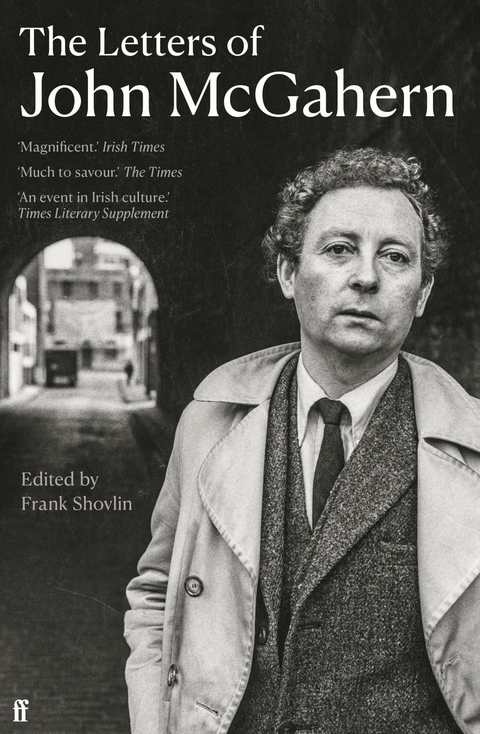

Letters of John McGahern (eBook)

800 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-32667-9 (ISBN)

Born in 1934, John McGahern was the eldest of seven children, raised on a farm in the West of Ireland. The son of a Garda sergeant who had served as an IRA volunteer in the Irish War of Independence, he was devastated by his mother's death when he was nine. An outstanding student, McGahern studied at University College Dublin and became a teacher, but was dismissed when his controversial second novel, The Dark, was banned by the Irish Censorship Board. He moved to London to continue writing and met his future wife, Madeline Green, in 1967, with whom he remained until his death in 2006. The author of six acclaimed novels and four story collections, his novel Amongst Women, was shortlisted for the 1990 Booker Prize and made into a BBC TV series. McGahern held numerous academic posts internationally and was awarded honours including the Irish-American Foundation Award, an Irish PEN Award, the Prix Ecureuil de Littérature Etrangère and the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. On his death in 2006, McGahern was celebrated by The Guardian as 'the most important Irish novelist since Samuel Beckett.'

I am no good at letters. John McGahern, 1963John McGahern is consistently hailed as one of the finest Irish writers since James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.This volume collects some of the witty, profound and unfailingly brilliant letters that he exchanged with family, friends and literary luminaries - such as Seamus Heaney, Colm Toibin and Paul Muldoon - over the course of a well-travelled life. It is one of the major contributions to the study of Irish and British literature of the past thirty years, acting not just as a crucial insight into the life and works of a much-revered writer - but also a history of post-war Irish literature and its close ties to British and American literary life. 'One of the greatest writers of our era.' Hilary Mantel'McGahern brings us that tonic gift of the best fiction, the sense of truth - the sense of transparency that permits us to see imaginary lives more clearly than we see our own.' John Updike

INTRODUCTION

‘I am no good at letters’: so writes a twenty-nine-year-old John McGahern to Mary Keelan, an American graduate student whom he had met in Dublin in the summer of 1963 and with whom he had entered a lively epistolary friendship. After confessing this perceived weakness, he explains more about his relationship with the letter as a form: ‘I have written more to you than to anyone ever, there’s something unreal about them, they’re neither life nor anything, but it’s nice for them to come.’1

And yet, despite this avowed discomfort in the face of letter writing, McGahern would write a host of revealing, forthright and intriguing missives to a variety of people over the course of his life, from close friends to professional contacts, fellow writers and family. That said, it was clear from the outset of this editorial task that I was not dealing with a writer like W. B. Yeats or T. S. Eliot, where multiple volumes would be needed to chronicle the various communications sent out to the world by the author over the years. ‘I don’t like writing letters,’ McGahern tells one correspondent in 1960. ‘So I seldom do – which physics nothing.’2 He was not a voluminous letter writer, though there is no year – and not many months in any year – for which I could not find a letter or an email between the first adult communication contained in this volume, penned to his good friend Tony Swift in December 1957, and March 2006 when, in the midst of his final illness, he dictated emails and letters to his wife Madeline. Published here are about three-quarters of the letters I have managed to track down. Left out were those instances that were repetitive of points made better elsewhere or that were so brief and unrevealing that they added little to our sense of the man and his work. I know that there must be correspondence out there that I have failed to locate and I am also aware of some elusive runs of letters that people feel sure they possess but have been unable to find for me. In some cases recipients preferred to keep correspondence private. Doubtless more letters will emerge after the publication of this volume that will help future biographers and scholars of the work to come to a still fuller picture of McGahern and his life. That said, I am aware of no long run of correspondence to which I have not had access and I am confident that the letters reproduced and annotated here give an accurate sense of the writer’s epistolary life.

McGahern’s confession to Keelan about the difficulties of writing a true letter and yet his happiness in receiving same is not surprising, for he liked to read other people’s letters. Among his favourite books were W. B. Yeats’s Letters on Poetry to Dorothy Wellesley; Franz Kafka’s Letters to Milena; and Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. The first of these he gifted to Mary Keelan during that intense friendship of 1963–64, the last to another friend of Dublin’s early 1960s, Nuala O’Faolain. So fond was McGahern of John Butler Yeats’s letters that he undertook to bring forth a new edition in 1999 for both a French and an English audience. ‘The letters’, he writes in his lively introduction, ‘have given me pleasure for many years. They can be gossipy, profound, irascible, charming, prejudiced, humorous, intelligent, naive, contradictory, passionate. They are always immediate.’3 In that introduction McGahern provides a potted history of the letters as they came to publication over the years and is amused by how much Yeats enjoyed seeing his own epistolary handiwork in print, quoting the old man on the subject: ‘I have a copy which I constantly read and find very illuminating. Swift confesses to something of the sort with his own composition.’4

We can say with near certainty that McGahern did not feel about his own letters as Yeats or Dean Swift did about theirs. One never gets the sense when one reads a McGahern letter that it was composed with permanence or posterity in mind. His letters, while often spasmodically beautiful, are not self-conscious works of art. But one might argue that the correspondence, because he is not writing self-consciously, is all the more truthful and revealing. There is a noticeable change in handwriting from the late 1950s cursive, careful script still under the sway of schooldays and teacher training, to the later small, jagged block letters that populate the great majority of his correspondence. As early as 1961, McGahern’s penchant for handwriting over typing was irritating his fellow Irish writer John Montague as the two of them exchanged letters on the subject of a proposed anthology of new Irish writing: ‘Your handwriting is so bad that it brings me comfort since mine (which people have always found terrible) couldn’t come within an ass’s roar of yours for incomprehensibility. You also write on both sides of light paper, thus ensuring that the script on one side is blotted out by the other. You should buy a typewriter.’5 Only a small number of McGahern’s letters are, in fact, typed, and those that are tend to be of a businesslike nature in communication with publishers and agents about contracts or royalties. Very occasionally, in transcribing the work, a word has proved illegible and is marked so by me in square brackets; when McGahern makes an obvious error in leaving out a word, I have inserted that word in square brackets, unless its absence reflects his personal style of speech and prose. I have let oddities of spelling and punctuation stand unremarked. McGahern never felt confident enough to type his own handwritten manuscripts. Prior to the later 1960s and meeting Madeline, he paid for professional transcription of his work. Much of the £100 he won in 1962 as the AE Memorial Award for sections of the still incomplete debut novel that was to become The Barracks in 1963, for instance, was absorbed in paying for half a dozen copies of the work to be typed.

McGahern, contrary to certain received views of him as an isolated gentleman farmer, or what he calls in one note composed towards the end of his life ‘the myth of Farmer John’, travelled a good deal and lived at many addresses in Ireland, England, the United States and France.6 This facet is especially true up to the mid-1970s when he and Madeline moved to a modest cottage in Foxfield, Co. Leitrim. ‘Madeline, as well as I,’ he writes to an editor at the American publisher Alfred A. Knopf in October 1975, ‘is tired of climbing other people’s stairs. It’s eleven years of having no place now.’7 For most letters McGahern supplies an address, for some I have had to rely on postmarks, and for others I have made educated guesses based on dates and contexts. Where the address is not provided, I have used square brackets around what seems the likeliest place of origin. The use of such brackets has also been my practice when estimating dates of composition, although there are a few occasions where the guess has to be as vague – as in the case, for instance, for many of John’s letters to his sister Dympna from the late 1950s to early 1960s – as just supplying a year rather than a day or a date.

In terms of my footnoting practice, a short biography of each correspondent is supplied for the first letter or email. Where possible, these biographies include year of birth and, where applicable, year of death. When a question arises in a letter that appears not to be addressed in the footnote, the reader can assume that it was not possible to supply an answer despite my best efforts. The only alternative to this method would have been to footnote ‘unknown’ whenever I had failed to track down fully the source of the piece of information or the answer to some question that arose within the letter. Very occasionally I have chosen to do this if I thought it helpful to the reader. I have kept editorial comment – especially as it relates to the interplay between the life and the work – to a minimum. So, for instance, I have not found it necessary to comment on the ways in which McGahern’s December 1957 letter to Tony Swift breaks into second person singular narrative to describe first person action, just as occurs at length in The Dark. Usually I have thought it best for readers to come to those sorts of conclusions themselves. But there are occasions where I felt it better to give some guidance and provide links between biography and fiction, such as in one letter to Dympna of December 1964 when he describes enthusiastically a particular chair he has seen in St Petersburg – a chair that reappears in an early draft of ‘My Love, My Umbrella’.

What would McGahern have thought about an edition of his letters being made public? Given his general suspicion of literary biographies, I think we can surmise that he would have disliked the idea. He was resistant to permitting the reader access to the private workings of the author’s mind and sensibility. ‘Sometimes I am uneasy when I remember all the letters hanging about your flat,’ he writes to Patrick Gregory, his first American editor.8 Gregory reassures him that there is no cause for concern, though it has been much to the benefit of this project that Gregory, in fact, carefully kept much of this correspondence and donated it to the National University of Ireland Galway after McGahern’s death and where it can be consulted today.

One 1976 letter to Madeline about his efforts to complete the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.8.2021 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Briefe / Tagebücher |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | amongst women • BBC • Booker Prize • Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres • Irish Times Award • Prix Etrangère Ecureuil • Society of Authors Travelling Scholarship |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-32667-6 / 0571326676 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-32667-9 / 9780571326679 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich