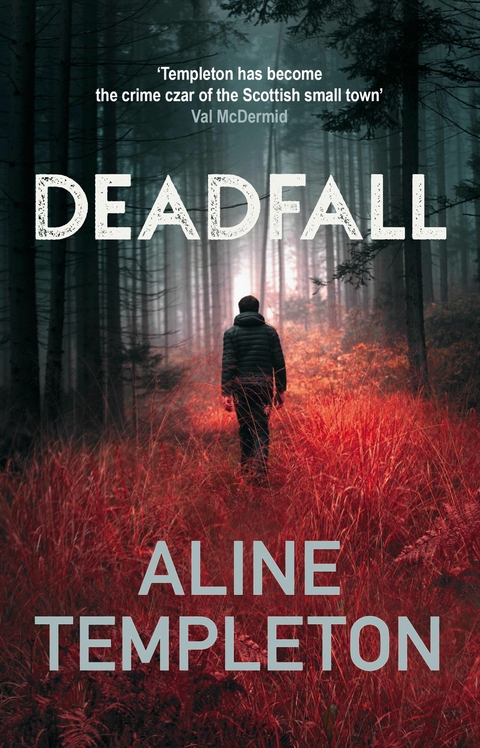

Deadfall (eBook)

352 Seiten

Allison & Busby (Verlag)

978-0-7490-3159-6 (ISBN)

Aline Templeton grew up in the fishing village of Anstruther, in the East Neuk of Fife. She has worked in education and broadcasting and was a Justice of the Peace for ten years. She has been a Chair of the Society of Authors in Scotland and a director of the Crime Writers' Association. Married, with a son and a daughter and four grandchildren, she lived in Edinburgh for many years but now lives in Kent.

Aline Templeton grew up in the fishing village of Anstruther, in the East Neuk of Fife. She has worked in education and broadcasting and was a Justice of the Peace for ten years. She has been a Chair of the Society of Authors in Scotland and a director of the Crime Writers' Association. Married, with a son and a daughter and four grandchildren, she lived in Edinburgh for many years but now lives in Kent.

The first streaks of dawn were no more than a narrow band on the eastern horizon that highlighted the gnarly roots and rough grasses, then slowly widened as it crept up over bark and branches to gild the lowest leaves with early April sunshine.

In the darkness of the trees and bushes the birds were waking with little mutterings and stirrings until the blackbird’s clear whistle, as imperious as the tap of a conductor’s baton, signalled the start of the chorus. Then all around responses began – somewhere the croon of a woodpigeon, the aggressive shouting of a wren, then more twittering and cheepings as the light grew.

It was cold still, with patches of ground frost in the shade and even in the open spaces the dew glittering on the grass was icy cold.

But Lachie MacIver was used to that, and to rising early; he was getting old now and his mattress, worn thin with use, pained him so that he was glad enough to rise at first light. He lived in the shepherd’s bothy on the edge of the estate; they’d sold off land after the old lady died and there hadn’t been sheep for forty years, but when they’d no further use for him they hadn’t turfed him out. They’d just let it decay, and now there were cracks in the walls and rain could find its way under the rusted corrugated-iron roof that lifted a little in a high wind.

Do-gooders he despised had tried to move him out, but his answer had been short and to the point. Very short. Here he was his own man, walking the five miles to the village for his pension and supplies and other times living off the land, as he called it.

There was a pheasant shoot across the valley and they were early risers too, and easy pickings. The sun was up by the time he set off, the shotgun broken over his arm – his father’s old gun the polis didn’t know he had. Plenty folk did know, but round here they wouldn’t clype.

He set off to take the short-cut through Drumdalloch Woods. They got nasty if they caught him doing that; he wasn’t above taking a fat pigeon if there was no one around – they were daft about birds. By now he’d need to be careful; there were youngsters who’d nothing better to do than checking on wee machine-things they’d set up and writing stuff down.

Lachie paused, listening, as he reached the trees. Even in his heavy boots he could move silently but he’d hear them coming – clumsy, snapping twigs and swearing when they tripped on something. This morning there was only the racket the birds were making and beneath their songs he could feel the deep silence of the woods.

It had a curious power and it was tempting just to stand, losing himself in it, but he needed to get on. He headed for the glade near the middle, crossed by a track leading to Drumdalloch House, the backbone for multiple branching tracks and the route anyone doing the early morning checking would take. He was ready to walk quickly across when something caught his eye.

A huge oak, an ancient giant, stood at the far end and someone was lying across its gnarled roots. He stepped back out of sight. They often made their daft checks from funny positions and there was a rough wooden nesting platform above, right enough, but it had fallen off and the way the person was lying didn’t look right.

When he got nearer he caught his breath. It was a woman, and he recognised her – Perry Forsyth’s wife. Wearing jeans and a padded jacket, she was lying on her back against the oak with one foot twisted under her, like she’d maybe reached up to the platform and pulled it down on top of her. It looked like it had missed her, but then she must have tripped as she ducked out the way.

This was a right mess. She wasn’t moving and he could see a bloody wound on her head. Must have given it a right good bash against the root. Maybe she needed help – but he shouldn’t be here, and if he stayed they’d maybe say he’d done something to her.

With an anxious look around, he went to check – not too close, being careful to tread on firm ground. And even from there he could tell she was dead.

The open eyes, glazed, the jaw starting to sag, the little trickle of blood running out of one ear – oh yes. An old soldier, he’d seen enough death before, in battlefields he still revisited on one of his bad nights.

This would be hard on her bairn, but there was nothing Lachie could do for her. Someone would find her soon enough. With another nervous glance he retreated, disappearing into the trees. The pheasants were safe for now and later he’d walk to the village to pick up any news.

He’d like to be sure they’d found her. He wouldn’t want to be left like that himself; the flies would find her first and soon other woodland creatures would be running or crawling or more horribly squirming here to perform their interconnected tasks as undertakers.

The white-faced student, who had been doing a check on the data loggers on the trees chosen for the current study, had come stumbling into the kitchen at Drumdalloch House, tear-stained and so shaken she could hardly get the bad news out.

As if he hadn’t taken it in, Giles Forsyth stood still as a statue; only the furrow between his heavy grey brows deepened. Beside him his daughter Oriole gasped, almost dropping her coffee mug, and her other hand went to her throat.

‘Helena – dead? Are you sure? Where is she?’

‘I’ll show you. Yes, it’s – well, sort of obvious.’ Her voice broke. ‘Fell and hit her head badly, I think. There’s great tits nesting in the box above – she probably went to make a recording and overbalanced.’

Giles cleared his throat. His voice was perfectly level as he said, ‘You go with her, Oriole. I’ll phone the police.’ His daughter nodded and went out, her arm around the girl who was still trembling visibly.

He didn’t move for a few moments after they left. He wasn’t sure he could. A man of his generation, he gave no outward sign of the inner maelstrom of grief, helpless rage at fate and the bitterness of blighted hope. His daughter-in-law, lovely Helena, who had wholeheartedly shared the plan his own children were determined to thwart, was gone, and those children would destroy all he believed to be important the day he was safely dead himself.

His grandmother had dinned into him that these woods were a sacred trust, to be left to him, bypassing his older brother because he’d shared her passion for the glory and majesty of the ancient trees, sanctuary for generations of woodland birds, with records going back more than a hundred years. He’d tried to pass that on to his children but he’d failed. Oh, Oriole paid lip-service but she’d never be able to stand against Perry. The historic legacy meant nothing to him.

He’d called his children Peregrine and Oriole; Perry had always mocked the sentimentality and had raged when Helena had encouraged the son named James to call himself Jay.

Dear God, Jay! A mother’s boy, undoubtedly; what would it do to him to lose her, aged ten? Giles would do his poor best for him, but the scar would be deep and disfiguring – and Jay would be all Perry’s child, ready to be shaped and no longer a pledge for the future of the woods.

He was old and tired, not fit for the struggle. Perhaps he could train himself not to care what would happen when he wasn’t there to see it, but his mental torment felt like physical pain, deep inside him. They said you could die of a broken heart. Perhaps you could.

He straightened his shoulders and walked stiffly over to the phone. ‘Giles Forsyth, Drumdalloch House, Kilbain … Fatal accident,’ he said.

Apart from going into the village where he’d learnt she’d been found all right, Lachie stuck close to the bothy. He could hear activity in the woods and catch sight of folk moving around, but he wasn’t going to get caught up. The polis asking questions would mean trouble.

Next morning he took the ferret from her cage, a pretty jill with a brown bandit mask across a silvery face, petting her briefly before she nestled down in his pocket in patient expectation.

He collected the purse nets and the wooden pegs he’d whittled himself, then, a spade over his shoulder, set out for the south-facing slope at the end of the field, honeycombed with rabbit holes. There were no rabbits visible; dawn feeders, rabbits, and if he’d wanted to shoot one he’d have been out at first light. Now, though, they’d be asleep with full stomachs.

There was a small burrow he and the ferret both knew, one that past experience had shown had fewer escape tunnels than the larger ones. Moving quietly, he stretched the net across a tunnel opening and had just started on the pegs when he realised someone was coming up behind him, quiet on the soft grass.

Lachie turned. Jay Forsyth’s face was blotchy and his eyes were swollen, but he wasn’t crying and Lachie said only, ‘Never heard you coming. Make a poacher of you yet.’

The...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | DI Kelso Strang |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller |

| Schlagworte | Crime • Deadfall • DI Kelso Strang • Scotland • Suspense |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7490-3159-X / 074903159X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7490-3159-6 / 9780749031596 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 507 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich