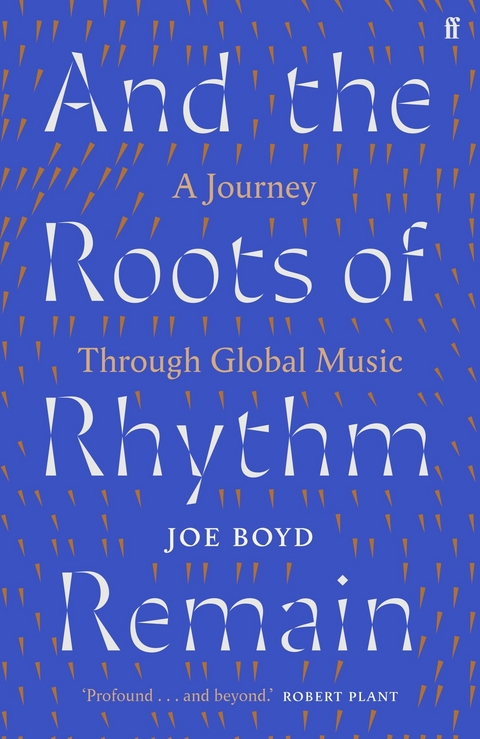

And the Roots of Rhythm Remain (eBook)

352 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-36002-4 (ISBN)

Joe Boyd is a record producer and writer, known for his memoir, White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. Artists he has produced include Pink Floyd, Nick Drake, R.E.M., Fairport Convention, ¡Cubanismo!, Toots and the Maytals, Toumani Diabaté and Taj Mahal among many over the course of a nearly sixty-year career. As a film producer, his credits include the Aretha Franklin documentary Amazing Grace, Scandal, and Jimi Hendrix.

'I doubt I'll ever read a better account of the history and sociology of popular music than this one.' Brian Eno'Profound.and beyond.' Robert PlantLegendary producer and record label boss Joe Boyd has spent a lifetime travelling the globe and immersing himself in music. He has witnessed first-hand the growing popularity of music from Africa, India, Latin America, the Caribbean and Eastern Europe since the 1960s and was one of the protagonists of the 'world music' movement of the 1980s. In this sweeping history, Boyd sets out to explore the fascinating backstories to these sounds and documents a decade of encounters with the most extraordinary musicians and producers who have altered the course of music for us all. And the Roots of Rhythm Remain shows how personalities, events and politics in places such as Havana, Lagos, Budapest, Kingston and Rio are as colourful and momentous as anything that took place in New Orleans, Harlem, Laurel Canyon or Liverpool. And, moreover, how jazz, rhythm and blues and rock 'n' roll would never have happened if it weren't for the notes and rhythms emanating from over the horizon. 'A gift to the world. Blow your mind and your speakers' Cerys Matthews'One only hopes that this will be taught in schools.' Ry Cooder

Humiliation was staring Desi Arnaz in the face. It was 1937, the opening night of his run at a Miami Beach nightclub, and despite the frilly sleeves on their shirts, the bumbling musicians Xavier Cugat had sent him couldn’t tell a clave from the cleavage at the front-row tables. The tepid applause that greeted the opening numbers had faded to near silence; he had to do something.

According to Desi’s autobiography, an image from his 1920s Cuban childhood came to him in that moment. He was on a reviewing stand beside his father, the mayor of Santiago, watching the carnival street bands known as comparsas parade past. They danced in a line, conguero in the lead and everyone following his rhythm. Arnaz’s problem-solving brain would one day make him the first TV star to own syndication rights to his own hit show and thus one of the richest men in Hollywood. That night, it told him to grab a conga drum, start singing an Afro-Cuban chant and invite the prettiest girl from those front tables to join on behind, hands on his hips; as more and more patrons fell into line, he circled the club – all the while dancing to Latin music’s simplest beat – then led them out onto the sidewalk, startling Collins Avenue traffic as they thrust out a hip or a leg on the final stroke of that 1–2–3–4–cong-Á.

The next night the club was packed. Desi’s conga line became the talk of Miami, then the talk of New York, and finally, the talk of Hollywood. He was on his way, the latest Latin star to light up US show business in the years before World War Two. Through the soft-focus lens of Desi’s memoir, the Santiago carnival seems like a Cuban version of a Trinidad steel-band parade or a glittering Rio de Janeiro samba competition. But it wasn’t like that at all.

Standing beside them on the reviewing stand that day was Alfonso Menencier, the Afro-Cuban ward heeler who delivered the Black vote. He wore an immaculate white suit and straw boater, held a silver-topped cane and looked ill at ease. The barefoot, half-naked bodies passing before them were an uncomfortable reminder of the four short decades since slavery had been abolished in Cuba, of how blockade-running ships had continued to bring human contraband from Africa until the last minute, and that the conga line had originated in the chanting of slaves chained single-file as they were marched to the cane fields, where life expectancy was less than a decade.

These parades went back centuries to Kings’ Day and pre-Lenten celebrations, when slaves were allowed a fleeting respite from the killing fields. Some onlookers would throw coins and cheer, while others recoiled from something they found ‘savage’ or ‘barbaric’. Before Emancipation in 1886, White Cubans could rest assured that the next day drummers and dancers would be back where they belonged, in the fields and barracones. Modern notions, that these shabbily dressed and very Black revellers were actually fellow Cubans and that some twenties intellectuals were making the case that this so-very-African music represented a national culture, made many Whites (as well as aspirational Afro-Cubans) uncomfortable.

No one was more uncomfortable than Desidero Arnaz Sr; in 1925, he banned the conga lines, describing his son’s future meal ticket as ‘full of improper contortions1 and immoral gestures that do not belong to the culture of [Santiago] … [E]pileptic, ragged and semi-naked crowds run through the streets … they disrespect society, offend the morals, cause a bad opinion of our customs, lower us in the eyes of foreigners, and, most gravely, contaminate by example the minors … who are carried away by the heat of the display … engaging in frenetic competitions of bodily flexibility in those shameful, wanton tournaments.’ Another prohibition issued by the mayor forbade the use of carnival masks. The idea that Whites in disguise – women, for example – could join the crowds dancing in the streets … well, the possibilities didn’t bear thinking about.

In a photograph of Machito and His Afro-Cuban All-Stars onstage in New York in the early 1940s, a painting of a conguero looms over them. He’s huge, of indeterminate race, with bulging biceps, his hands poised over the head of a phallic-looking conga drum held by a strap at his waist, a precursor of the rock hero with guitar-neck erect in note-bending solo.

By 1937, the conga drum had already entered the zeitgeist, Cuban revues having popularised it in Paris and London. Desi’s role as Xavier Cugat’s protégé resulted from the bandleader’s search for a good-looking White guy who could both play it and sing. Like Sam Phillips in Memphis fifteen years later, who realised that finding a handsome cracker who could sing rhythm and blues would make him a fortune, Cugat sensed that anglophones were ready for someone sexy but safe to lead them onto the dancefloor and show them how to shake their asses like a Cuban.

Across the Florida Straits, the island had bowed to tourist pressure and reinstated the comparsas. Time and again, we see local culture reviled and repressed by an insecure bourgeoisie but embraced by outsiders. Grudgingly (and often avariciously), guardians of national culture admit that, well, if foreigners like it so much, there might be something there whose value they failed to recognise. In Cuba’s case, this meant drums. As bars and nightclubs filled with Americans looking for somewhere to drink, gamble and shed their inhibitions, it made sense to bring back the carnival in a more glamorous Rio/Trinidad mode, with formal competitions, cleaned-up costumes and strict policing to make sure things didn’t get out of hand.

One figure dominated the Havana parades of the late 1930s. Wearing a white tuxedo and sporting a top hat, conga drum strapped on, chanting Yorùbá and Abakuá ritual songs and playing complex rhythms, was Desi’s opposite, the Blackest, most skilful conguero of them all, Chano Pozo.

While Arnaz’s maternal grandfather had founded Bacardi, Pozo was born in a Havana slum. When his mother died, his father took up with Natalia, who already had a son, Félix Chappottín, the future revolutionary of Afro-Cuban trumpet. Their solar or tenement was called ‘El Africa’ and it was as easy to fall into a life of crime there as it was to absorb music. Perhaps it was Chano’s good fortune to be arrested at fifteen and spend a few formative years in a young offenders’ institution where he learned to be charming when it suited. After his release, the owner of El País took a shine to him and gave him newspapers to sell. Soon Pozo was at the heart of the revived carnival scene, the most powerful drummer and loudest singer around, moving from comparsa to comparsa, whichever offered the most money. After falling for a dancer with Los Dandys, he settled on them, chanting ‘I hear a drum, Mama, they’re calling me! Yes, yes, it’s Los Dandys!’2 so it could be heard for blocks around.

Like Desi, Chano adored women and had a powerful effect on them. He combined menial jobs – shining shoes, selling papers – with a strutting, idle life, wandering through the solares looking for trouble, usually in the form of angry husbands. He liked the fight game and joined World Featherweight Champion Kid Chocolate’s entourage. Pozo became as street-famous as soneros (son singers) of legend, such as Mulenze. Even after starting to make real money, he remained in El Africa, sauntering out to the communal sink in the late morning in a red silk bathrobe, his gold Cadillac parked in front.

Tourists loved the drum; Afro-Cuban percussion, chant and mockritual dancing became a featured attraction at Havana’s hottest nightclubs. Impresarios conjured up themed shows; Chano starred in Tambó en negro mayor and Batamu (which means ‘drum festival’ in Yorùbá). In the latter he shared the stage with Rita Montaner, a sepia-skinned operetta star who had turned her back on that world to become an interpreter – and champion – of Afro-Cuban music. She took Chano under her wing, convinced of his greatness.

A Black Cuban would struggle to succeed in those days without help from light-skinned friends, sponsors, mentors or lovers. After Rita and the El País publisher came Amado Trinidad, head of the island-spanning RHC Cadena radio network. He set Chano up with a shoe-shine stand in the station lobby, where he would sing and play his conga, joining conjuntos and orquestas on air, probing the possibilities of blending his powerful drumming with dance bands. But his most important ally would prove to be an old friend from the solares who returned to Havana in 1937 like a prodigal son.

Miguelito Valdés had grown up on those same street corners. As kids, he and Chano would hustle coins, Miguelito chanting in Abakuá as Chano played the conga. But Valdés was an anomaly in this world, where one of the defining...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Pop / Rock |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-36002-5 / 0571360025 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-36002-4 / 9780571360024 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 12,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich