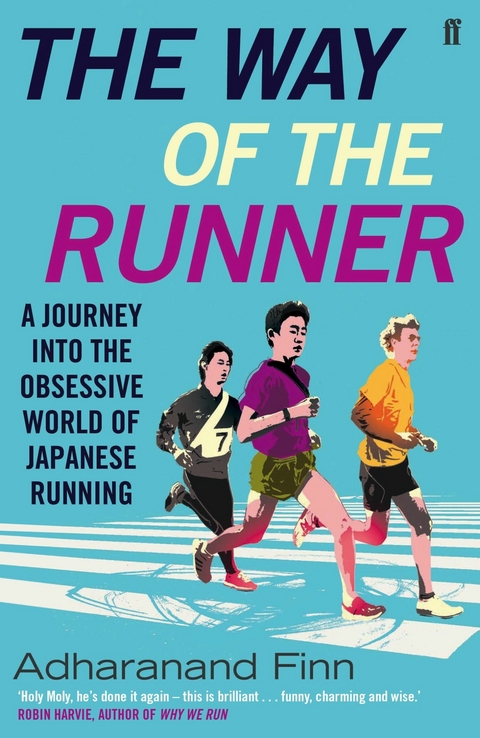

Way of the Runner (eBook)

304 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-30318-2 (ISBN)

Adharanand Finn is the author of Running with the Kenyans (2012), The Way of the Runner (2015) and The Rise of the Ultra Runners (2019). The first of these was the Sunday Times Sports Book of the Year, won Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards and was shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book Award. He is a journalist at the Guardian and also writes regularly for the Financial Times, the Independent, Runner's World, Men's Health and many others.

Welcome to Japan, the most running-obsessed nation on earth, where: a long-distance relay race is the country's biggest annual sporting event; companies sponsor their own running teams, paying the athletes like employees; and marathon monks run a thousand marathons in a thousand days to reach spiritual enlightenment. Adharanand Finn - award-winning author of Running with the Kenyans - moved to Japan to discover more about this unique running culture and what it might teach us about the sport and about Japan. As an amateur runner about to turn forty, he also hoped find out whether the Japanese approach to training might help him keep improving. What he learned - about competition, about team work, about beating your personal bests, about form and about himself - will fascinate anyone who is keen to explore why we run, and how we might do it better.

Adharanand Finn is the author of Running with the Kenyans, which was the Sunday Times Sports Book of the Year, won Best New Writer at the British Sports Book Awards, and shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book Award. He is an editor at the Guardian and a freelance journalist. He is also a former junior cross-country runner and now competes for Torbay AC in Devon, where he and his family usually live. Follow him on @adharanand.

I enter through the revolving doors of the Tower Hotel, by the river Thames in London. It’s a warm April morning just a few days before the 2013 London marathon. My legs feel strong and bouncy. I’m ready to race and I can sense the quiet buzz of anticipation here at the elite athletes’ hotel.

Just inside the door, by a curving marble staircase, a small group of people are in discussion. I recognise one of them. It’s Steve Cram, my childhood running hero. He’s older now, of course, his hair shorter, flatter than in his heyday, but the same man I used to watch on television many years ago, his yellow vest whizzing around the track in pursuit of world records. I walk on, into the lobby.

As I stand there, runners walk by. Two Kenyan women in large puffer jackets wander past, their matchstick legs looking as though they might buckle under the weight of the jackets. They speak to each other so quietly it’s hard to know if they are actually talking. By the reception desk, two Dutchmen with big laughs are chatting to a man in sunglasses with his hood up. It’s only when I hear his voice that I realise it’s Mo Farah.

A lot has happened in the twelve years since I stood hungover by that school wall in Japan. Somewhere along the line I started running again. Slowly, at first. I ran my first 10K race in 47 minutes. For two years it remained my best time. But gradually I began to take things more seriously, joining a running club, heading out for longer and longer runs. Then I went to live in Kenya, to train with the great Kalenjin runners of the Rift Valley. I went partly to improve my running, but also I went on a mission to understand and unravel the mystery that surrounds these great runners. I wanted to know who they were, what they did, and what moved them. When I came back I wrote the book Running with the Kenyans: Discovering the Secrets of the Fastest People on Earth.

In a few days a battle will rage between a group of Kenyans and Ethiopians to win the most prestigious city marathon in the world. I’ll be running too, somewhere among the sweating throng of people strung out along the streets behind them. I’m hoping to beat my best time and run under 2 hours 50 minutes. I’ve trained hard for it, eaten the right food, bought the right kit. But today, as I stand in the Tower Hotel lobby, it’s neither me nor the Kenyans I’m interested in. Today, I’m looking for the Japanese.

*

Something is going on in Japan. From the outside, it’s easy to miss. Virtually every big road race around the world is won by a seemingly endless succession of superfast Kenyans and Ethiopians. No one else gets a look in.

But on one small group of islands in east Asia, they’re at least putting up a fight. In 2013, the year in which our story is set, only six of the hundred fastest marathon runners in the world were not from Africa. Five of those six were from Japan.*

In the women’s marathon, eleven of the top hundred runners in 2013 were from Japan. Again, that was clearly the third highest number after Kenya and Ethiopia.

In the same year, the year following the 2012 London Olympics, not a single British runner managed to complete a marathon in less than 2 hours 15 minutes. In the USA, twelve men ran under that time. Yet in Japan, a nation with less than half the population of the US, the figure was more than four times higher, with fifty-two Japanese men running a marathon in under 2:15.

And in the half-marathon, Japan is even stronger. On the morning of 17 November 2013, at a half-marathon in Ageo, a small city squashed in among the sprawling northern suburbs of Tokyo, hundreds of university students lined up hoping to impress their team coaches ahead of the important Hakone ekiden in January. Ageo is one of the main try-out races for the teams, but still many of the best university runners were missing that day, while virtually all Japan’s hundreds of professional road-runners were also absent. Yet, watching the end of the race on blurry YouTube footage† something amazing unfolds.

The winner, getting his nose ahead in a five-way sprint finish, crosses the line in 62 minutes 36 seconds. This is pretty fast, but the real story is what happens next. Usually, if you watch a top-level race anywhere else in the world, the first few runners will finish with clear daylight behind them. Often they have time to get changed, do interviews, have a drink and do a warm-down before more than a handful of other runners have crossed the line. But not here. The amazing thing is how they just keep coming. Runner after runner, one behind the other, crossing the line, sometimes in big groups, turning and bowing to the track, some collapsing on their knees. All of them checking their watches. All of them running fast.

In the final breakdown, eighteen runners finished the race in under 63 minutes that morning. In one race. In the whole of 2013, only one British runner ran a half-marathon that fast. Only twenty-one US runners, in the whole year, managed it.

The student finishing way down in 100th position in Ageo still completed the course in 64 minutes 49 seconds. That would have ranked him in eighth position overall in the UK in 2013. In many other European countries he would have been the national champion. That’s a remarkable depth of running talent.

So, something is going on in Japan. My mission with this book is to find out what it is.

I’m intrigued not only as a writer, but also as a runner. After my six months in Kenya I returned to England and broke all of my personal best times, from 5K to the marathon. For six months I was on one long, jaunty upswing, breaking ten PBs in a row.

But in the last two years I haven’t gone any faster. I’m about to turn forty, and I can’t help thinking, is this it? Have I passed my peak? Is it time to give up on the thrill ride of chasing personal bests, the buzz of breaking new ground, and instead begin on that calmer, post-peak journey of simply enjoying running? In some ways I look forward to those days, when running becomes a gentler pursuit, less determined and obsessive, when I’ll simply enjoy the sensation of my heart pounding, and the feel of the cold, fresh wind on my face without worrying about training plans and tapering and stopwatches.

But the competitive gremlin in my gut wants one last hurrah. Surely 2:55 is not going to be my final marathon time? Seventy-eight minutes for the half-marathon? It’s OK, but I’m sure I can go faster. I learnt much in Kenya, but perhaps the lessons in Japan will be different. Perhaps I can learn something new from those swarms of talented half-marathon runners in that fuzzy YouTube footage, something to push me on that one, final step further. My journey to find out begins here in the Tower Hotel in London.

*

A man is walking towards me, his white teeth gleaming across the lobby. It’s Brendan Reilly. Everyone I’ve spoken to about running in Japan has mentioned his name. He seems to be the linchpin for everything, the gateway between Japan’s insular running world and the outside. He has arranged a three-way meeting with me and a respected Japanese coach, Tadasu Kawano. Kawano trains the Otsuka Pharmaceutical ekiden team, based in the city of Tokushima on the island of Shikoku. A couple of his athletes are running the London marathon in a few days.

‘Hello,’ says Reilly. ‘How are you?’ A firm, American handshake.

He takes me to sit down at a table in the hotel cafe. Kawano is there, waiting. An elderly man, he looks tired, leaning over to one side. He nods his hello as I sit down.

‘Hajimemashite,’ I say in my best Japanese. Pleased to meet you. He smiles. ‘Ah, hajimemashite,’ he says, as though it’s a game. But that’s as far as we’re going. My full Japanese repertoire is already used up, so we switch to English, with Reilly translating.

‘I want to join an ekiden team,’ I say. ‘Can you help?’

Japan is unique in offering long-distance runners a salary to join a team. Big companies such as Honda, Konica Minolta and Toyota keep teams of professional road-runners who live and train together and compete in ekiden races. My plan is to join one. Not as a competitive runner – I’m too slow for that – but to embed myself with a team, like a war reporter embedded in a military unit. It seems a good way to get close enough to the athletes to understand how it all works. To learn the secrets of Japanese running. Although finding a team to take me on is proving more difficult than I’d imagined.

I’ve read that these corporate road-runners are huge sports stars in Japan. In fact, it was after reading an article written by Reilly, in Running Times magazine in the US, that I first realised what a big deal running was in Japan.

‘Chat with your taxi driver or sushi chef on a night out in most Japanese cities,’ he wrote, ‘and it becomes apparent that Yuko Arimori, Naoko Takahashi and Mizuki Noguchi are national icons even among the sedentary. Likewise, the employees of the corporate sponsors of distance teams are as fervent as fans of the Beautiful Game. The stands at a national ekiden relay championship are a rainbow of corporate colors and logos, as employees garbed in their company hues give raucous support to their runners.’

He goes on: ‘In Japan, live broadcasts of marathons and ekiden events, which carry all the expert analysis and technical quality given the NFL here at home [in the US], garner staggering numbers. While US marathon broadcasts rarely creep above 1% ratings, in Japan a 10% rating...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.3.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Leichtathletik / Turnen | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Schlagworte | born to run • Japan • Marathon • mo farah • paula radcliffe • Running • running with the kenyans |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-30318-8 / 0571303188 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-30318-2 / 9780571303182 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich