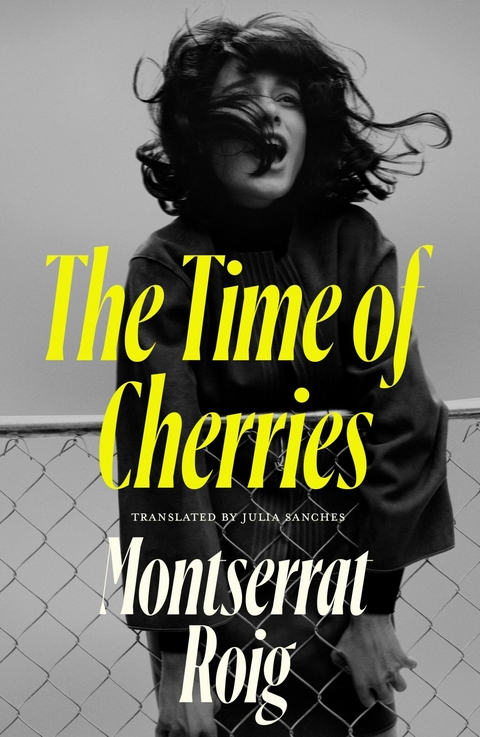

Time of Cherries (eBook)

303 Seiten

Daunt Books (Verlag)

978-1-914198-30-4 (ISBN)

Montserrat Roig i Fransitorra Catalan journalist and writer of novels and short stories, was born in 1946. In her writing, Roig confronted her own political, cultural and literary past in the search for her identity as a writer in a rapidly changing Catalonia. She won, among other awards, the 1976 Premi Sant Jordi de Novel·la for El temps de les cireres and the 1978 Crítica Serra d'Or prize for historic journalism for Els catalans als camps nazis. She died from cancer in 1991.

Natàlia decided that she would go to her aunt Patrícia’s flat instead, on Gran Vía and Bruc, when she returned to Barcelona. Her brother Lluís, who’d been married to Sílvia Claret for eighteen years, lived on Carrer Calvet, near Via Augusta, in the upper part of the city. She wouldn’t have stayed with him anyway. Not because of Sílvia, with whom she at least shared a love of cooking, but because of Lluís. Natàlia had forgotten a lot in the twelve years she’d been away, yet she hadn’t managed to wipe from her memory the sarcastic smile on her brother’s face the day he rushed her to the clinic in his car. Natàlia had been at risk of sepsis – By all means, screw around, but think things through first, use your head, he’d told her as she writhed from the pain in her lower belly.

The airport seemed much larger and brighter, and far busier than Natàlia had imagined. It was bustling, with people of all stripes wandering about and air-traffic-control lights signalling the frequent arrival and departure of planes. As she waited for the tapis roulant to deliver her suitcase and two handbags – scant baggage – Natàlia discreetly observed the people around her. The man who had lectured her about the impressive performance of Puig cologne – ‘we export it all over Europe, our little Catalan cologne has travelled the globe’ – thankfully stood at the opposite end. Two Irish nuns huddled close together, looking askance. The woman with flaming red lipstick, like a model in the 1950s, gazed contentedly at the display windows facing the terminal – I wonder if she’s looking for someone – and the man reading the New Statesman while smoking a pipe, who looked like a British Council teacher, checked his watch against the airport clock. The baggage finally arrived. Ant-like, the passengers filed tidily and somewhat drowsily towards the exit. Natàlia Miralpeix hesitated: she could take the Ibèria bus, which would drop her at Plaça Espanya, or she could take a taxi. She had changed her last few pounds, hardly anything, really – poor Jimmy and his capital – at Heathrow. Thankfully, the pound was stronger now and the exchange had worked in her favour.

She hailed a taxi, then turned around to take one last look at the airport. She recognised Miró’s whimsical, childlike strokes and smiled. I’m home. She climbed into the car. ‘Gran Via and Bruc, please.’ The cabbie’s eyes were leaden in the rear-view mirror. He glanced at her every so often – I wonder how I must seem to him. Is it that weird for a woman pushing forty to be travelling alone? Maybe it’s the jeans … Jimmy, who dressed more shabbily than she did, had talked her into buying a pair at Portobello Market. If there’s one thing you’ve got going for you, it’s your arse, he’d said. You’ve got a bullfighter’s arse, and these jeans are a nice, snug fit – the snugger the better. The sky over Barcelona was the same heavy, solid grey of past springs. It was as if a single mass of clouds were slowly descending on the city, skimming the edges of the trees. A narcotic, headachy sky. What we need is a good storm, the cabbie said, addressing Natàlia with his eyes. All she could see of the man was a short, thick neck with rolls of skin down to the top of his spine and, in the mirror, a small rectangle of face, from his forehead to the bridge of his nose. Outside, the landscape was cut through with car cemeteries, shades of brown and grey, broken engines, shopping trolleys, dusty leaves, crumbling street gutters, dead trees, and the Ermita de Bellvitge, itself surrounded on all sides by concrete blocks. Natàlia gazed out at cypress trees smothered in dust and thought of the yellow-tinted days when she had visited the chapel with her father. Other cars zipped past, centimetres from the taxi. They warned me: there’s more money now, you’ll see. Natàlia rolled up the window.

Two days had gone by since Puig Antich was killed, and Natàlia told herself she wasn’t naïve enough to expect things to feel different. She thought of Jimmy’s new friend, Jenny, and the desolate look in her eyes. I went over to say goodbye. The evening before, I’d cooked them my special roast chicken. See, you take the chicken, ask them to gut it for you, then slip in a couple of cubes of Maggi or something of the sort, and a halved lemon. She had explained all this to Jenny because roast chicken was a favourite of Jimmy’s. You’re an excellent cook, Natàlia, he used to tell her when they lived together in Bath. I got tipsy on sangria – too much ginger, maybe? – and knew for sure I’d have indigestion later. I can’t eat much rice because it makes me feel bloated. Besides, British chickens are fattier than ours. Before the sangria, I had three glasses of sherry and then some of that dreadful red wine they sell at the pub, the kind that comes in those massive bottles. But Jimmy wanted sangria. It’s our goodbye, isn’t it? Even if Jenny is here … Even though Jenny was there, Natàlia had made her special lemon-stuffed roast chicken – tubby Mrs Jenkins, the sweetheart, had let her use her oven. ‘My dear, I completely understand …’ she had said, with a smile. The English will always understand everything and happily loan you their oven for a leaving do. Jimmy had been charming and even kissed her a couple of times, partly as a joke and partly in earnest. Jenny set the table and warmed the dishes up beforehand so they wouldn’t have to eat their chicken with cold rice. The whole affair had been very nice, indeed, and Natàlia saw for herself that Jimmy had in fact changed. He finally had the set-up he had always dreamed of – in Liverpool, where he’d grown up – although he said he would always remember their time in Bath ‘as some of the most wonderful days of my life, I promise’. And he was so earnest and focused when he said I promise that Natàlia couldn’t help but laugh. This was what he, Jimmy, said to her, Natàlia, as they enjoyed a cream tea in the Pump Room, a dining hall with a neoclassical ceiling and large picture windows that looked out onto the old Roman baths. As Jimmy smeared butter and jam on his scone, Natàlia told him that Jenny was absolutely lovely. It would have been pointless to add that she was a perfect fit for this new chapter in his life – that was clear enough. Jenny was a Hogarth through and through – rosy cheeks, resolute chin, cat-like eyes, brown hair, and a nose that tended to go reddish in cold weather. Her delicate, fair skin seemed always on the verge of cracking. When she first met her, Natàlia thought Jenny was fortunate to be petite and brunette, and to have bright, cheerful eyes and, most of all, a button nose that turned red the second it hit the cold. English films were easy to identify, not only because of the sweeping meadows and red-brick houses but also because of the actresses’ noses. A nose like Samantha Eggar’s in The Collector, the film that had made Natàlia fall in love with Hampstead, was hard to forget. Must you really go? Jimmy asked, adding a dollop of clotted cream to his scone. Natàlia said yes, and yes again as they strolled along the River Avon – it was the swans that brought tears to her eyes, though she still couldn’t say why – yes, she must, Natàlia thought, she must go home to Barcelona. If I don’t leave now, I never will, I’ve been gone nearly twelve years. Why go back? He asked. I don’t know, she said.

The day after their farewell dinner, Natàlia stopped by Jenny’s house. She had left the oven dish and needed to return it to Mrs Jenkins. That’s when Jenny told her she’d heard something on the radio about a Spanish anarchist being executed – Puchantik, I think he was called. Natàlia let the dish fall against her skirt – she’d bought a black corduroy one that morning and sworn to herself it was the last – then sat on the arm of one of the easy chairs next to Jenny’s chimney. At first Jimmy told her he wasn’t going to live with Jenny, but the house had a little garden, and it was tempting, since every now and then a gull would alight there, having lost its way from the sea; besides, he was moving to Liverpool in four weeks, and yes, maybe he would marry Jenny after all. Jenny and Jimmy were the same age, both twenty-five, it was only natural. Natàlia sat in silence for a while. Jenny was a little alarmed, and she opened her cat-like eyes very wide – Oh, my dear! Did you know him? – and who can say what Jenny must have thought, seeing Natàlia like that.

The problem was that Natàlia didn’t know how to explain any of it to Jenny. She could’ve said, It’s like Proust’s madeleine, see, him dying right as I’m about to go back … The problem was that Natàlia had left the same year as the miners’ strike in Asturias – she and Emilio had sung ‘Asturias, patria querida’ and ‘Astúries, llibertat!’ up and down La Rambla de Barcelona until they were both hoarse – and as Grimau’s arrest. Grimau, who...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Julia Sanches |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Klassiker / Moderne Klassiker |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-914198-30-1 / 1914198301 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-914198-30-4 / 9781914198304 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 344 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich