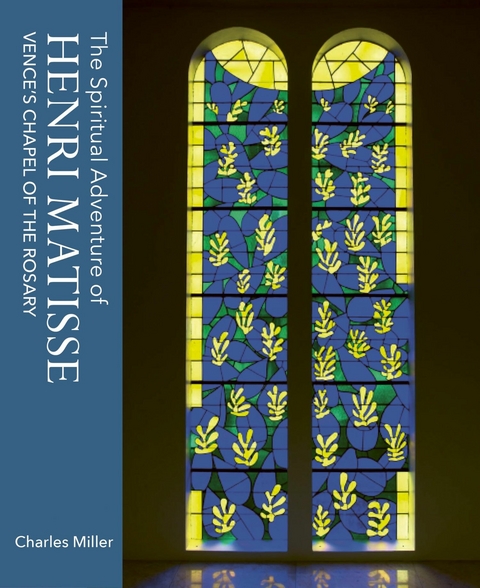

Spiritual Adventure of Henri Matisse (eBook)

232 Seiten

Unicorn (Verlag)

978-1-916846-51-7 (ISBN)

Charles Miller, an American by birth, read Classics and received his doctorate in theology from Oxford University. He has taught theology, church history and spirituality in the USA, the UK and Russia. Ecumenical interests have shaped his intellectual world and guided his life-long interest in the plastic arts and the theology of beauty. He currently serves in the Diocese of Oxford as Team Rector of the Parish of Abingdon-on-Thames.

Henri Matisse described the Chapel of the Rosary, the chief labour of his final years, as the 'gathering together' of his lifetime's work. Although widely known as 'Matisse's Chapel', the building's remarkable 'modern' design and decoration emerged from a surprising friendship and artistic engagement with a group of Dominican sisters and brothers keen to see the Church embrace 'Modern Art' and modern artists. With the advantage of hitherto unexplored archive and printed materials this study highlights that mutual encounter and explores how their shared artistic adventure became for Matisse himself an opportunity to express his 'religious' vision of art and to rediscover his natal Catholic Faith in its post-war avant-garde form.

‘Can the artist go to the sacred if the sacred does not come to him?’

PÈRE JOSEPH PICHARD, co-founder of L’Art sacré (L’Art sácre, April/May, 1947, 105)

In his vast apartment above Nice in the heights of Cimiez in 1953, during what would be his last Christmas, Henri Matisse received a letter from Paris:

This Christmas Eve I am thinking of you a good deal and of all the joy which you have given me over these past few years. Yet here it is a whole year now since I have seen you. And how I have missed that! So let me express to you again, while hoping soon to tread the way to Cimiez, all my thanks for the past and all my best wishes for Christmas and the New Year.

Then he added as a postscript: ‘I’m not faring too badly – and you see, I’m able to write.’ It was the last of many letters that the Dominican friar père Marie-Alain Couturier wrote to the artist. He had been hospitalized in Paris since May and was partially paralysed when he wrote it. Père Couturier, though only 57, died six weeks later from complications related to myasthénie and paralysis.1

0.3 View of the chapel’s south side; photo Alamy.

With père Couturier’s final letter and subsequent death early on the morning of 9 February 1954 we begin almost where this story ends, since his death brought to a close a surprising and remarkable friendship with the artist. During the years of their collaboration on the design and construction of the Chapel of the Rosary of Our Lady in Vence a bond of respect and affection had grown. As their partnership amused, bewildered, even shocked Paris’s artistic world, so the Chapel in Vence for which they closely laboured scandalized segments of France’s Catholic Church and challenged the Holy Office in Rome. Yet together they persevered in pursuit of a shared vision, they created a 20th-century masterpiece and became friends.

‘You understand how bizarre it is when people who know what you used to think about religion see you surrounded by white robes.’

MARGUERITE DUTHUIT to her father (13 March 1952, Journal, 421)

Père Couturier, central though he was to the fulfilment of Henri Matisse’s vision for the Chapel of the Rosary, was but one of a group of personalities who were drawn into the endeavour known to posterity as ‘Matisse’s chapel’. In the pages that follow we will meet those personalities and narrate the part each of them played on behalf of the chapel project. Some of this story has been told before but in contexts and in ways that have not accounted for all of those involved and how their relationships with Henri Matisse were not just functional exercises in the creation of a ‘modern’ sacred space for a small Dominican sisterhood. A circle of friendship grew that became for each of them, and for Matisse above all, a spiritual adventure.

WHOSE ADVENTURE?

So it is the spiritual adventure of the introspective, reserved, somewhat professorial 20th-century modern master Henri Matisse that these pages chiefly aim to reveal. That means that this story is also about a key moment of evolution in the synergy between theology and aesthetics, that is, how the Christian faith can be understood and expressed in what Matisse called ‘plastique’ forms: drawing, coloured glass, fabrics, furnishings and architecture. That Matisse played the part he did shouldn’t surprise us since among the masters of modernism he was the most philosophic and adept at understanding his artistic project within the frame of a cultural and artistic tradition. Ideas and concepts quietly undergirded all of Matisse’s work, and the chapel exemplifies that in regard to Christian culture and its visual ‘language’.

From another angle, though, the prominent part Matisse played in the creation of the Chapel of the Rosary of Our Lady should surprise us. In 1933 when père Couturier master-minded the Galerie Lucy Krogh’s Première exposition d’art religieuse, nothing by Matisse was to be seen alongside works of his friends Georges Rouault, André Derain and even Pablo Picasso. Unlike other masters of French modernism such as the committed Catholic Georges Rouault, or Fernand Léger, Georges Braque and the Jewish Marc Chagall, all of whom took artistic commissions for new churches, Matisse never did.2 Indeed, apart from a few copies of religious paintings in the Louvre in his early years as a student there is no religious or overtly Christian theme or imagery in any of his oeuvres. So part of our task is to understand how ‘Matisse’s chapel’ with its very public and powerful assemblage of Christian imagery and signification came about. Why and how did Matisse rise to and meet that challenge?

0.4 Père Marie-Alain Couturier circa 1940; photo source unidentified (Archives de la Province dominicaine de France [hereafter APDF], Paris; Fonds Couturier).

‘One day I saw the Goyas in Lille; I understood then that painting can be a language.’

MATISSE to père Couturier (14 November 1950, Journal, 376)

The chapel project was Matisse’s adventure first and foremost. He could never have planned it. True, he was itching for the opportunity of a monumental commission with big decorative scope, something his native France had never yet offered him. But there is not an ounce of evidence that the chapel project came his way through anything other than by happenstance. However, that happenstance was not benign.

0.5 Père Couturier’s last letter to Matisse (‘Maitre’), 24 December, 1953 (Archives Henri Matisse [hereafter AHM], Issy-les-Moulineaux).

In fact, Matisse’s involvement arose out of misfortune. More will be said about the almost fatal illness that afflicted him in 1940–41. The life-story which then unfolded is in large measure the story of how the Chapel of the Rosary of Our Lady (‘The Chapel of the Rosary’) came to be. But the chapel, while Matisse’s adventure, involved others as well, far more than published discussions of the chapel usually reveal. So the story in the chapters that follow brings Matisse’s co-workers more vividly into the picture and gives them voice. The collection of letters and related communications between the artist and the two Dominican friars who were key partners throughout the project is probably unique in the annals of mid-century French modernism. From the pages of their La Chapelle de Vence: Journal d’une création the excitement and disappointment, the inspiration, the frustration and the sheer challenge of relationships and new perspectives come alive. We hear there the voice of the wise, experienced artist-priest Marie-Alain Couturier whom Matisse more and more relied on as both aesthetic and spiritual counsellor. We hear too the eager, sometimes doctrinaire opinions of the Dominican priest-in-training frère Louis-Bertrand Rayssiguier, just about young enough to be the artist’s grandson. Another Dominican, sœur Jacques-Marie, unsophisticated and youngest of them all, in her own testimony outside the pages of the Journal gave to Matisse’s experience before, during and after the project a warm emotional depth. To the spiritual heart of Matisse she was what Couturier and Rayssiguier were to his critical artistic sense.3 Both the young sister and the young friar were as surprised to be involved in an artistic project with Matisse as he was to be involved with them. Owing to his newly fired keen interest in art Rayssiguier was aware of Matisse and his prominence in the art world’s ‘modern movement’, but sœur Jacques-Marie hadn’t even heard of him before their connection began.

Other Dominicans, such as the Order’s saintly provincial head, père Albert-Marie Avril, and the urbane intellectual père Pie-Raymond Régamey, played their different parts. So too did the sisters in the Dominicans’ petite maison in Vence under mère Gilles-du-Coeur-Sacré. With a firm but supportive, solicitous eye over Henri Matisse and the whole project from the sisterhood’s mother house in distant Monteils (Aveyron) was their able prioress general, mère Agnès-de-Jésus. All of them have a voice as this story unfolds.

In a smaller way the chapel project also proved an adventure (perhaps not so spiritual!) for Matisse’s great artistic rival Pablo Picasso. Of all in Matisse’s circle Picasso’s astonished impatience with the chapel project was the most vociferous, at moments even crude. Yet the strength of their mutual respect and artistic dialogue was such that even Picasso found...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-916846-51-3 / 1916846513 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-916846-51-7 / 9781916846517 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 20,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich