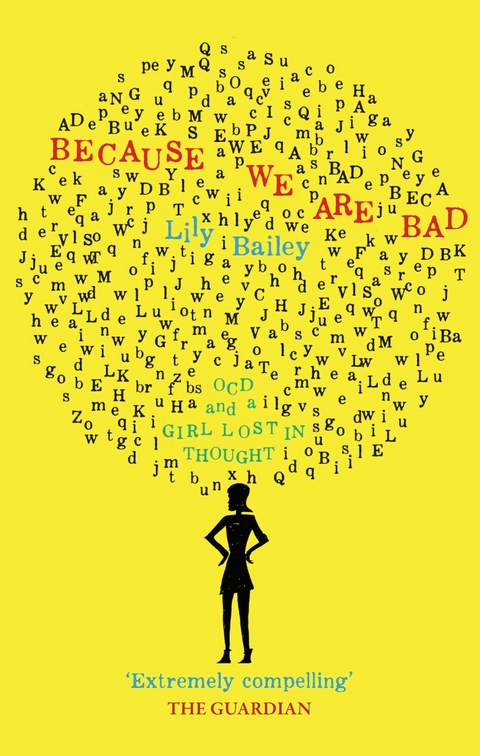

Because We Are Bad (eBook)

256 Seiten

Canbury (Verlag)

978-0-9930407-3-3 (ISBN)

Lily Bailey is a model and writer. She became a journalist in London in 2012, editing a news site and writing features and fashion articles for local publications including the Richmond Magazine and the Kingston Magazine. As a child and teenager, Lily suffered from severe Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). She kept her illness private, until the widespread misunderstanding of the disorder spurred her into action. In 2014 she began campaigning for better awareness and understanding of OCD, and has tried to stop companies making products that trivialise the illness. Her first book, Because We Are Bad (Canbury Press), published in May 2016, reveals her experience of OCD. She lives in London with her dog, Rocky.

Lily Bailey is a model, writer, and mental health campaigner. As a child and teenager, Lily suffered from severe Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). She kept her illness private, until the widespread misunderstanding of the disorder spurred her into action. She began campaigning for better awareness and understanding of OCD, and has tried to stop companies making products that trivialise the illness. Her first book, BECAUSE WE ARE BAD (Canbury Press, 2016) chronicles her personal experience of OCD as a child and a young woman. Her second book, WHEN I SEE BLUE (Orion, 2022), is aimed at children and follows a 12-year-old boy who has OCD.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. CHESBURY HOSPITAL. Lily Bailey is in Chesbury Hospital, a private facility in London for patients with mental and physical illnesses. Lily is 19. 'The observation room is next to the nurses' station; they keep you there until you are no longer a risk to yourself.'

2. MY FRIEND. Lily is in the playground, but her imaginary friend is not the others. She lives in her head all the time. 'Two of us sat side by side in my head, woven together, inseparable. She didn't even have a name; she was just She. Really, it was hard to say where She ended and I began.'

3. THE LETTER. Lily gets a letter from school, which must contain terrible news. Lily hides the letter from her grandmother because this terrible news must not reach her father and mother. Lily is bad. Very bad. Her cousin has died: Lily killed him with a thought.

4. NEW SCHOOL. It is Lily's first day at Buxton House. The other children laugh at Lily. She repeats the words: 'Fresh start. Fresh start. Fresh start.' Lily creeps into her sister's room because Ella could stop breathing at any moment. It is important to check that Ella is alive.

5. MUM AND DAD. Lily is told to be concerned with hygiene when visiting the swimming pool. Lily resolves to take this very seriously. Her routines intensify. Intrusive thoughts pop into her head. Mum and Dad's arguing worsens.

6. SWEARING IN CHURCH. 'Church is not the place for these words, but we can't make them go away. Fucking boring ass church. Crap, fuck, shit, wanker, cunt.' Lily is one of the best at maths, but when Lily makes a mistake her friend in her head says: 'Stupid. Stupid. Stupid'.

7. MOST APOLOGETIC GIRL. At the Buxton House Leavers' Awards, Lily receives an unusual award. 'I'm sorry I was laughing when you walked past me in the corridor yesterday. I want you to know it was about something Mia said. I wasn't laughing at you.'

8. HAMBLEDON. When she moves to boarding school, Lily's routines intensify. 'Recording our mistakes has become our full-time occupation. Most words are generated when interacting with other people, like at mealtimes or when everyone is hanging out in the dorm.' She lists her errors for 4 hours a day.

9. RUNNING FROM WORDS. Lily takes up athletics to flee from the lists that form in her heads. If she can run fast enough, the exertion - the sheer breathlessness - will silence her mind.

10. STUMBLING. Unable to keep up with her routines and overwhelmed with her lists, Lily's world finally collapses. She rushed to the bathroom. 'We curl up in a ball and rock back and forward. Normally the cold tiles make us feel better, but today they don't'

11. SPECIAL NEEDS DEPARTMENT. Lily has to take GCSEs and is awarded 'extra time' because she is a 'slow processor'. Her friend in her head takes issue with the extra time Lily has been given. She scolds her: 'Lying scummy cheat. Lying scummy cheat. Lying scummy cheat.'

12. COMING HOME. Lily feigns an illness so that she is discharged from school. Her mother picks her up and takes her to a homeopathic doctor who prescribes some pills. Her mother also takes Lily to a GP, who finds her iron is low. She is referred to a specialist

13. DOCTOR, DOCTOR. At a psychiatric hospital, Lily meets Dr Finch for the first time. Her friend insists there is no need to see this doctor. Has she ever let her down? Dr Finch says Lily has OCD: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Her friend is unhappy. 'OCD is a mental disorder. What we do is good'

14. PILLS, PILLS, PILLS. Having an invisible friend is unusual in OCD, Dr Finch explains. She says that Lily is not a bad person, but is worried about being a bad person. Lily must do CBT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. She tells Lily to rest from her routines. Lily's friend is unhappy and mocks her.

15. DRIVING. Lily goes on a car journey with Dr Finch. Lily's friend is protesting, whining. Dr Funch says: 'You know who your "friend" reminds me of? A wife beater.

20

Mental Ward

I’ve been transferred from intensive care to the psychiatric unit. It’s a state place, and the rumours are true: it feels like a scrapyard for brains.

I’m in a room with four other people. The woman opposite me is screaming that the nurses are monsters and the doctors are devils pretending to be gods and even the orderlies are demons. Someone has given her flowers, but she has thrown them and now they are lying dead like soldiers on a linoleum battlefield.

Next to me is a nice middle-aged woman who keeps repeating the same things and forgetting what she said five minutes ago. She has asked me my age four times. Four times I have told her: 19. She can’t stop dribbling; the front of her sweater is drenched. She tells me I am pretty over and over. She says I don’t look crazy, and that I am too young to have troubles. She asks me if I have ‘the anorexia.’

On the far side of the room is probably the ugliest woman I’ve ever seen. She is sweaty and vast, with wrinkles that look like they’ve been chiseled in by a drill. She has been staring at me and farting for the last half an hour. She sits on her bed in a hospital gown, with her legs crossed. She isn’t wearing any underwear. A nurse keeps pulling down her gown and talking about ‘modesty,’ but it’s no good, it just rises back up. I try not to see the thick bush and saggy pink folds of skin, but I already have done. I am a PERVERT.

I can’t believe I’m not dead.

The most effective method would be to throw myself in front of a car or train, but I don’t want to ruin someone else’s life too. I need to jump off something, and make sure I don’t land on anyone. I need to get to the top of the hospital. The windows may be locked, but that’s okay. I can smash one. I get out of bed. I walk down the corridor to the end of the ward, where I encounter two security guards in front of a coded door.

‘What do you think you’re doing, girlie? This is a high-security ward. You don’t just leave. Go back to your room.’

Deirdre and Nessa visit. They have brought me clothes, a wash bag, and a book.

‘We brought you Peter Pan,’ says Deirdre, handing me my tatty blue copy.

‘I know it’s your favourite.’

I flick through the pages, staring at the black-and-white illustrations I used to trace with my finger when I was small.

They are kind to me. They don’t judge. They stay with me, sitting on the end of my bed. I am grateful they are here, but panicking—because words are arriving on my list thick and fast, and without a pen and paper to write them down, I feel stranded.

‘You scared us, Lily. I mean, you really, really scared us,’ Nessa says.

‘We called your parents. We had to,’ says Deirdre. ‘They’re on their way.’

The psychiatrist is about 50, with a grey mop of hair. He wears shabby brown trousers and a shabbier shirt.

We talk for half an hour. He seems friendly enough. He asks me what drove me to the edge. His voice is lilting, firm but soft at the same time.

‘I’m a bad person. I spend my life trying to be good, and it’s never enough.’

‘Is there anything else?’

‘I love my doctor. I’m obsessed by her. It’s not an OCD thing. Actually, I think it is. Oh, I don’t know anymore.’

It shocks me that I have said these words out loud. I want to undo them; Command Z the air.

‘Mostly, I’m just a very, very bad person. I don’t deserve to exist.’

‘Do you know what I see?’

I shake my head.

‘I see an intelligent girl who has a decision to make. Are you going to pick yourself up and do something with that intelligence, or are you going to throw it all away because right now, at this point in time, you don’t feel like a good person? Anyway, I can’t see anything bad. I mean, sure, you’re English. But you can’t help that now, can you?’

Dad arrives that evening; he got the first flight from London. He strides onto the ward purposefully with a big bottle of Lucozade.

Then he crumples onto the end of my bed. He sits and asks ‘Why, why, why?’

‘I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know,’ I say.

He tries to persuade me to eat the fizzy snakes and jelly sweets he bought at the airport.

I don’t want them, but when he’s gone, I eat them all.

I am ravenous.

Mum arrives the next day. She has flown in from Thailand, where she was doing a four-week yoga course that I didn’t think about when I took the pills. She is tanned, but there’s no glow. Her eyes are full of tears. She tells me she is so glad I am not dead. So, so glad.

They take me for lunch at the hospital café. This is the first time in forever I’ve seen my parents at peace. There is a weird sense of camaraderie. They say things that make me laugh; they tell me they still love me.

I’m trying to focus, which is difficult because for the last 24 hours I’ve been storing the lists in my head instead of writing them down.

They tell me it’s time to go home. I thought I’d been sectioned, but they have persuaded the hospital that better treatment is available in the UK. While I was sleeping, Dad went to the police station and sorted out the mess, so I won’t have to attend a court date. He also spoke to the college, and apparently I’m not going to be in any trouble. Mum is going to help me get my things. I am so very lucky that I have parents who love me as much as mine.

Back on the ward, the dribbling woman comes over to my bed, speaking quickly, her face nearly touching mine.

‘If you’re going home, luvvie, can you do me a favour? I have family and I’m not allowed out. But I’m sure they’re going to visit me here this Christmas. Can you get them gifts? Anything you like; chocolate, perfume—the expensive stuff.’ She presses 40 euros into my palm. ‘Please? It would mean the world to me.’

I’m not sure what to do. Maybe this family isn’t coming, and the presents will sit by her bed, making her feel worse. Maybe she really needs these 40 euros; maybe this is not the right thing to spend them on. I look at Mum. She is nodding obligingly. I’m too tired to make decisions.

Half an hour later, Mum and I are back with perfume and chocolates and 10 euros change. I give the woman a box of chocolates I bought for her myself, because although I really hope her family does exist, they might not, and I want her to have a present. She starts crying and telling me I am beautiful, and that she hasn’t had a Christmas present in years. She is holding my hands in hers and asking why God has blessed her by allowing me into her life.

Then I tell her gently that I have to go. She nods.

‘I understand, dearie,’ she says. ‘This place isn’t for everyone.’

Mum and I get a taxi back to the dorm and start chucking things into bags at full speed, like looters: books, T-shirts, stationery, shoes, linen, towels, dresses, shampoo, posters. I take the unopened letter to Dr Finch out of the top drawer and place it carefully in my handbag. We haul everything into the hallway and lock the door.

Deirdre, Molly, and other girls from my corridor are hanging around outside, unsure of the appropriate etiquette to use.

‘Apparently you had appendicitis,’ says Molly. She looks hurt at being out of the loop. I know she knows. I piece things together. Deirdre and Nessa are the ones who know. Everyone else just know knows.

21

Harley Street

I’ve been home for a week, festering, writing endless lists. A notepad has become the new storage form. It has pros and cons, but I can’t risk losing my lists again by putting them on a new phone. Mum and Dad say it is important that Ella is not told the full extent of what happened. She was at boarding school when I got back, so she doesn’t know the circumstances of my arrival home. Mum lets her believe I’m just here for Christmas. She peeks into my room every couple of days, lingering uncertainly by the door and tugging her sweater sleeves down over her thumbs, asking if I want to ‘do something.’

‘No, no,’ I say.

Yesterday she crawled into bed with me, nuzzling up to my side like she used to when we were small. Her skin touched mine; my flesh sizzled. I saw my hands at her breast, though I knew they were clamped by my sides.

‘No, no!’ I said.

‘I don’t get it,’ she replied, lower lip wobbling. ‘I was so excited about you coming back, but you don’t want to see me. I feel like I’ve lost you.’

As for Mum, she has employed different approaches, and all in such rapid succession it’s like watching a camera whiz through a day in one location in the space of 20 seconds. Blue sky that is obliterated by foamy clouds charging in from the left, pink seeping in from the corners of the frame tells you the sun is setting, a bird soars across like a rocket, nighttime—a spray of stars, dawn, then back to blue . . .

She was patient at first. She asked me if I wanted to talk; she suggested going outside for walks; she tried to understand. But I kept telling her not to come in please and that I wanted to be alone.

When I didn’t change my tune, she became a stroppy teenager. She was textbook. I’d seen this act 1,000 times before from girls at Hambledon. ‘Okay, fine.’ She shrugged. ‘I just don’t think it’s good for you to be in your room all day. But whatever.’

Passive enough on the outside, sure. But fire within.

On Wednesday it rained love. ‘I love you so much, do you know how much I love you? Do you know that I would do anything in the world to make you better? And do you know how...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.5.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Gesundheitswesen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik ► Sozialpädagogik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Bryony Gordon • Career in journalism • Cognitive Behavioural Therapy • Contamination OCD • dawn o'porter • doing compulsions • eat drink run • eliminate negative thinking • English girls boarding school • GCSE Extra Time • Glorious Rock Bottom • hand washing OCD • Harley Street • Harley Street clinic • jog on • Lily Bailey • mad girl • Making lists in head • Mental Health • mental health memoir • Mental Illness • NHS • obsessive compulsive disorder • obsessive thoughts • obsessive thoughts book • OCD • OCD biography • ocd book • OCD book memoir • OCD experiences book • OCD memoir • OCD psychiatrist • OCD support group • OCD therapy • OCD workbook • psychiatric hospital • Pure Rose Cartwright • Relationship with psychiatrist • Resisting urine test • ruby wax • Sectioned OCD • Swearing in church • Thailand gap year • the ACT workbook for teens with OCD • The Man Who Couldn't Stop • The Priory • Trinity College • unwanted thoughts |

| ISBN-10 | 0-9930407-3-X / 099304073X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-9930407-3-3 / 9780993040733 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich