized TCS planes (Section I) and the methods of measurement and typical pathological findings in specific structures (Section II) will be described. For better orientation, TCS images are complemented by compatible MRI images.

Keywords

Anatomy

transcranial sonography

Mesencephalic Brainstem

Third Ventricle

Ventricular System

Lentiform Nucleus

Substantia Nigra

Raphe

I Three Standardized Planes

For the investigation of patients with movement disorders, it is important to know three standardized planes of B-Mode sonography.

The investigation is started by placing the ultrasound probe at the middle or the posterior temporal acoustic bone window (Fig. 1) in parallel to the imagined orbito-meatal line (Fig. 1, OM). By doing so, one usually visualizes the plane of the mesencephalic brainstem (Fig. 1, A1). By tilting the probe slightly upward for about 10–20˚ the ventricular plane is reached (Fig. 1, A2). These are the two standard planes for routine TCS in a movement disorder patient. In previous papers, the cella media plane has been mentioned as well. However, this does not contribute to the evaluation of movement disorders––therefore, this plane will not be commented upon in this chapter. However, in addition to the two axial planes, the plane of the cerebellum (Fig. 1, A3) can be assessed in a standardized fashion by rotating the ultrasound probe for about 30–45˚ to visualize the posterior fossa.

A The Plane of the Mesencephalic Brainstem

The mesencephalic brainstem plane constitutes a nearly axial section through the midbrain. As shown in Fig. 2, the key structure within this plane is the butterfly-shaped midbrain, which is hypoechogenic contrasting the strongly echogenic basal cisterns. In comparison to the standard MRI images, TCS allows to differentiate a number of different structures within the midbrain, i.e., substantia nigra (SN), red nucleus (RN), brainstem midline raphe (BR), and aqueduct. Abnormalities in these midbrain structures have shown to be valuable markers for a variety of disorders, including idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, restless legs syndrome, and major depression.

In addition to the midbrain structures, also other structures, including vessels in the basal cisterns, the hippocampus, the lower frontal lobe, parts of the temporal and occipital lobes as well as the upper and medial parts of the cerebellum, can be clearly distinguished within this plane.

B The Plane of the Third Ventricle

The plane of the third ventricle is reached by tilting the ultrasound probe slightly 10–20˚ upward starting from the midbrain plane. As shown in Fig. 3, this mild angulation of the probe results in a cross section through the brain, which is not compatible to the axial MRI slices and does not allow direct comparison of the left and right sides. Because of the wavelengths used to penetrate the skull, resolution close to the probe is only limited. Therefore, only structures close to the midline (e.g., the third ventricle) are evaluated at the side ispilateral to the insonating probe while structures more distant from the midline (like the basal ganglia) are generally evaluated from the contralateral side (see below). Landmark structure for orientation in this plane is the pineal gland, which normally appears strongly hyperechogenic due to calcification and is located adjacent to the posterior surface of the third ventricle. This plane allows assessment of the ventricular system including not only the third ventricle, but also the anterior and posterior horns of the lateral ventricles. Measurement of the third ventricle has been shown to be valid and reliable and correlates well with the findings of other structural neuroimaging methods (Berg et al., 2000). Normal values for the width of the ventricular system have been published (Seidel et al., 1995). From this and other studies, age-related normal values have been derived, which should be referred to when the diagnosis of an enlargement of the ventricular system due to brain atrophy, hydrocephalus, etc. is made (see Table I). Moreover, the thalamus and the basal ganglia including lentiform and caudate nuclei can be assessed. Normally, these structures appear isoechogenic compared to the surrounding tissue. In some cases, however, hyperechogenic areas may occur at the anatomical site of these structures, which is abnormal and related either to a pathological condition or to an abnormality without clear clinical implications, such as slight calcification of the basal ganglia.

Table I

Normal Values of the Ventricular System

| Age | 2nd ventricle | 3rd ventricle |

| <60 years | <17 mm | <7 mm |

| >60 years | <20 mm | <10 mm |

Values from 49 healthy volunteers as sum scores ± 1 standard deviation (See also Berg et al., 2008).

C Plane of the Posterior Fossa

The posterior fossa can be visualized by rotating the anterior pole of the probe upward for about 45˚ starting from the imagined orbitomeatal line (compare Fig. 1). This plane also does not correspond to the common axial or coronal MRI slices (Fig. 4). It allows assessment of the fourth ventricle as well as of the cerebellar hemispheres, the vermis, and especially the dentate nucleus, which can sometimes be found to be slightly hyperechogenic compared to the surrounding tissue. Other structures that can be pictured in this plane, such as the brainstem, the hippocampus, or the cerebral lobes, are better assessed in one of the other planes and have not been evaluated so far in this plane. The plane of the posterior fossa does not belong to the routine workup so far, and proper depiction of structures in this plane is more dependent on the quality of the temporal acoustic bone windows. Therefore, data on the pathophysiological findings in this plane are limited and standardization of assessments in this plane is still in progress.

II Measurements and typical pathological findings

Well examined and of special interest to the evaluation of patients with movement disorders are the ventricles, the lentiform nucleus, the substantia nigra, and the mesencephalic midline raphe. The methods for quantitative assessment and examples of typical pathological findings for these specific structures are shown below.

A Ventricular System

The width of the third ventricle and the anterior horn of the contralateral lateral ventricle of the ventricular system must be measured in a regular exam. Especially, the width of the third ventricle has been shown to correlate well with the measurements on CT scans. Both structures are best visualized in the third ventricular plane (compare IB). For assessment of the third ventricle, the largest distance between the inner surfaces of both ependymal linings is measured perpendicularly in the frozen and about a twofold magnified image. In the same plane, the contralateral anterior horn is evaluated by using the midline as orientation. The distance between the medial (nearest to the midline) to the lateral ependymal lining (farthest from the midline)—again perpendicularly from the midline—is used for measurement of the anterior horn. Figure 5B shows a case of a pathologically enlarged ventricular system.

The posterior horn is in general not measured (there exist no standard values so far); however, the impression of an enlarged posterior horn should be documented.

B Lentiform Nucleus

The lentiform nucleus (LN) is also visualized in the third ventricular plane. Regularly, it is isoechogenic to the surrounding tissue and therefore cannot be quantitatively assessed. Hence, usually a semi-quantitative rating applying a three-item scale is used, rating “normal LN echogenicity,” “moderate LN hyperechogenicity,” and “marked LN hyperechogenicity.” Moderate LN hyperechogenicity...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.9.2010 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Neurologie |

| Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Radiologie / Bildgebende Verfahren ► Sonographie / Echokardiographie | |

| Studium ► 2. Studienabschnitt (Klinik) ► Pathologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie | |

| Technik | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-12-381331-X / 012381331X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-12-381331-2 / 9780123813312 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich