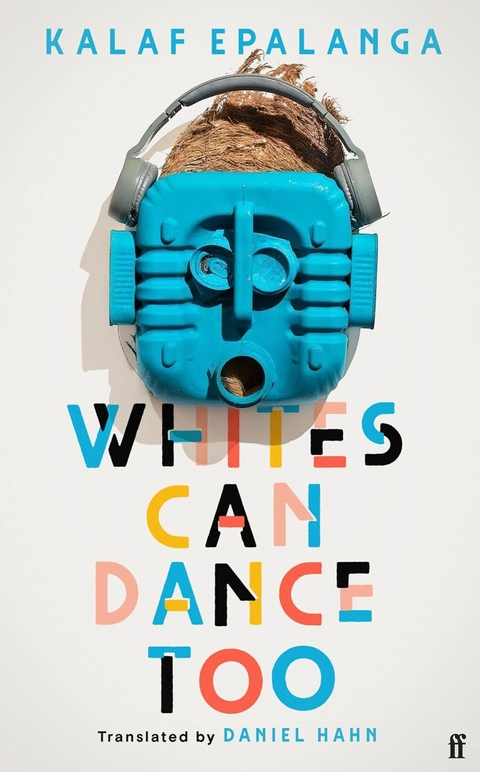

Whites Can Dance Too (eBook)

256 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-37145-7 (ISBN)

Kalaf Epalanga is an Angolan musician and writer. Best known internationally for fronting the Lisbon-based dance collective Buraka Som Sistema, he is a celebrated columnist in Angola and Portugal. Whites Can Dance Too is his acclaimed debut novel; it was first published in Portugal by Editorial Caminho (2017). Epalanga is currently based in Berlin.

An exhilarating debut novel told through three different voices, Whites Can Dance Too is Kalaf Epalanga's reflection on and celebration of the music of his homeland, the intertwining of cultural roots, and freedom and love. It took being caught at a border without proper documents for me to realise I'd always been a prisoner of sorts. Kuduro had been my passport to the world, thanks to it I'd travelled to places I'd never dreamed of visiting. But the chickens had come home to roost . . . Hours before performing at one of Europe's most iconic music festivals, Kalaf Epalanga is detained at the border on suspicion of being an illegal immigrant. Trapped, his thoughts soon thrum to the beat of kuduro, the blistering, techno-infused Angolan music which has taken him from Luanda to Kristiansund, Beirut to Rio de Janeiro, Paris to Lisbon. Shifting between his reflections while incarcerated, and the stories of Sofia - Kalaf's friend at the heart of the Lisbon dance scene - and the 'Viking', the immigration official holding Kalaf's fate in his hands, Whites Can Dance Too is a celebration of the music of Epalanga's homeland, and a hypnotic paean to cultural roots, to freedom and love. 'Both a manifesto and a love story . . . Electrifying . . . What you will find is a story so compelling and visceral that it has the power to move your heart and remind you that the only real borders are the ones we set around ourselves.'Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King (shortlisted for the Booker Prize)'A hugely original, lyrical odyssey through space and identity. Epalanga is one of the most essential voices from that liminal space between Africa and Europe, and though this novel's flavours are specific, its themes are universal.'Johny Pitts, author of Afropean: Notes from Black Europe

1

Quito Ribeiro, the movie editor who put his arms round my waist in my parents’ living room, asked: ‘Who invented kizomba?’ OK, so the question wasn’t actually directed to me. Still, since somebody else had dodged answering it and what with me being the only dance teacher at our weekly gathering of family and friends, they pushed the poor lad into my arms so I could tell him and, also – oh just ‘by the way’ – show him how to dance it. Poor thing. I looked over his shoulder to see Mário Patrocínio, who’d brought him over, standing by the window alongside my neighbours, Samira, Gilson and Vemba, giggling at his awkwardness. But something else caught my attention. Outside, the neighbourhood was still bright – no sign of autumn approaching. A sultry sun descending behind the Serra de Sintra tinted the clouds with shimmered orange, casting saffron and gold reflections onto building facades, trees and the cable stone in the pavement. On the opposite wall of our living room, a Mondrian persimmon square rests over the Serra da Leba picture my folks hung on the wall when we moved in. I was four years old and I don’t have memories of that moment, but I always felt the picture was like a second window, especially at the end of the afternoon. Once they entered our apartment, all our Angolan friends immediately said we were at the border between Sintra and Huíla, which filled my parents with pride. The light touched my dance partner’s clove-and-cinnamon skin and made him glow as if the sun desired him more than anyone else in the room. He had a long, handsome face, a scruffy beard hiding his chin. Whenever his hooded brown eyes caught mine, I had to look away.

So how did I get to know kizomba myself? While all my friends were being told old folktales for their bedtime stories, Paizinho, my stepfather, preferred to talk to me about his musical heroes, from Bonga to Belita Palma, Cesária Évora to Eduardo Paim. He’d start with that gruff, solemn voice of an old-school radio announcer, waving his hands with a childish excitement that contrasted with the white hair of his perennially well-trimmed beard.

‘Eduardo Paim disembarked in Lisbon at the end of the 1980s, bringing old semba songs with him, the embryo that came into contact with the African diaspora and made kizomba.’

He always liked illustrating those musical stories with dance steps too. So I guess it was inevitable I’d end up with a taste for African music. I’d heard of Eduardo Paim before I heard of Rapunzel. I don’t know much about Snow White, but I could tell you that before Eduardo Paim, nobody had ever dared mix Angolan semba with zouk. What 1993 meant for kizomba is always right there on the tip of my tongue. Tropical Band released Só Pensa Naquilo, Ruca Van-Dunem dropped SK … Ainda, Moniz de Almeida gave us the great Tio Zé and Tabanka Djaz released two back-to-back classics, Tabanka and Indimigo. But of all the albums released that year, Paulo Flores’s Brincadeira Tem Hora is my favourite. That album has bangers like ‘Cabelos da Moda’ and ‘Amores de Hoje’, and a heartfelt paean to the kizomba’s co-inventors with the song ‘Tributo a Cabo Verde’. If there hadn’t been this complicity between the two communities, partners in poetry and in revelry, who could have taught Paulo Flores to sing in Creole?

‘Follow me, don’t be scared. If you trip, just stop, and we’ll start over. It’s all gonna be fine,’ I whispered into Quito Ribeiro’s ear, and his hands started shaking. Adorable. I think it’s pretty charming when men can show they’re afraid. ‘First step,’ I murmured. ‘The gentleman always starts by moving left, OK? We’re gonna do the basic step, the foundational one, from two- to eight-four time’ – and off we went onto the floor, harmoniously synchronised, moving left to right and back again, 1-2 step, 3-4 step, 5-6 step, 7 and 8 and … again.

My thoughts were instantly filled with the steps I taught my students in the beginners’ group on alternate days, but I tried to push that image away and focus on the question that brought us together. ‘Who invented kizomba?’ Actually the guy wasn’t coming out of this too badly. I told him that the secret of kizomba is that it’s an earth dance. No need to pick up your feet all that much. ‘Feel the floor,’ I said again whenever I caught one of his feet outside the intended pattern. This thin, metre-eighty guy had fallen into my arms so suddenly I hadn’t even had the time to ask myself how he picked up the swing of kizomba so fast, but being Brazilian explained a lot. Their experience with couples’ dances like forró and lambada gives them an advantage over other groups. Not even the Argentinians with their tango get it. Apart from them, maybe only the Cubans with their merengue and salsa. Quito Ribeiro’s only really glaring mistake was his tendency to raise his hip just a touch at every turn.

It felt good going back to my dance-teacher mode. I missed my dance classes. For the last couple of weeks, working on my final thesis forced me to stay home and, even though we did have our Sunday gatherings, people came for the food, not to get dance classes from me. But here I was, saying to Quito Ribeiro that, unlike bachata, we didn’t raise our hip in kizomba. He smiled and immediately corrected himself. I wanted to congratulate him for being such a fast learner, but I held my tongue and rested my head on his shoulder – longing for my dance classes, to go out clubbing and dance with a stranger.

My neighbours Gilson and Samira joined us on the dance floor. By the time their bodies had met, the music had switched to a song in Cabo Verdean Creole, and suddenly the rest of the crowd who had gathered by the window were no longer interested in us dancing; the debate had moved to which nation should claim kizomba. The Angolans presented their arguments first, saying that since the name of the genre in Kimbundu means ‘party’, there’s no way it could have been invented by any other group than themselves. But the Cape Verdeans in the room threw their arms in the air – the name might be Angolan, but, they grumbled, that doesn’t diminish Cabo Verde’s contributions. Born in Mindelo and raised in Rio de Mouro, Samira weighed in from the dance floor.

‘This music is influenced by zouk from the French Antilles, which also means “party”, right?’

The crowd nodded in agreement, and when she had finished the vírgula and transitioned to the basic two-step, she continued:

‘Maybe the artists who created it decided that kizomba was the best word because of its meaning.’

Paizinho told me that when he arrived in the city, Angolans and Cape Verdeans wandered around Lisbon together, from club to club. From the Aiué to the Kandando, the Kussunguila to the Quo Vadis. The choices were abundant. They had Ondeando, B.Leza, Enclave and Lontra, the first African disco to be labelled mainstream. To show me how awesome Lisbon was back when they were party animals, my parents loved bragging that in August 1993, Prince picked Lontra for a private after-party, following his show at the Alvalade Stadium.

I repositioned Quito Ribeiro’s hand, moving it onto my lumbar region. Sweat on my back. My thighs gently touched his, not imposing myself but suggesting how he should proceed. Usually, first-timers would stop before the end of the song; not Quito Ribeiro. He didn’t seem to care about the change of roles. It looked like he was leading almost imperceptibly to anybody watching us, but he was actually copying what my thighs told him to do.

Truth was, he didn’t dance badly at all. He moved ceremoniously, on the beat, but without neglecting the gracefulness and the joy you need to have while dancing. As if he was coming back to someplace familiar and as if it wasn’t his first time dancing kizomba. It didn’t have anything to do with our sharing an ocean or a language. I felt it was something else, and not just the music; perhaps it was the vulnerable way he’d let himself go. I was intrigued.

‘Sorry, did I do something wrong?’ he asked and I looked up.

‘No,’ I said, grinning. ‘You’re doing just fine.’

‘Your eyes are saying the opposite.’

‘I thought our feet were doing the talking,’ I said.

He then stopped and steered my body to the side, his eyes locked in, biting his lower lip so as not to lose focus. Then, when our bodies joined again, our faces were a hand’s breadth apart.

‘How did I do?’ he asked.

And just like that, what had been puzzling me became clear. Quito Ribeiro’s soft and nasal tone, with his stretch of the vowels in diphthongs, made him belong, effortlessly, to the place I called home. And wow, I really didn’t want that song to end. All I desired at that moment was to rest my head on his shoulder and decipher in detail that woody and citrus scent on his neck.

‘So, you won’t tell me?’ he insisted, creating a pair of dimples on his cheeks as he showed me his perfect teeth.

‘You’re a fast learner,’ I said, though...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.6.2023 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Daniel Hahn |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Pop / Rock | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-37145-0 / 0571371450 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-37145-7 / 9780571371457 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 374 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich