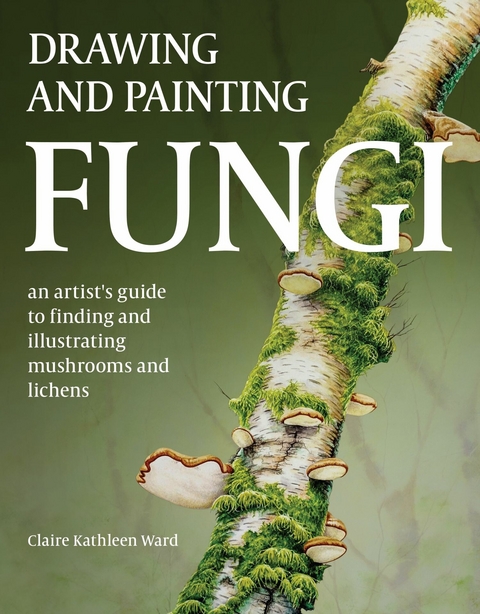

Drawing and Painting Fungi (eBook)

176 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4333-4 (ISBN)

CLAIRE KATHLEEN WARD is an award-winning nature artist and natural history illustration tutor. She hopes to encourage, promote and inspire people to become passionate about the natural world through observation and art, to conserve and protect it for the future. She is currently one of the presidents of the Society of Botanical Artists.

This comprehensive book delves into the magical and secretive world of fungi and lichens. It includes a thorough guide to the safe collection and identification of wild specimens and explains how to draw and paint them in the field and the studio, in sketchbooks and finished artworks with line, form, texture, tone, colour and composition all in mind. With over 350 illustrations, this book is an essential companion for mycophiles, artists, illustrators and journallers, as well as all those who love nature.

INTRODUCTION

Most people only think of mushrooms in relation to food, with questions such as: is it edible or poisonous? Will that be tasty with garlic butter? How do you cook those? Indeed, when I tell people that I’m going to paint a mushroom, they look at me strangely and say, ‘You mean you’re not going to eat it?’

But fungi carry so much more significance than this, even within culinary terms, being crucial for baking breads, brewing beer and wine, the blue in your blue cheese and Marmite (love it or hate it), among many other things. Mushrooms are often termed as being ‘meaty’ and indeed have been a meat alternative for many years; this is especially important in current times, as eating less meat is considered more eco-friendly. We have products including Quorn and tempeh, and edible wild mushrooms such as the so-called ‘chicken of the woods’ or the apricot-hued chanterelles.

A colourful collage showing the fantastic range of fungal diversity, an array of hues, textures and forms, all with the potential to become painting subjects.

Garlic Mushrooms, a painting I did when I was a chef many years ago. I have cooked a lot of these over the years, with lashings of cream and lots of parsley sprinkled over the top!

THE IMPORTANCE OF FUNGI

Fungi are important as decomposers and natural recyclers and without them the planet would be drowning in dead trees, leaves, plant detritus and matter that would not be able to rot down. Considering how important these organisms are to the fundamental processes of our planet, they are often still much maligned and misunderstood. In the UK, the name toadstool is usually given to poisonous mushrooms and in the past, they were once seen as evil or magical as they mysteriously appeared overnight from mud and dung. This fear of fungi or mycophobia was commonplace in Western countries, but not so much in southern Europe and further east, where fungi were relished. They have always been a favourite food of the Greeks and Romans, with delicacies such as the Caesar’s mushroom – Amanita caesarea – most definitely on the menu. In China and Japan, shitake mushrooms have been in cultivation for many centuries.

The name ‘toadstool’ may have come from the German word ‘tode’ meaning death and in some tales, toads were sometimes pictured sitting on mushrooms catching flies with their tongues. Interestingly, toads do secrete poisonous alkaloids from their skin that are similar to some mycotoxins. It is also said that the Celts regarded eating fungi as a religious taboo and only members of the priesthood could consume them. The Welsh name of caws llyffant, literally meaning ‘toad’s cheese’ gives a similar regard to fungi as the rest of the country.

In many cultures around the globe, certain mushrooms were used in religious ceremonies in order to speak with the ancestors, connect with the gods or for spiritual enlightenment. The mushroom stones of the Maya are relics from this time. It is also believed that some mushrooms were used to enhance performance, with examples of Viking warriors to athletes in the ancient Olympics.

The ancient Egyptians thought of mushrooms as ‘the plants of immortality’ and they were also described as ‘the food of the gods’ in the Egyptian Book of the Dead; they were sacred, and only the pharaohs and members of royalty were allowed to consume them. Many species are seen depicted in hieroglyphs that are 4,500 years old.

Of course, there is a darker side to fungi; a few are deadly poisonous, and some are parasitic on plants, animals and even other fungi. Others can cause serious problems for agriculture and forestry. A water mould called Phytophthora ramorum has caused extensive damage to forests, infecting many tree species, and large swathes of larch have had to be felled to keep it in control. Recently, ash dieback has also caused havoc with our native woodlands here in the UK, and also honey fungus with its pernicious black bootlaces.

‘Poisonous mushrooms as Dioscorides saith, groweth where old rusty iron lieth, or rotten clouts or neere to serpents dens, or roots of trees that bring forth venomous fruit.’ Quote from The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard, which was first published in 1597. With quotes such as these, one can see how the British at this time feared all things fungal. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

On the flip side, they can also protect plants from being eaten by pests by allowing them to create chemical defences to counter any attacks. So, although there are some fungal parasites that damage their hosts, the majority of fungi are saprophytic, acting as nutrient recyclers of dead plant and animal matter, and even tough material such as lignin in dead wood.

Fungi are hugely important to us as many medicines are derived from them, including penicillin (and other antibiotics), cyclosporin, an immunosuppressant drug used in organ transplants, many anticancer drugs, cholesterol lowering statins, and psilocybin, the psychedelic substance recently found to help with depression. But as well as curing, fungi are capable of causing serious diseases in us too.

Fungi are present underfoot in soils all year round, and not just in autumn with their strange and ephemeral fruiting bodies. The cells of most fungi grow underground as thread-like structures called ‘hyphae’ and they form networks of mycelium. These fungal root-like filaments connect and envelop the roots of trees and plants to form symbiotic relationships. In fact, over 90 per cent of all plant species have mycorrhizal relationships with fungi and would struggle to survive without them. The fungi can help the plants grow by increasing the uptake of water and essential compounds, such as nitrate and phosphate, and the fungi receive sugars in return. These vast networks that spread beneath our woodlands have become known as the ‘wood wide web’ and they connect trees to one another, allowing them to transmit signals and balance out nutrients between them, effectively communicating underneath the ground; they even look like a neural network. Some plants that contain no chlorophyll such as bird’s-nest orchids (Neottia nidus-avis) gain their nutrients via this mycelial network.

There is now evidence that these associations were essential in the first land plants millions of years ago; the actual age of the Fungi Kingdom is estimated to be over a billion years old, when life on Earth was still confined to the oceans. Fossilised fungi called Prototaxites have been found that date back to around 450 million years ago. These fungi were the largest organisms around at that time and may have resembled tree trunks.

These interactions between fungi and forest are unseen above ground and we do not see how interconnected everything is; a quiet and secret mycorrhizal world runs beneath our feet.

Many insects also have symbiotic relationships with fungi, including leafcutter ants and some termites, primarily farming the fungi as a food source. Fungi can help the insect kingdom too. As a defence against predators the Marbled White butterfly contains toxins. These are derived from its caterpillars targeting grasses that have fungi within them that produce alkaloids. Great news for our honeybees too, fungi species have been discovered that can attack and kill the Varroa mite that is responsible for devastating bee populations around the world.

‘If you go off into a far, far forest and get very quiet, you’ll come to understand that you’re connected with everything.’

ALAN WATTS

THE CLASSIFICATION OF FUNGI

Fungi were once thought of as lower plants and so classified within Plantae, the Plant Kingdom, but in 1969, were at last given their own kingdom. They are very distinct from plants in that they do not photosynthesise, and they have cell walls made from the protein ‘chitin’ and not cellulose. Fungi are genetically more closely related to animals than to plants; insects and crustaceans have exoskeletons also composed of chitin.

Here the Kingdom Fungi is split into five branches making up the True Fungi: with the Basidiomycota being the most advanced and Chytridiomycota being the most primitive and possibly the ancestors of all fungi.

They cannot ingest their food but instead their hyphae secrete digestive enzymes that break down their substrates to simpler components that they can then absorb as nutrients. You could think of them as inside-out organisms.

Kingdom Fungi is incredibly large and diverse including microorganisms such as moulds, rusts and yeasts, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. There are roughly 100,000 species worldwide but there could be many, many more still unrecorded.

The study of fungi is known as mycology, and the word comes from the ancient Greek mykes, meaning mushroom. The word mushroom may have come from the old French term mousseron meaning moss, possibly suggesting its preference for damp, mossy habitats, or a likeness to lower plants.

NAMING OF SPECIES

The British Mycological Society is now over 100 years old and has done much to bring Kingdom Fungi to the attention of the general public. They recently published a list of English common names for fungi on their website, to hopefully engage people with this somewhat unknown world more on a personal...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.2.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Schlagworte | animals • ART • artists • Botanical • Butterfly • Case study • charcoal • Composition • conservation • drawing • Field study • Forest • Fungi • Gouache • Graphite • illustrate • Illustration • INK • Insects • Invertebrates • learn • learning • lichens • mark making • media • mushroom • Mycology • Natural History • Nature • ornithologist • painting • palaeontologist • PEN • pen and ink • Sciart • sketching • Specimens • Step by Step • subjects • toadstool • Watercolour • wildlife |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4333-2 / 0719843332 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4333-4 / 9780719843334 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 71,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich