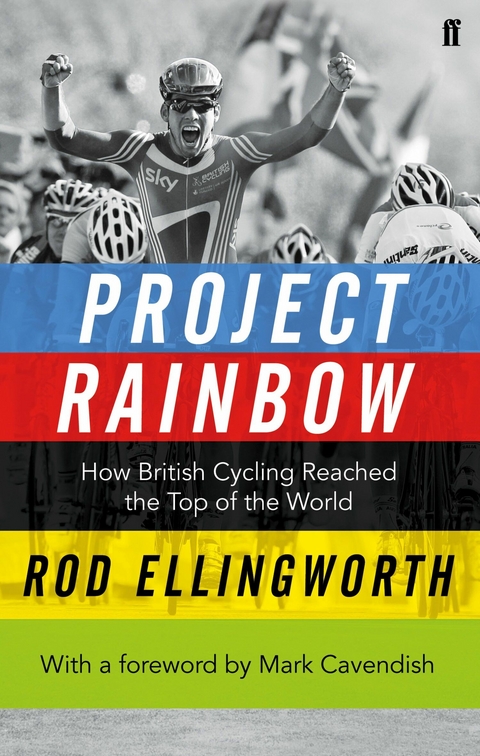

Project Rainbow (eBook)

384 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-30352-6 (ISBN)

Having represented GB from 1989 until his retirement in 2001, Rod Ellingworth founded and ran the GB Cycling Academy. Then, alongside Dave Brailsford and Fran Millar, he was instrumental in creating Team Sky in November 2008. William Fotheringham has been the Guardian's cycling correspondent since 1994. He has covered 22 Tours de France and four Olympic Games and his published work includes the best-selling biographies Put Me Back On My Bike: In Search of Tom Simpson and Merckx: Half-Man, Half-Bike. Most recently, he co-wrote Bradley Wiggins's best-selling memoir My Time.

Having represented GB from 1989 until his retirement in 2001, Rod Ellingworth founded and ran the GB Cycling Academy. Then, alongside Dave Brailsford and Fran Millar, he was instrumental in creating Team Sky in November 2008. William Fotheringham has been the Guardian's cycling correspondent since 1994. He has covered 22 Tours de France and four Olympic Games and his published work includes the best-selling biographies Put Me Back On My Bike: In Search of Tom Simpson and Merckx: Half-Man, Half-Bike. Most recently, he co-wrote Bradley Wiggins's bestselling memoir My Time.

Copenhagen, 25 September 2011

There were three of us in the Great Britain race car that day, for seven hours and seventeen laps of the circuit in Copenhagen. In the front with me was Brian Holm, Mark Cavendish’s directeur sportif at the HTC team; Diego Costa, a mechanic with Team Sky, was sitting behind us. Normally a team car in a professional bike race has a television in the back for the mechanic, as well as one in the front for the DS, but we had only one, so the thing that sticks in my mind is Diego’s hot breath down my neck as he looked over my shoulder at the screen, hour after hour, all the while clutching a pair of spare wheels in the back-seat space.

I’d thought long and hard about who to have with me in the car. Brian was there because being a directeur sportif isn’t my forte and he’s been full-time at it for over a decade in professional cycling. I had to drive the car because I was managing the team, but it made sense to have someone of his experience there. Brian is Danish but he does love Britain with a passion – that was why he had found common ground with Cav when he began working with him in his first full year as a pro. It made sense to have someone in the car in whom Cav had built so much trust over the years. Brian had won a lot more races sitting in a car directing Cav than I had, and there might be a moment when that made the difference. Plus we were in Denmark, and Brian is a national hero in his native country. Cav was proud to have him in the car. There was a personal side to this for Brian as well: I knew Cav was going to be changing teams at the end of the season; for the first time in five years they would no longer be working together.

Brian hadn’t been part of the build-up to the Worlds, but his years of experience mattered. That shone through when we were talking through the tactics for the day, about when the team would start to ride hard behind the day’s main break, whenever that happened to form. They wouldn’t start chasing from a set point whatever happened, say fifty or sixty kilometres out; they would get down to it when the break had formed and had got a certain number of minutes ahead. We discussed it with the riders: it was to be about four or five minutes, and we knew it was going to be a big group. I had been a bit uneasy with that – I didn’t want to intervene as it was the riders’ decision – so on the morning of the race, when Brian said he thought it was about right and there should be no panic, I thought, ‘Perfect.’ That kind of thing really bolsters your confidence.

And then there was Diego, an Italian, from Piacenza. I’d chosen him because although we’ve got plenty of British mechanics, he’s the best I know in the race car. You have to think about it – what’s the mechanic’s job in the car? He’s got to study the race and help the two guys sitting in the front work out which riders are in which group. That’s down to listening to the short-wave race radio. Diego speaks perfect French, Italian and Spanish, and he’d learnt English in two years. He’s very particular about his work; not a great person in a team, but good on his own. And I’ve never seen anyone as fast at getting out of the car and fixing a puncture; just being very confident about it – no panic, just gets it done. That alone could be the difference between winning and losing.

Diego was going through a rather particular time in his life. He had just got a new girlfriend and was constantly on the phone to her. So when we got in the car at the start of the race and I said, ‘OK, guys, unless there’s a major crisis, no phones now,’ he was pissed off and wouldn’t talk to me for the first two or three hours. I didn’t give a shit; he still did his job. That’s something I always do – I wouldn’t answer the phone to my wife when I’m in a race car unless it was an emergency. It’s our job to make that clear to our other halves. I remember years back I was in a race, on the radio to one of the riders, and he couldn’t hear me because someone in the car was on the phone. It makes a difference.

We’d thought about the telly as well. Chris White, the performance analyst who had been working with us since the start of the road Worlds project, had hired it and had made sure it was going to work. He’d done a load of checks around the course to see where the signal dipped in and out. So you would go under some trees and you’d know you were going to lose it. That in turn meant you didn’t start fiddling with the dials, because there was no panicking that you were going to lose the channel and how would you get it back? You’re ready for the picture to come back at a certain point, and then you’re straight back on it again. It all helps you keep calm.

We had good reason to be nervous. We’d been working towards this one day for the last three years, since I’d gone public with the idea that Great Britain could build a team with the aim of winning the elite world road race championship, the biggest one-day race in the sport, the one that rewards its winner with the right to wear the rainbow-striped jersey for the next twelve months. Britain had only won it once, with Tom Simpson back in 1965, and had never looked like winning it since. This could be our once-in-a-lifetime chance: this might be the only time in Cav’s career that he would get the flat course that suited him. The build-up hadn’t been straightforward, but we knew he was ready, and that might not happen next time. We also knew the team had bought into the idea, in a way that no British team had done since the day that Simpson won it nearly half a century ago.

The project had got under way in 2008, but it had been seven years since Mark Cavendish had first told me that he wanted to win the Worlds, back in 2004, when we started working together. It sounded unlikely then, but a few years later it had begun to look like it might be possible one day, as he’d landed his first big win – the Scheldeprijs – started his first Tour de France and won some smaller races. He’d ridden the 2007 Worlds just to get in amongst it, to feel it, to experience how the Italian and Spanish teams worked, how teams come together from their day jobs working for other outfits and have to race as a unit from scratch on that one day. That was the key to the whole project. Assembling a team for the Worlds is like English footballers playing together for their country in the World Cup after kicking the stuffing out of each other in the Premiership all season – you have to work hard to get it right.

It might not have crossed many other people’s minds, but it was clear to us back then that no one in cycling was faster than Mark Cavendish – and that made life a lot easier when it came to winning a one-day race like the Worlds – plus we knew the riders had the engines to ride as a unit and keep the race together for him on a flat course. I felt we had the talent, so the question was: how do we do it? It helped that the bulk of those cyclists in the team that day had come up through the Great Britain academy which I had founded – riders like Ian Stannard, Geraint Thomas, Cav himself, of course – so they all understood how I worked and how Cav operated. And the older guys like Steve Cummings, Bradley Wiggins, Jeremy Hunt and David Millar were all smart and had always got the picture too.

Before the start of a one-day race there is a lottery for the car’s position in the convoy; we had been given a really bad draw – nineteenth – and were supposed to be sharing the car with the Irish, although Great Britain were in the top ten in the world rankings. I said there was no way we were going to share with Ireland if we were out to win the Worlds; I’ve got nothing against the Irish – I am half Irish myself – it was the pure principle of it. So Dave Brailsford, the GB Performance Director, protested against it, and did a bloody good job. He managed to get us moved up the order, but we were still well outside the first ten, which meant that if anyone needed a wheel change or a fresh bike, it would take us that little bit longer to get to them. For most of the race that wouldn’t matter, but at the end it could cost us everything.

We knew that even if Cav had a problem right up to the last five or six kilometres, he would still be on for the win; he could crash or puncture, and we could still bring him back, but if he did have a problem after that, there would be no use being car eleven or twelve. We’d have to be right there behind the bunch if something happened. It had taken a bit of planning to get round that one, but we had worked out that with a bit of front we would be able to do at least half a lap as car number one in the convoy. This was where Brian had come into his own. Just before the end of the lap there was a right-hand corner, then the finish straight, and after that the road narrowed to go past the feed zone; no cars would be doing any overtaking there, and then there was a fast section where the peloton was flat out and the cars would all be split up.

Brian said to me, ‘Right, when I say “Go”, you go with all guns blazing, horn blaring, making a big noise – and time it so that the second you hit that right-hand corner before the finish straight, you’re car number one in the convoy.’ So we were flat out, screaming past the other team cars. I was hanging onto the wheel, Diego breathing down my neck all the time as he kept his eyes on the telly. And as we flew past the other team cars, everyone was looking at us, thinking, ‘What do they know that we don’t? Why are they moving up now?’

So we got to the front and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.10.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Fahrrad | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Motor- / Rad- / Flugsport | |

| Schlagworte | Bradley Wiggins • Chris Froome • Cycling • cycling book • mark cavendish • Team Ineos • Team Sky • The Manx Missile • Tour de France |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-30352-8 / 0571303528 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-30352-6 / 9780571303526 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich