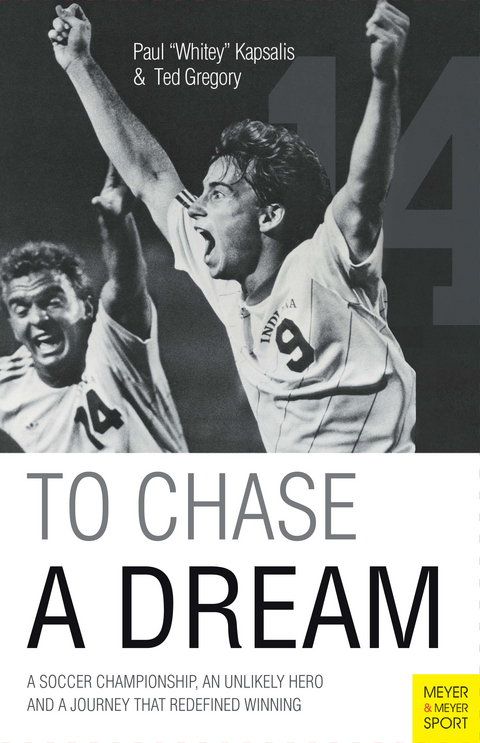

To Chase a Dream (eBook)

232 Seiten

Meyer & Meyer (Verlag)

978-1-78255-723-4 (ISBN)

Paul 'Whitey' Kapsalis is a Sales Representative in the Apparel Industry in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he has successfully built a loyal and lucrative customer base. Previously, Paul owned and built a soccer specialty retail business into the Number 1 Soccer Specialty Store in the country in 2004 (as awarded by US Soccer). Recognized in the Indianapolis Business Journal's 'Forty under 40' list for positive contributions, he also won the Indiana Youth Soccer Presidents Award in 2010. In that same year, he won the Indiana Sports Corporation Volunteer of the Year Award. Paul is a Youth Minister and Eucharistic Minister and also serves as chairman of the Bigelow-Brand Charity Advisory Board of the Pancreatic Cyst & Cancer Early Detection Center. He's a soccer coach who, through words and actions, inspires participants to reach for their goals every day. Paul, Sherri and their three children live near Indianapolis, Indiana. Ted Gregory is a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter at the Chicago Tribune. In addition to his newspaper work, Ted is co-author of Our Black Year, a nonfiction account of an African-American family's effort to patronize black-owned businesses exclusively for one year. He lives near Chicago, Illinois, with his wife and children.

Paul "Whitey" Kapsalis is a Sales Representative in the Apparel Industry in Indianapolis, Indiana, where he has successfully built a loyal and lucrative customer base. Previously, Paul owned and built a soccer specialty retail business into the Number 1 Soccer Specialty Store in the country in 2004 (as awarded by US Soccer). Recognized in the Indianapolis Business Journal's "Forty under 40" list for positive contributions, he also won the Indiana Youth Soccer Presidents Award in 2010. In that same year, he won the Indiana Sports Corporation Volunteer of the Year Award. Paul is a Youth Minister and Eucharistic Minister and also serves as chairman of the Bigelow-Brand Charity Advisory Board of the Pancreatic Cyst & Cancer Early Detection Center. He's a soccer coach who, through words and actions, inspires participants to reach for their goals every day. Paul, Sherri and their three children live near Indianapolis, Indiana. Ted Gregory is a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter at the Chicago Tribune. In addition to his newspaper work, Ted is co-author of Our Black Year, a nonfiction account of an African-American family's effort to patronize black-owned businesses exclusively for one year. He lives near Chicago, Illinois, with his wife and children.

Chapter 1:

THE NEW FAMILY PASTIME

Me, Deanne, Pete, Dean and Dan get ready for our first season in Edina, MN.

Baseball was supposed to be my passion.

It certainly was our family passion. We’re Chicago Cubs fans. But, the Cubs being what they are, perennial “lovable losers,” maybe it was divine mercy that directed me somewhere else. Maybe it was dumb luck, or maybe it was for another reason I wouldn’t understand until almost two decades later.

But, at age 5, soccer became my game. Our family moved for the second time in what would be five times to accommodate my dad’s career, a move that dropped all of us in suburban St. Louis, where my dad looked to register his kids in a baseball league.

In our family of four boys and a girl, sports always were a big part of our lives, and I was the middle child, which meant I was right in the middle of everything. We had a lot of energy and sports weren’t only a way to burn off all that energy. They also were the vehicle our parents used to get us kids acclimated to a new town and to make friends in those new towns. It became our routine. We’d move in and my dad would sign us up for baseball, often before we’d finished unpacking. It was pretty effective, and I guess it was lucky for my parents that all of us kids loved sports.

But this time, in moving to Collinsville, Illinois, nine miles from St. Louis, my dad was about to be thrown a curve ball. He drove to a park where youth sports volunteers had set up card tables. It was the fall, and he asked what sports they offered. They said soccer. He said what else?

My dad’s only recollection of soccer was from his high school days, back in the 1950s at Amundsen High School on Chicago’s North Side. “Foreigners” used to play it around the school fields, and my dad and his friends poked fun at them because they wore short pants and communicated in foreign languages. Andy Kapsalis was a great athlete who loved basketball, baseball, and football. Way back then, in his youth, and as he stood there at the soccer league registration table in Collinsville, he thought, what kind of sport doesn’t involve catching the ball?

He would, of course, change his mind completely in a few weeks, going on to help establish youth soccer leagues, helping my mom create a highly successful soccer retail business, and becoming one very enthusiastic soccer fan. But, at that moment, in Collinsville, kids’ baseball leagues were six months away, and he wanted his kids to play an organized team game immediately.

He figured soccer was a team sport in which we could burn off all that energy and make friends. He registered his kids right there. Like many of my dad’s instincts, he was right.

Almost immediately, my mom went out and bought a soccer ball. We inflated it, tossed it in the back yard and started kicking. We didn’t know the rules. My parents didn’t know the rules, but we knew how to kick a ball and after a few days, we set up a crude soccer pitch in our back yard, using t-shirts and cones — whatever we could find — to mark goals. Being brothers, we pounded the snot out of each other and, playing every day, slowly became decent players. My dad even joined us on weekends and one Sunday, broke his ankle. Even that wouldn’t dampen his love for the game.

We also started playing hockey, but soccer was my first sport. I remember wanting to play all the time, totally absorbing everything coaches were dishing out. Love at first kick. The running, being outdoors on beautiful green grass, the high-level of teamwork, the grace, the power, the struggle, the competition — all of it resonated deep inside me and brought me such joy and release. I suppose it’s the same way with a lot of folks when they find their calling: musicians and painters, writers and scientists, teachers and mathematicians. They must feel it in their marrow almost instantly.

I made the local tykes all-star team and got to play in Busch Stadium before the St. Louis Stars, the city’s professional soccer team, played a game. There I was, a squirt of five years old, walking in that stadium. The thrill was indescribable. Then we walked through the dugout on the field and a very familiar emotion flared in me: nervousness, anxiety bordering on fear; knowing deep inside that I had to give it everything I had to compete. That feeling was something that stayed with me throughout my playing career, and, looking back, it may have helped as much as it hurt.

The giant stadium engulfed me; overwhelmed all of us, really. We must have looked like ants; sure felt like it. But that didn’t matter to me or, I’d guess, to any of the other kids. When the game ended 1-1, we were greeted and congratulated by St. Louis Stars players. That was it for me. I was hooked totally and was going to chase soccer for as long as I could.

Two years later, my short career looked finished. My dad got transferred and moved us again, this time to Edina, Minnesota, a community with a lot going for it, but no youth soccer league. We could have gone back to baseball, but my parents saw the spark that soccer had ignited in their kids. So, mom and dad made a league of their own. The Edina Soccer Association was launched with 16 teams, allowing all five of us Kapsalis kids to play. Establishing that league made my parents look like prophets. They got out in front of what would be the wave of youth soccer popularity sweeping across the U.S. That’s also where I got my nickname, Whitey. My dad gave it to me. Of all my parents’ children, I was the only one who didn’t have dark brown hair. Guess what color mine was? That’s right, an almost white blond. We’re still trying to figure out that one.

Four years later, we moved again, this time to Birmingham, Michigan, near Detroit, which did have a youth soccer league, and my parents wanted to register us. But, we arrived in the winter so my dad arranged for us to join the local hockey league.

The problem was that the hockey season had started a few weeks before we showed up. I can remember when my dad was helping me get dressed in the locker room for my first game. I was playing in an age group a year older and could hear some of the guys muttering to themselves about this new kid. I was much smaller than everybody else, my helmet barely visible above the boards, and in this new environment, felt a little like an invader, an unwanted visitor who the other guys thought was going to upset team chemistry. I hated it and as I trudged toward the rink, I told my dad I didn’t want to go out there, didn’t want to sit on the bench, and certainly didn’t want to get on the ice with these guys. I was really intimidated.

“You’ll be fine once you get on the ice,” he told me. “You’ve got nothing to lose. Just try it today. If after the game, you don’t like it, we’re done. Over. Finished. You don’t have to come back. No big deal. But you’ve got your skates on, all the gear, just get out there and try it.”

He made a pretty persuasive argument. So, I clonked ahead on my own and those first few minutes on the bench, I ignored all the muttering from my teammates, but I was scared. No other way to say it. My dad joined my mom in the stands and they later told me that when I took the ice, all the parents were saying things like, “What’s that little guy doing out there? He’s going to get hurt. This is ridiculous. What’s the coach thinking?” He and my mom sat there, steaming but silent.

I don’t really remember my mindset when I pushed onto the ice. I’m sure I had that fear and anxiety, but I also was one competitive little guy, and I knew how to play hockey. Heck, I’d been playing in Minnesota, where it’s religion, for about four years.

Well, I scored a goal in the first couple of minutes. Funny how that changed everybody’s perspective. From that point on, when I took the ice, the parents started saying, “Here he comes, our secret weapon.” Suddenly, my teammates rallied around me like I was their little brother. My mom says that was one of the first times I demonstrated the ability to draw people together, my first moment of leadership. I’m not sure of all that, but I had a whole lot of fun playing hockey with those guys, and I think they felt the same about me. That’s all that really mattered to me then.

The other thing that one moment did was teach me to confront my fears. I’m so grateful my dad gave me that extra nudge to take the ice. I overcame all the uncertainty and, when I proved I was capable, my confidence grew. I knew I could handle more than I had thought I could, something I think all of us need to realize about ourselves. Those first few moments on that hockey team, as imperceptible as it was to everybody else, were enormously significant in my life.

And, the quiet confidence that experience created in me transferred to soccer in Birmingham, where our passion for the game deepened and became nearly all-consuming. Weather permitting, we played every day after school in our back yard or at a local park, like we had at our earlier homes.

A couple years after we moved there, Detroit entered the professional North American Soccer League, establishing the Detroit Express in about 1978, and my family became huge fans. All of us attended every home game in the old Pontiac Silverdome. Those were some of the most fun family times I can recall.

Watching professional soccer live on a regular basis also stoked our dreams. In the back yard we’d imitate our favorite players: Keith Furphy, Trevor Francis, Alan Brazil, Dave Shelton, and a handful of others. We were big fans of Shelton. One of only three Americans on the Express roster, he played at Indiana University, a place we’d never...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.12.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Aachen |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Ballsport | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | achievement • Championship • College • collegiate soccer • erzählend • Fußball • Indiana Hoosiers • Indiana University • Inspirational • national championship • NCAA • Pete Stoyanovich • Soccer • team sport • True story • Underdog • USA |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78255-723-7 / 1782557237 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78255-723-4 / 9781782557234 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: PDF (Portable Document Format)

Mit einem festen Seitenlayout eignet sich die PDF besonders für Fachbücher mit Spalten, Tabellen und Abbildungen. Eine PDF kann auf fast allen Geräten angezeigt werden, ist aber für kleine Displays (Smartphone, eReader) nur eingeschränkt geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür einen PDF-Viewer - z.B. den Adobe Reader oder Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür einen PDF-Viewer - z.B. die kostenlose Adobe Digital Editions-App.

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich