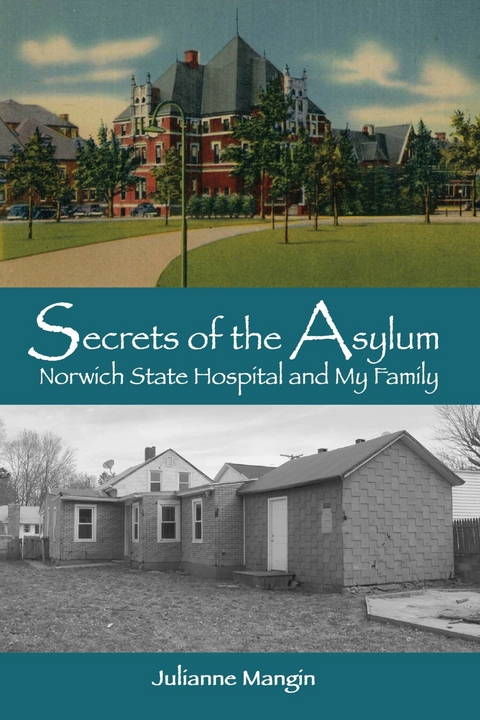

Secrets of the Asylum (eBook)

398 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-0998-2 (ISBN)

Retired librarian Julianne Mangin was a reluctant genealogist -- at first. But after acquiring her ailing mother's genealogy files, something drew her into the family history. Maybe it was years of listening to her mother's cryptic stories of her childhood which featured a delicatessen, a state hospital, a county home for neglected children, and a father who disappeared. Even though Grandpa divorced her mother and never got her out of the county home, Mangin's mother defended her father's absence and called him a wonderful father. At first, all Mangin meant to do was organize her mother's files so that they could be stored more compactly. But it wasn't long before she began noticing errors, omissions, and discrepancies in her mother's research that cast doubt on the family stories. Thus began her transformation from reluctant genealogist to relentless family historian. She acquired her grandmother's patient record from Norwich State Hospital and the secrets just spilled out. There were four other women in her mother's family who were patients at state hospitals, three of them at Norwich State Hospital. And there was evidence that Grandpa might not be her mother's father. Reading the transcripts of her grandmother's interviews with hospital staff, Mangin unearthed a dark secret at the heart of her mother's childhood. Through her research, Mangin uncovered her French Canadian heritage and delved into the history of the care of the mentally ill in the early 20th century. She learned how poverty and mental illness loomed over the family's fortunes. Using patient records, genealogical methods, and DNA testing, Mangin has pieced together a family story that reads like a Dickens novel Weaving in what she learned about intergenerational trauma and the consequences of family secrets, Mangin has created a testament to the power of family history to empower people and heal old wounds.

Chapter 1

Mom’s Stories

Mom’s stories about her childhood and family history were like bursts of steam from a pressure cooker – brief, tantalizing, and at times, disturbing. She started telling me these disconnected anecdotes when I was about eleven years of age. The most frequently repeated story in Mom’s canon went something like this:

My mother had an uncle who set her up in business running a delicatessen. During the Great Depression, the business failed. When I was seven years old, my mother became mentally ill and was sent to a mental hospital. I was taken from my father and put into the county home.

In just a few sentences, Mom would sum up a family tragedy that was Dickensian in proportion; a girlhood weighted down by financial disaster, her mother’s insanity, and separation from her father. It puzzled me that her emotions didn’t match up with the scale of her family’s misfortunes. She would bring up the stunning facts of her childhood in the same tone of voice she might use to tell me what she was planning to fix for dinner that night. When she finished telling the story, Mom would evade the inevitable questions her story prompted with facile explanations and the occasional shoulder shrug. Although she admitted that her father had divorced her mother while she was in the mental institution, and that he had never tried to get her out of the county home, Mom swore that Grandpa had been the most wonderful father ever.

The moments she chose to tell the story were brief and spontaneous. We might be folding laundry together when Mom would put down the pair of socks she had just matched up and blurt out the story. Or I might come upon her while she was sitting at the Singer sewing machine in the dining room, stitching up the seam of a dress, when she’d suddenly be overcome with the urge to spit it out. She might even tell me the story while the two of us were alone in the car, driving to the grocery store or a doctor’s appointment. There’s one instance of her telling that story that sticks in my mind to this day.

It was the late 1960s, and I was about thirteen, when I wandered into the family room after coming home from school. Mom was sitting on the piano bench, with a shoe box on her lap. She was a petite woman with dark eyes, wavy brown hair, and a light olive complexion, just like her French Canadian mother. Although I was also small in stature, I was different from Mom in other ways. I had light brown hair and fair skin, with a sprinkling of freckles across my nose and cheeks. Mom used to tell me I got my coloring from Grandpa, her fair-haired Anglo-American father.

I put down my textbooks and pulled up a chair next to her, still wearing my Catholic school uniform – a blue plaid skirt, a light blue blouse with a round collar, and saddle shoes. The light from the late afternoon sun shot through the window behind her. Something about her back-lit head and the halo-like effect of the light made Mom seem mysterious, and yet somehow approachable. She was going through a shoe box of things that had once belonged to Grandpa, the father she adored. It was a potentially charged moment, but if she was feeling any strong emotion – grief, anger, love – she didn’t let on. It was in this room with the spinet piano, the television, the shag rug, and the leatherette reclining chair, that Grandpa had died a few years earlier.

There was still a sense of Grandpa in this room, which had served as his bedroom for the last few months of his life. Maybe it was the faint smell of nicotine which permeated everything he owned. Grandpa was a chain-smoker, just like Grandma had been. When he moved into our house after Grandma died, he brought with him a small television set that reeked of cigarette smoke. After Mom washed its yellowed plastic shell, it lightened to an off-white and didn’t smell as bad. Mom didn’t allow smoking in the house, but the odor attached itself to his clothes and to the small personal items that she hadn’t been able to scrub. From the box, Mom pulled out Grandma’s pocket prayer book, printed in French and Latin, its leather cover cracked with use, and a postcard photograph of Grandpa as a young man. She gazed at her father’s image lovingly, then looked up at me and said, “This is my father in his World War I uniform. Isn’t he handsome?”

When I was thirteen, it was unusual to have Mom’s attention all to myself. At the time, there were eight of us living in a brick Cape Cod house built in the early 1950s and expanded in 1962 to accommodate our large family. I am the third of six children. I have an older sister and brother, two younger sisters, and the youngest, another brother. The first five of us were about eighteen months apart in age. The youngest came along after a break of four and a half years. I sometimes felt like my parents barely noticed me in the blur of activity in our home. This was why I savored this moment alone with Mom, even though I knew already what she was about to say. I hoped that this time she would embellish the story with new details or perhaps a revelation of how she had felt about her childhood. If she didn’t, I had some questions ready.

Mom looked up from Grandpa’s photograph and began her usual spiel. “My mother had an uncle who set her up in business, running a delicatessen.” When she got to the part about being taken away from her father, I summoned up the nerve to ask her why Grandpa had never tried to get her out of the county home.

As always, she defended him, saying, “He was poor and uneducated and couldn’t take care of me,” and then added, as if it explained everything, “In those days, they wouldn’t let a man raise a daughter alone.” I had my doubts about this explanation, but I sensed that she needed to believe this so that she could preserve her opinion of Grandpa as a loving father. I asked, “How did you feel about growing up in an orphanage?” Mom bristled at my question and corrected me immediately. “The county home was not an orphanage. We all knew where our parents were.” While my mind was churning on the question of whether it was worse to have no parents at all, or to have living parents who couldn’t – or wouldn’t – take care of you, Mom had begun to put away Grandma’s prayer book and the photograph of Grandpa. As she returned the shoe box to its place in the closet, it was obvious that the discussion was over.

Mom had other tales, equally brief and mysterious, which reached further back into her own mother’s family history:

When my mother was a little girl, she lived with her family in a shed behind a relative’s house. Her sister Pauline was born there.

My grandfather deserted his wife and children and went back to Canada, and my grandmother became insane. Some doctor thought it was a good idea to pull out all of her teeth.

My mother was raised by her Aunt Rose, who was unhappy about having to raise her sister’s children.

My mother met my father when he was delivering coal to the house. Her family did not approve of him.

One of my mother’s relatives committed her to the mental hospital. While she was there, she was given electroshock treatments.

Even though Mom had never been good at expanding on her stories, some of them had such intriguing details that I had to ask her questions anyway. Why was Grandma living in a shed? What kind of doctor pulls out someone’s teeth to cure insanity? Mom would become defensive, as if she felt she was being interrogated. “That’s what I was told,” she would say, with a hint of irritation in her voice, and drop the subject. As I child, I assumed that she was telling me what she knew from her own experience. It wasn’t until I was well into adulthood that I made the connection between the gaping holes in Mom’s stories and the fact that she’d been separated from her family for a significant chunk of her childhood. I realized that the things she told me, she could only have learned from Grandma, who was paranoid, delusional, and therefore not the most reliable source. But Mom held on to her stories just as they had been told to her. For most of my life, I couldn’t figure out why.

By the time I was a young adult, trying to figure out on my own the meaning of family and relationships, I could only look back on my mother’s stories with bewilderment. Although I accepted that Mom’s knowledge of her own family history was limited, it seemed to me that there had to be more to the story. I knew where Mom, Grandma, and Grandpa had ended up many years after the tragic disintegration of their family. But with the meager information Mom had given me about their lives, I couldn’t figure out how the three of them had gotten from point A to point Z, because points B through Y were missing. I could only piece together a picture – not much more than a sketch, really – of what had happened to Grandma, Grandpa, and Mom. What follows is most of what I knew about their history until my retirement in my fifties when I began to dig into the secrets of the asylum.

Grandma spent a dozen years in a state mental hospital during the 1930s and 1940s. Meanwhile, Grandpa divorced her. Mom had told me about how jealous and ill-tempered her mother had been, so I could hardly blame him for wanting to end the marriage. Even though her schizophrenia was never cured, Grandma was eventually discharged from the state hospital. However, instead of returning to her family, she moved from a patient ward to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.9.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-0998-2 / 9798350909982 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich