With recent advances of modern medicine more people reach the 'elderly age' around the globe and the number of dementia cases are ever increasing. This book is about various aspects of dementia and provides its readers with a wide range of thought-provoking sub-topics in the field of dementia. The ultimate goal of this monograph is to stimulate other physicians' and neuroscientists' interest to carry out more research projects into pathogenesis of this devastating group of diseases.

Cover 1

International Review of Neurobiology 2

Copyright 5

Contents 6

Contributors 10

Preface 12

Underlying Brain Mechanisms that RegulateSleep–Wakefulness Cycles 14

I. Wakefulness-Regulating Systems 15

II. Sleep-Regulating Neurons in the Preoptic Hypothalamus 18

III. Homeostatic Regulation of Arousal States and Preoptic SleepRegulatory Systems: Recent Findings 21

IV. Integration of Sleep-Regulatory Neuronal Activity in the Preoptic Area 24

V. Descending Modulation of Arousal Systems by Sleep-RegulatoryNeurons in the Preoptic Area 26

Acknowledgments 28

References 29

Changes In EEG Pre and Post Awakening 36

I. Introduction 37

II. EEG Changes Preceding an Awakening 40

III. EEG Changes Following an Awakening 57

IV. Summary 61

References 63

What Keeps Us Awake?—the Role of Clocks and Hourglasses,Light, and Melatonin 70

I. Introduction 71

II. Circadian and Homeostatic Impetus for Wakefulness 73

III. Effects of Light on Human Wakefulness 80

IV. Effects of Melatonin on Human Sleep and Wakefulness 90

References 96

Suprachiasmatic Nucleus and Autonomic Nervous SystemInfluences on Awakening From Sleep 104

I. Introduction 104

II. SCN Output Rhythms 106

III. The Cortisol/Corticosterone Awakening Rise 107

IV. The Dawn Phenomenon 110

V. The Awakening of the Cardiovascular System 113

VI. Conclusion 115

Acknowledgments 115

References 115

Preparation for Awakening: Self-Awakening Vs. ForcedAwakening: Preparatory Changes inthe Pre-Awakening Period 122

I. Introduction 123

II. Definitions 123

III. Effects of Attempt to Self-Awaken on Sleep 124

IV. Self-Awakening and Daytime Functions 127

V. Habit and Ability of Self-Awakening 128

VI. Factors of Successful Self-Awakening 132

VII. Schematic Model of Self-Awakening 136

VIII. Conclusion 138

References 138

Circadian and Sleep Episode Duration Influences on Cognitive PerformanceFollowing the Process of Awakening 142

I. Introduction 143

II. Time-of-Day and Cognition 143

III. Time-of-Day Effects and Waking Up 146

IV. Length of Sleep Episode and SI 150

V. Different Measures of Cognitive Functioning 155

References 159

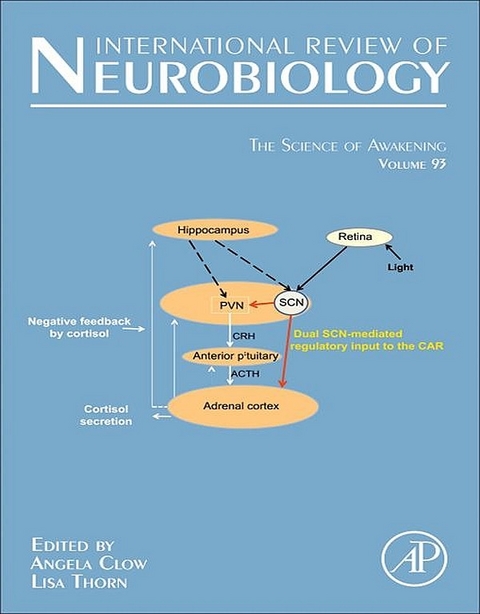

The Cortisol Awakening Response in Context 166

I. Introduction 166

II. History of the Investigation of the CAR 168

III. Distinct Regulation of the CAR and Relationship with the SCN 172

IV. The CAR as an Awakening Process 174

V. CAR and Cognitive Awakening 175

VI. CAR and Immunological Awakening 177

VII. CAR and Behavioral Awakening 178

VIII. Measurement of the CAR 179

IX. Conclusions 182

References 183

Causes and Correlates of Frequent Night Awakeningsin Early Childhood 190

I. Parenting Practices 192

II. Family Context 196

III. Child Characteristics 198

IV. Summary 200

References 201

Pathologies of Awakenings: The Clinical Problem of InsomniaConsidered From Multiple Theory Levels 206

I. Chronic Insomnia: Syndromes of Pathological Awakenings 207

II. Background Conceptual Features of Analysis of Realities About Sleep 213

III. The Spielman three-factor High-Level Model of Insomnia and Mid-Level Therapeutic Theories of Insomnia Therapies 218

IV. Cautions About Conceptual Transitions to the Theory Levelof Neuronal Processes 222

V. An Aristotelian Method of Review 223

VI. Conclusion 236

References 237

The Neurochemistry of Awakening: Findings from SleepDisorder Narcolepsy 242

I. Introduction 243

II. Neurobiology of Wakefulness 244

III. Narcolepsy and Symptoms of Narcolepsy 245

IV. Discovery of Hypocretin Deficiency and Postnatal Cell Deathof Hypocretin Neurons 247

V. Idiopathic Hypersomnia, Hypocretin Non-deficient PrimaryHypersomnia 250

VI. Symptomatic Narcolepsy and Hypersomnia: Hypocretin Involvements 252

VII. How Does Hypocretin Ligand Deficiency Cause the NarcolepsyPhenotype? 256

VIII. Considerations for the Pathophysiology of Narcolepsy with NormalHypocretin Levels 258

IX. Changes in Other Neurotransmitter Systems in Narcolepsyand Idiopathic Hypersomnia 259

X. Involvements of Histaminergic Neurotransmission in HumanNarcolepsy and Other Hypersomnia 261

XI. Conclusion 263

Acknowledgments 264

References 264

Index 270

Contents of Recent Volumes 278

Underlying Brain Mechanisms that Regulate Sleep–Wakefulness Cycles

Irma Gvilia*,†,‡ * Ilia State University, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia

† Research Service, Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, North Hills, CA 91343, USA

‡ Department of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA

Abstract

Daily cycles of wakefulness and sleep are regulated by coordinated interactions between wakefulness- and sleep-regulating neural circuitry. Wakefulness is associated with neuronal activity in cholinergic neurons in the brainstem and basal forebrain, monoaminergic neurons in the brainstem and posterior hypothalamus, and hypocretin (orexin) neurons in the lateral hypothalamus that act in a coordinated manner to stimulate cortical activation on the one hand and behavioral arousal on the other hand. Each of these neuronal groups subserves distinct aspects of wakefulness-related functions of the brain. Normal transitions from wakefulness to sleep involve sleep-related inhibition and/or disfacilitation of the multiple arousal systems. The cell groups that shut off the network of arousal systems, at sleep onset, occur with high density in the ventral lateral preoptic area (VLPO) and the median preoptic nucleus (MnPN) of the hypothalamus. Preoptic neurons are activated during sleep and exhibit sleep–wake state-dependent discharge patterns that are reciprocal of that observed in several arousal systems. Neurons in the VLPO contain the inhibitory neuromodulator, galanin, and the inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). The majority of MnPN sleep-active neurons synthesize GABA. VLPO and MnPN neurons are sources of projections to arousal-regulatory systems in the posterior and lateral hypothalamus and the rostral brainstem. Mechanisms of sleep induction by these nuclei are hypothesized to involve GABA-mediated inhibition of multiple arousal systems. Normal cycling between discrete behavioral states is mediated by the combined influence of a sleep need that increases with continued wakefulness and an intrinsic circadian oscillation. This chapter will review anatomical and functional properties of populations of sleep- /wake-regulating neurons, focusing on recent findings supporting functional significance of the VLPO and MnPN in the regulation of sleep–wake homeostasis. Evidence indicating that MnPN and VLPO neurons have different, but complementary sleep regulatory functions will be summarized. Potential mechanisms that function to couple activity in these two sleep-regulatory neurons will be discussed.

Keywords

Sleep regulation

Sleep-wakefulness cycle

Preoptic hypothalamus

Sleep homeostasis

I Wakefulness-Regulating Systems

Wakefulness is generated by multiple neuronal systems extending from the brainstem reticular formation to the thalamus and through the posterior hypothalamus up to the basal forebrain. These neuronal systems, including cholinergic neurons in the brainstem and basal forebrain, monoaminergic neurons in the rostral pons, midbrain and posterior hypothalamus, and hypocretin-(orexin)-containing neurons in the perifornical lateral hypothalamus, impart a tonic background level of activity that is crucial for cortical activation on the one hand and behavioral arousal on the other hand. Each of these neuronal groups subserves distinct aspects of wakefulness-related functions of the brain.

In 1935, Bremer (1935) demonstrated that transection of the brainstem at the pontomesencephalic level (but not the spinomedullary junction) produced coma in anesthetized cats. This finding provided evidence of an “ascending arousal system” necessary for forebrain and cortical arousal. More than a decade later, Morruzzi and Magoun (1949) provided additional support for the concept of an ascending arousal system when they showed that electrical stimulation of the rostral pontine reticular formation produced a desynchronized electroencephalogram (EEG) in anesthetized cats. These findings challenged the prevailing view that wakefulness-related activity of the brain and consciousness were dependent upon sensory stimulation and eventually led to the concept that wakefulness requires critical levels of ascending activation originating in the brainstem reticular formation (Moruzzi and Magoun, 1949; Starzl et al., 1951).

Reticular formation, a diffuse system of nerve cell bodies and fibers in the brainstem, extends from the medulla oblongata to the thalamus and sends nonspecific impulses throughout the cortex to “awaken” the entire brain. In addition, brainstem reticular neurons project into the hypothalamus and basal forebrain where neurons are located that also project to the cerebral cortex and participate in the maintenance of an “alert” cerebral cortex. Neurons in the medullary and caudal pontine reticular formation are particularly important for maintaining postural muscle tone along with behavioral arousal via their descending projections to the spinal cord. Neurons in the oral pontine and midbrain reticular formation are essential for sustaining cortical activation, characterized by the low-voltage, high-frequency cortical EEG patterns. Large lesions of the rostral brainstem reticular formation result in a loss of cortical activation and a state of coma in animals and humans. Electrical stimulation of the reticular formation elicits fast cortical activity and waking. Neurons of the pontomesencephalic reticular formation discharge at high rates during waking in association with fast cortical activity, and they give rise to ascending projections by which they excite the forebrain and thus comprise what Moruzzi and Magoun called the “ascending reticular activating system.”

Studies in the 1970s and 1980s revealed that the origin of the ascending reticular activating system was not a neurochemically homogenous mass of reticular tissue in the brainstem tegmentum, but rather is comprised of a serious of well-defined cell groups with identified neurotransmitters (Saper et al., 2001, 2005). As mentioned above, these systems produce cortical arousal via two pathways: a dorsal route through the thalamus and a ventral route through the hypothalamus and basal forebrain. A key component of the dorsal branch of the ascending arousal system, which provides a major excitatory signal from the upper brainstem to the thalamus, is the cholinergic neurons in the pedunculopontine (PPT) and laterodorsal (LDT) tegmental nuclei utilizing acetylcholine, an excitatory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system (Hallanger et al., 1987; Levey et al., 1987; Rye et al., 1987). These cell groups activate the thalamic relay neurons that are crucial for transmission of information to the cerebral cortex and the reticular nucleus of the thalamus acting as a gating mechanism in providing signal transmission between the thalamus and the cerebral cortex (McCormick, 1989). The neurons in the PPT and LDT fire most rapidly during wakefulness and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, a state characterized by cortical activation (Strecker et al., 2000). These cells are much less active during nonREM sleep, when cortical activity is slow. In this view, the thalamus is thought to function as a major relay to the cortex for the ascending arousal system with the overall activity of the thalamo-cortical system forming the origin of the cortical EEG. Indeed, thalamic relay neurons fire in patterns that correlate with cortical EEG (Steriade et al., 1993). In turn, the overall activity in the thalamo-cortical system is thought to be regulated by the ascending arousal system.

Another population of cholinergic neurons is intermixed with noncholinergic (largely GABAergic) neurons in the basal forebrain (including the nucleus basalis and magnocellular preoptic nucleus in the substantia innominata and the medial septal nucleus and nucleus of the diagonal band of Broca) that project to the cortex, hippocampus, and to a lesser extent, the thalamus. The basal forebrain cholinergic neurons are also implicated in behavioral arousal and EEG desynchronization (Berridge and Foote, 1996; Lee et al., 2005; Saper, 1984). The cholinergic basal forebrain neurons discharge at high rates in association with cortical activation during waking and REM sleep (Lee et al., 2004), whereas inhibition of these neurons can slow the EEG. Acetylcholine released in the cortex excites cortical neurons so that they discharge at high frequencies subtending cortical fast EEG activity. Lesions of the basal forebrain result in severe deficits in waking and a state of coma (Buzsaki et al., 1988).

Other functionally important arousal regulatory cell group is monoaminergic neurons in the upper brainstem and caudal hypothalamus, including the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (LC) (Jones and Yang, 1985; Loughlin et al., 1982), the serotonergic dorsal (DR) and median raphe nuclei (Sobel and Corbett, 1984; Tillet, 1992; Vertes, 1991), the dopaminergic neurons in the ventral periaqueductal grey matter, and histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) (Lin et al., 1988, 1994; Takeda et al., 1984). Monoaminergic cell groups project to the intralaminar and midline thalamic nuclei and also innervate...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.11.2010 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Medizin / Pharmazie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Neurologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Humanbiologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Zoologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-12-381325-5 / 0123813255 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-12-381325-1 / 9780123813251 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,8 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: PDF (Portable Document Format)

Mit einem festen Seitenlayout eignet sich die PDF besonders für Fachbücher mit Spalten, Tabellen und Abbildungen. Eine PDF kann auf fast allen Geräten angezeigt werden, ist aber für kleine Displays (Smartphone, eReader) nur eingeschränkt geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Zusätzliches Feature: Online Lesen

Dieses eBook können Sie zusätzlich zum Download auch online im Webbrowser lesen.

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Größe: 9,6 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Zusätzliches Feature: Online Lesen

Dieses eBook können Sie zusätzlich zum Download auch online im Webbrowser lesen.

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich