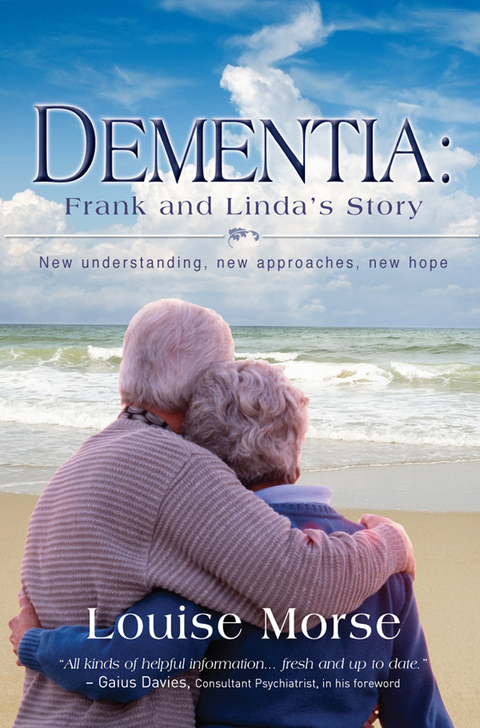

Dementia: Frank and Linda's Story (eBook)

256 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-85721-359-4 (ISBN)

This book describes how a new understanding of dementia is leading to better care, helping to maintain the personality of the sufferer. It also offers practical, day to day advice from a hands-on perspective, using a narrative structure. It follows the story of an older couple, Linda and Frank. Frank develops dementia. The story covers the first, early signs and the development of the disease; the couple's struggle to manage and find help, the wife's failing health and the search for a suitable care home, and life after Frank goes to live in the home. An index at the back of the book allows readers to look up help on specific topics. Throughout, the narrative keeps a clear Christian perspective. For example, Linda finds that singing familiar hymns as she dusts around the house not only helps her feel better, but lifts Frank's spirits, too, and he will sometimes join in. Each chapter concludes with a short section of devotions for carers and sufferers.

Chapter 1

A Day at a Time

I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me…

PHILIPPIANS 4:13 (NKJV)

Being able to cope with all that life brings our way through God’s grace had been the theme of the pastor’s sermon that morning, and it was Linda’s silent prayer as she backed nervously into her neighbour’s driveway, doing her best to ignore Frank’s directions from the passenger seat. She disliked driving at the best of times, but reversing was the thing she hated most. Normally she avoided it, but because their house was on an awkward bend in the road, Frank insisted they should drive out bonnet first, which meant backing in beforehand. Worst of all was that Frank (not for the first time) mistook their neighbour’s driveway for their own, and insisted on directing her into it. It was no use protesting because he would explode with anger – the anger that had seemed to lodge in him ever since he’d had to give up his driving licence because of his dementia. Frank had always been their driver, and when Linda had had to take over he would either sit morosely or take to barking directions like an ill-tempered Sat Nav. It was like trying to pacify a bear while running off with its cub. Although she was getting better at distracting him and changing his mood, when she was on edge as she was now, it took all her energy simply to get the job done.

She thanked God she hadn’t damaged their neighbour’s roses. Frank didn’t notice that their neighbour’s driveway was lined with rose bushes, while theirs was clear. It was just another of the anomalies caused by the dementia. She thanked God, too, for sympathetic neighbours who understood what was happening. They had lived next door to each other for years, and had known Frank BD – Before Dementia. They’d known him as he had been for most of his life: affable and capable, and that helped a lot.

Nowadays Linda found herself thanking God more often than she had ever done – which was amazing, she thought, now that she had more to cope with than at any other time in her life. She was so grateful that she knew, without a shadow of doubt, that God was real and that he cared for her. She hadn’t been raised in a Christian household, and like millions of others, she had found God by searching. In her early twenties she’d decided that there had to be more to life than this, and had set out to find the meaning of life. A tall order, she’d often thought on reflection, but when you’re young you feel anything is possible. She researched secretly, borrowing books from the library about religions old and new, other cultures, and philosophy. But none held the answer. Then she came across a New Testament, and began to read it as she waited for dinner to finish cooking. Four hours later she was still reading. Some of the pages were spattered with Bolognese sauce because she’d read right through dinner, hardly taking her eyes off, winding the spaghetti on to her fork without looking. “It was an encounter with the Holy Spirit,” she said afterwards. “It all made so much sense. Jesus said he was the way, the truth and the life, so I’d found the meaning I was looking for.” She wouldn’t claim to understand the whole of life and some things that happened were beyond her understanding, but then, human understanding was limited even in the cleverest of people. The basis of both her life and Frank’s, who’d come to faith before they met, was their relationship with Jesus Christ.

Now, almost fifty years later, she hurried to reach her front door before her husband became anxious because he couldn’t find the key he didn’t have any more. Another “Thank you, Lord” when she got there first. Once inside, she suggested having a cup of tea, adding, “Let’s see if there’s anything interesting on television for you.” She switched on the set while he made himself comfortable in his favourite chair and, wanting him to be completely absorbed, she popped one of his favourite old films into the DVD player. As the music swelled with the Dam Busters theme she said, “I’ll go and make that tea now.” Frank nodded as she left the room, and she went quickly through the front door, locking it again behind her. “Lord, keep him contented,” she breathed. It meant the dreaded reversing again, this time into their own drive. It would only take a few minutes and Frank usually didn’t notice the time it took to make the tea, but there was always the chance that he might forget what she’d said and start looking for her, going from room to room. Today, though, he stayed engrossed in the Dam Busters, looking up briefly when she placed his teacup on the side table.

Life before and after dementia

For Linda, the contrast between life before dementia, or BD, and afterwards, AD, was almost beyond description. BD, everything had been so simple, so normal and ordinary. AD, life was incredibly complicated and highly strung, like walking a tightrope and juggling a dinner service at the same time. Whereas BD, most of the day would go by on autopilot as it did for most people, AD life called for major strategies, sometimes two or three in the space of five minutes. Some were to head off an anxious situation, as she had with the front door keys; some were to divert or distract him; some were about choosing the best option at the moment; or sometimes it was simply trying to match what was going on in his mind with different answers or suggestions. She was glad that she was good at multitasking, but she often felt like the Italian traffic conductor in the television commercial, using all her energy to direct traffic but without the luxury of being able to step down from the podium to take whatever it was the person was taking to relieve tension.

Even the simplest thing could be unbelievably complicated, such as helping Frank put his socks on in the morning. It could take several attempts because he would say they weren’t his socks, or they weren’t a matching pair, or they didn’t feel right. On other days he made no fuss and they would go straight on. Frank was often at his best in the morning, though they were not the best times for Linda because her arthritis was worst then. She wondered how much longer she could keep going like this. Six months ago she’d turned seventy, and Frank was seventy-two. He was sixty-six when he’d been diagnosed with dementia, caused by a combination of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. But Linda thought the signs that something was going wrong had been there several years before, when Frank began to have trouble finding the right word, or would forget things and repeat himself. It was as if his mental gears were not meshing, and he took longer to work things out. He was also struggling with depression. His driving had begun to change then, too – imperceptible little changes at first. He seemed to hug the centre line in the road and, although he’d always been a good navigator, he began to lose the way even on familiar routes. It would make Linda nervous, though she would try to hide it because it would make him anxious – something he’d never been behind the wheel. They’d put it all down, then, to the fact that he was planning for retirement two years earlier than he’d expected because of redundancies within the company, and coping with a major life change.

“We’re not as young as we used to be,” they would tell each other, but there were so many small but significant changes in him that she knew, in her heart, that something was not right. “It must be this depression,” she would reason with herself.

Our earthly tent

The word “dementia” derives from a Latin word which means, literally, apart from, or away from the mind. It’s not a mental illness; it’s a progressive degeneration of the brain that is incurable and irreversible. Our brains are probably the most important part of our bodies, because they are our control centre, like the bridge of a ship. We know that the way we communicate and project ourselves to others is enabled by different parts of the brain, and when it is damaged that ability to project is impaired.

Does that mean that the individual, the person known to God, has changed? Most emphatically it does not. From the biblical point of view we understand that if our personalities, the essence of who we are, were the result of the brain we genetically inherit then, when the brain died, so would we. It would be “lights out” for us: the end. But if, as Jesus Christ promised, there is life after physical death with him and, by the sound of it, a better life than most people currently enjoy, then clearly our brains, like the rest of our bodies, are the controls we use to interact with the physical world. When they are damaged our ability to project who we are and what we want to communicate is damaged.

It is important to remember this, because the worst thing for families and carers, and possibly the cruellest aspect of dementia, is watching what seems to be the slow disintegration of a loved one’s personality. Their behaviour changes and they say and do things they have never done before. But put yourself in their shoes for a moment. Try this – imagine you are an advanced-skills driving instructor, and have great pleasure in owning and driving a top-of-the-range car, say a Jaguar. You prefer a manual gearbox because an automatic gearbox doesn’t have the feel or...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.7.2012 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Krankheiten / Heilverfahren |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Geriatrie | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Neurologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85721-359-8 / 0857213598 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85721-359-4 / 9780857213594 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich