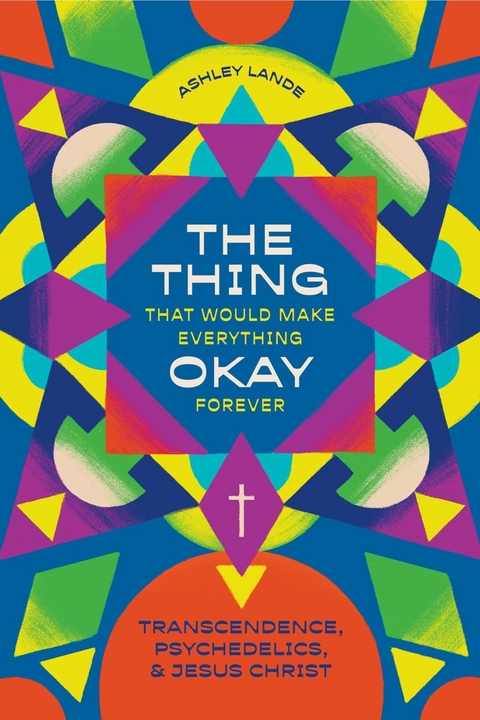

Thing That Would Make Everything Okay Forever (eBook)

260 Seiten

Lexham Press (Verlag)

978-1-68359-761-2 (ISBN)

Ashley Lande is a writer and artist based in rural Kansas, where she lives with her husband, Steven, and three children.

For years, psychedelics were my religion. All I ever wanted was The Thing That Would Make Everything Okay Forever, the panacea, the cure for what plagued me. From those first moments when I tasted the earthy pulp of a psilocybin mushroom, it was love. Psychedelics were my sacrament. They shot me into cathedral vaults. The promise of eternal life through chemicals glittered seductively, but hid a yawning abyss. The Thing That Would Make Everything Okay Forever tells my story of psychedelic devastation and spiritual rescue. It chronicles my trajectory from acid enthusiast to soul-weary druggie to psychedelic refugee. I finally found The Thing That Would Make Everything Okay Forever in the last place I thought to look.

Ashley Lande is a writer and artist based in rural Kansas, where she lives with her husband, Steven, and three children.

The last time I ever tripped, I ate mushrooms I’d grown myself.

Like an anxious mother, I fretted over my spore jars, frequently checking the cabinet where they germinated in the secret dark until a web of snowy white began to crystallize against the glass. I breathed a sigh of relief when I saw the embryonic fungus proliferating like frost on a window: my manna. Mother Nature had provided.

I transferred the star-seeded soil to a Styrofoam cooler over which I hovered, checking every few hours, waiting for just the right time to harvest: when the mushrooms had grown an inch or two, their heads hooded like medieval monks and weaving toward the light on tender stalks, their caps poised to bloom into a gilled umbrella and drop an invisible rain of spores. I spread out my hands and blessed them with my scrambled patois of two-bit Sanskrit and new-age-inflected prayers. “Ommmmm,” I chanted over them, saturating them with the vibration of the Universe.

This would work. It had to. It felt as though my very life depended upon it.

For years, psychedelics had been my religion. They were my key to transcendence, my portal to a kaleidoscopic domain that was sometimes a palace of ecstasy. But the drugs didn’t work anymore. I couldn’t seem to have a good trip. These substances, which I regarded with as much reverence as a Christian might look on the baptismal waters, now unnerved me before I even let the blotter paper turn to pulp on my tongue or sifted the grainy bits of a psilocybin mushroom in my mouth.

I was once sure they had shown me the face of God. But lately they’d shown me nothing but panic, disorder, and disintegration. I wanted to be borne aloft to epiphanic heights and sputtering mania again, like the midnight I’d spent tittupping down the sidewalk of midtown Kansas City pontificating to anyone who’d listen that I myself had become LOVE LIGHT BEAUTY TRUTH WISDOM MAGIC JOY. Or the day my husband and I, newly married after two months of dating and still surfing the heady wave of infatuation, had hiked through the Missouri forests high on acid and the very trees seemed to pour forth speech and the rocks cry out—saying what, I didn’t know. But everything, tessellating electrically in high summer glory, whispered of mysteries untold. I hungered to go deeper, further. I yearned for an endpoint, the Thing That Would Make Everything Okay Forever. Psychedelics always seemed to promise a shimmering Shangri-La.

But nowadays, even the counterfeit kingdom evaded me. I was left slumped in the fetid dungeon of my soul, exposed to an infinite cavalcade of gruesome images and stultifying fear.

From the beginning, I’d learned and adopted psychedelia’s dogma: psychedelics aren’t addictive, we all said, unlike narcotics, which trigger a dopamine flood. Lab rats will press the lever for psychedelics only once, whereas the poor creatures will pound unto death the levers dispensing cocaine or heroin. But I was the outlier, the freak rodent that pressed again and again and again, despite trips that induced unspeakable terror and enduring trauma, desperate for another taste of the rapture that had characterized my earlier experiences. I hit the lever, and I hit it again, drilling it with increasing desperation, and I would keep hitting it until I saw God or lost my mind. I know now what I wouldn’t countenance then: I was addicted to psychedelics. I was a drug addict.

An addict’s brain engages in all manner of acrobatics to justify her idol. Sourcing must be the problem, I concluded. Yes, that made perfect sense. Dealers were all about filthy lucre, but this was my sacrament, my medicine. Plus, I was tired of having to pander to dealers who lorded their power over small tyrannies, casually pretending you hadn’t come for what you’d actually come for. I’d spent too many useless kowtowing hours in dimly lit rooms suffused with marijuana smoke and wallpapered with mandala tapestries, a captive audience to Adult Swim reruns and stupid stoner movies. If I could grow my own mushrooms, infusing them with the right energy and love, I reasoned, I’d be back on The Path. My stairway to heaven would spiral high once again.

This wasn’t my first attempt at do-it-yourself drugs. Years before, I’d bought a vintage pamphlet with instructions on synthesizing LSD. I’d barely passed high school chemistry, and that only because Sister Harriet, who ruled with an iron fist and imposed impossibly high standards, had unexpectedly retired three days into my junior year. The replacement teacher was a young woman barely out of college, and the bolder girls in class succeeded in coercing her into lighter assignments and open-book tests. I escaped with a C minus. My bright hopes faded and my palms began to sweat as I leafed through the LSD pamphlet and encountered those dizzying equations again, the chemical ciphers that harried my very literary brain.

Mushroom-growing seemed elementary by contrast, so when my husband got word through friends that some spores might be available, I pounced on the opportunity. As soon as he brought home the syringe of invisible psilocybin spores suspended in water, I took to the task of cultivating them with reverential fervor. I filled the jars with vermiculite. With a dropper, I meted out the spores among them. I screwed the lids on with plastic-gloved hands, exercising a degree of diligence I rarely applied to other tasks. I arranged the jars in a neat row in the cabinet next to our shower—the perfect little climate of dark and humidity. And I waited.

When harvest day arrived, I gathered my fully grown mushrooms and dried them on a screen in the sun. I’d been a good caretaker, I was certain. I’d adored them. I’d assured my ticket to ecstasy. I’d paid the offering, granted the worship due, followed every rule with religious devotion.

We weighed out six grams of dried mushrooms and slid them into a blender with juice. There was a strange gritty earthiness overlaying the citric tartness, like a muddied orange slice. The sour and bitter tang made my mouth water—my body protesting at the toxin entering my digestive tract. As we waited, I placed a Ravi Shankar record on the turntable and sighed as the darting sitar twanged its staccato dance in warm analog, buffered by a galloping tabla rhythm. As the walls remained as static as ever, I began to fret: Maybe I grew them wrong. Maybe the spores were a bust—maybe they weren’t even psilocybin. But when these questions begin percolating is always, I knew, when it happens.

The room began to change. The walls wavered and breathed, and I inhaled that familiar shift in the air when suddenly the very molecules became sentient, glowing with a consciousness of their own, respirating and crackling with neon electric current. Our model Mayan temple, which my father-in-law had built according to my exacting standards and whose vertical surfaces I’d painted in geometric diamonds, began to shudder and wink. The colors saturated to Day-Glo intensity and flooded down the stairs of the structure in braided streams.

Undulating prismatic lattices overlaid every surface, swooping and diving and swallowing one another only to be continually birthed anew in ever-richer complexity. These mushrooms were strong. Oh, they worked all right. But something was wrong—the same thing that had been wrong all the other times, the same bitter taint of poison that blackened the parade of bad trips I’d endured for the past couple of years. Despite my careful planning, despite my religious observance of The Rules, it was happening again.

As soon as the sumptuous spectacle of color and light assailed my blown-out pupils, a discordant, doom-laden note at the very heart of the cosmos seemed to strike hard and resonant in my gut, shaking everything, destabilizing the entire universe, which now threatened to go spinning off into oblivion. The mushroom was betraying me. The Universe cackled malevolently. I had been brought low, and now I would die, and there was no one to help.

The weight of it all made my body feel heavy. I slowly bent my knees and made the perilous voyage to the floor, which seemed to recede ever farther from me, an Alice whose wonderland had begun to feel alien and hostile.

My body was stone now. I no longer could lift my eyes upward. I turned my face to the floor, hoping for some reprieve in the humbling. But everything everywhere was riotously kinetic. Nothing rested, nothing was silent; the whole world was a whirling, pulsing, dinging, strobing pinball machine. Every whorl in the hardwood floor, every pinpoint of surface collapsed and expanded into infinitely fractalizing visual symphonies, a honeycomb of eyes, a fretwork of maximally intricate geometric patterns.

I lay all the way down, surrendering my body to an earth I prayed would swallow it whole. It was an arduous journey. Impossibly, I summoned the strength to turn my eyes to my husband, who was lounging on the couch as though the greatest disaster ever to befall the universe was not occurring and everything was totally groovy. I tried hard to stop panicking, but my efforts to calm myself—breathe, om, remember you are a part of the Universe and the Universe is a part of you—were like pitching bucketfuls of water onto a blazing sun, where they hissed a dying lisp before vaporizing. My anxiety increased to a buzzing pitch of terror. I was alone in a hostile cosmos. I strained to remember language. My mouth opened and closed in a parched and pathetic pantomime.

“Um, I think I really am dying this time,” I finally said, my words small brittle things against the onslaught of yawning fear, weak bits of Morse...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Bellingham |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Schlagworte | Christian conversion story • Christian personal growth memoir • christians and drugs • christians and psychedelics • drugs and jesus • faith and self-discovery • finding faith after psychedelics • finding God after psychedelics • healing through Christianity • psychedelic experiences • psychedelics and mushrooms and the cross • psychedelics and religion • psychedelics and spirituality • Spiritual transformation |

| ISBN-10 | 1-68359-761-3 / 1683597613 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-68359-761-2 / 9781683597612 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich