Collectors, Commissioners, Curators (eBook)

284 Seiten

De Gruyter (Verlag)

978-1-5015-1485-2 (ISBN)

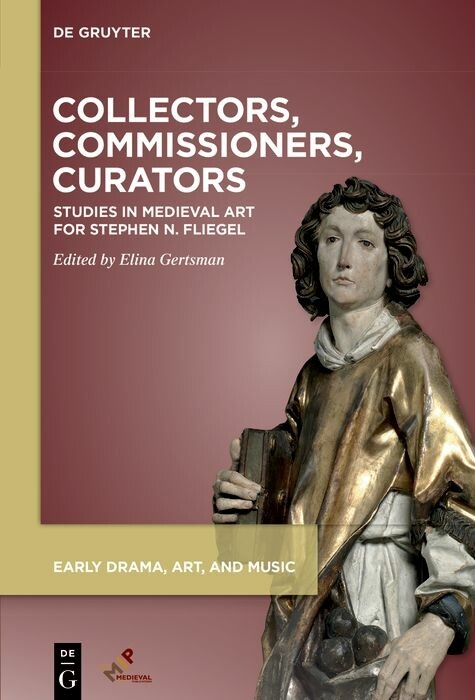

This volume celebrates the storied career of Stephen N. Fliegel, the former Robert Bergman Curator of Medieval Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA). Authors of these essays, all leading curators in their fields, offer insights into curatorial practices by highlighting key objects in some of the most important medieval collections in North America and Europe: Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Louvre, the British Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, the Getty, the Groeningemuseum, The Morgan Library, Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum, and, of course, the CMA, offering perspectives on the histories of collecting and display, artistic identity, and patronage, with special foci on Burgundian art, acquisition histories, and objects in the CMA.

Elina Gertsman, Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, USA

This volume celebrates the storied career of Stephen N. Fliegel, the former Robert Bergman Curator of Medieval Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA). Authors of these essays, all leading curators in their fields, offer insights into curatorial practices by highlighting key objects in some of the most important medieval collections in North America and Europe: Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Louvre, the British Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, the Getty, the Groeningemuseum, The Morgan Library, Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum, and, of course, the CMA, offering perspectives on the histories of collecting and display, artistic identity, and patronage, with special foci on Burgundian art, acquisition histories, and objects in the CMA.

Preface

Some years ago, I had the good fortune of co-curating a centennial focus show at the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA). The driving force of the exhibition—its real architect—was Stephen N. Fliegel, then the museum’s Robert P. Bergman Curator of Medieval Art. The show coalesced around the famous Gothic fountain, the only extant object of its kind, complex and breathtakingly gorgeous (Figure 0.1). Even amid some truly spectacular loans (Jan van Eyck’s Madonna at the Fountain and the Grandes chroniques de France, to name just a couple), it shone, figuratively but also literally, light bouncing off its intricate polished surfaces, its enamels as gleaming and changeable as sea water, its small bells stilled but pregnant with the expectation of movement.

The fountain seems to embody some of the key things that Stephen loved about being a curator. One, it came to us with an excellent, if improbable, mystery story: found, allegedly, in a ball of earth in an Istanbul palace garden. Two, although the fountain was likely created in Paris sometime between 1320 and 1340, it gestures both to the lavish entremets treasured in a Burgundian milieu and to monumental fountains like Claus Sluter’s Well of Moses, another Burgundian tour de force; Stephen’s love of Burgundian splendor was patently on display in his breathtaking show “Dukes and Angels: Art from the Court of Burgundy, 1364–1419.” Three, it is a Cleveland object par excellence: spectacular, refined, rare, and undergirded by an unlikely curatorial triumph—refused by the Louvre when still partially encased in dirt, it was subsequently snagged by William Milliken (who helmed the department of decorative arts at the time) to become a centerpiece of the museum’s medieval collection. Four, its shield-shaped escutcheons emblazoned with eight-pointed stars raise all manner of thorny, and therefore challenging and exciting, questions about attribution, patronage, and dating.

The present collection loosely follows these four paths of inquiry. The first part of the book features essays that explore complicated itineraries of objects, querying issues of reconstruction, reunification, and reappraisal. All three, in a way, unfold as investigative stories. In a brief vignette, “St. Stephen in Stone,” which opens the book with an appropriate nod to Stephen’s namesake, Paul Williamson seeks to reunite the body of a sculpted St. Stephen with its long-lost head, knocked off during the French Revolution and only recently rediscovered. At the end of his essay, Williamson offers a succinct reflection on the curatorial choice of displaying severed heads and decapitated bodies in museum settings, suggesting that they acquire new lives as objects of a peculiarly modern kind of contemplation. In the essay that follows, Lloyd de Beer reunites not heads and bodies but alabaster panels from a long-disassembled altarpiece. Building his case from the ground up and paying particular attention to the panels’ style, carving technique, size, and current condition, de Beer concludes his painstaking inquiry with a spectacular reconstruction of the original altarpiece, emphasizing the enormous value of considering a vast corpus of objects, long seen as disparate and fragmentary, holistically. Such holistic analysis also frames Roger Wieck’s bracing narrative that traces the peregrinations of an elusive fifteenth-century folio featuring the Parliament of Heaven. In service of understanding where the leaf really belongs, Wieck parses its iconography, contextualizing the folio within its cultural, visual, and theological milieus. If St. Stephen’s head remains detached from its body, and the alabaster altarpiece remains split in (at least) five disparate pieces, Wieck’s folio—which, at some point, comes close to rejoining its original Book of Hours only to escape curatorial grasp—by a stroke of good fortune and dint of unlikely circumstance, finally regains its home.

The vicissitudes of fortune similarly undergird the subject of Sophie Jugie’s essay, which opens the second part of the book dedicated specifically to the arts of Burgundy. Jugie focuses on a stunning sculpture of the Virgin and Child, now attributed to one of the luminaries of Burgundian art, Claus de Werve. Repainted several times, then whitewashed, and subsequently stripped of polychrome altogether, the sculpture was misdated and ignored by generations of art historians; Jugie, through a deft historiographic tour de force, returns the object to its rightful place in the Burgundian corpus, demonstrating how deeply ingrained scholarly views can interfere with our ability to really see a work of art. In the following essay, Elizabeth Morrison, by exploring the library of Anthony of Burgundy, likewise upends prevailing academic opinions—this time by memorably suggesting that Anthony’s books should not be “treated as clinical data points to be gathered in a post-mortem inventory.” Instead, Morrison proposes to explore these manuscripts chronologically, as the building blocks of Anthony’s biography that reflected his changing interests, concerns, anxieties, and ambitions. This kind of approach, characterized by a careful tracing of historical vagaries and dynastic connections, also informs the essay by Stefan Krause, which brings us into the sixteenth century when the Hapsburgs received the so-called “Burgundian inheritance.” Krause analyzes the ceremonial armor for Archduke Charles that stands at the nexus of intrigue, political haggling, and social ceremony, in which Burgundy played a major role—a testament to a failed alliance and a triumph of armorer’s art.

Chivalric art of the highest caliber is on full display in the Völs-Colonna ensemble, the woefully understudied centerpiece of the CMA’s collection of arms and armor, and the focus of Donald La Rocca’s essay that opens the third part of the book, a section dedicated specifically to Cleveland objects. La Rocca traces the armor’s provenance and composition, while paying particular attention to centuries-old collecting practices, and signaling this ensemble’s place in the intertwinement of the curatorial decisions of the CMA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA). The relationship between these two great American institutions as reflected in the history of their objects is similarly the topic of Griffith Mann’s essay that explores the historical ties that bind two sculptures, St. John the Baptist at the CMA and St. Catherine at the MMA, both attributed to the Netherlandish sculptor Jan Crocq. Mann focuses not only on the medieval but also on the modern history of the two sculptures, which, over the years, have fallen in and out of favor in tandem with changes in art historical methodologies and fluctuating art market trends. Crocq’s St. John the Baptist stands as a key witness to Stephen’s curatorial acumen, amply demonstrated in scores of object purchases the CMA completed under his guidance; few are more striking than the marvelous Mosan Madonna, explored in Gerhard Lutz’s contribution. Paying particular attention to the sculpture’s polychromy and use of colorful cabochons (now lost), Lutz contextualizes the Madonna and Child within the sculptural production around the year 1300, drawing parallels with contemporaneous objects all across Europe and reaching up to Scandinavia. This sculpture is particularly dear to me: it was one of the first objects to which Stephen offered me a sneak peek, before it was officially announced to the public, and I clearly remember Stephen’s infectious enthusiasm with which he introduced the sculpture to my students just as soon as it was installed in the gallery.

Whatever delight Stephen experienced with the Mosan Madonna, it paled in comparison to what he considered then, and considers still, to be his most beloved acquisition, the icon of the Virgin Eleousa attributed to Angelos Akotantos (Figure 0.2). When I asked him to reflect on it, Stephen admitted that he “was emotionally vested in the icon like none of the others.” Until the object came to the CMA in 2010, the collection had no painted icons—a tremendous gap in its holdings, and one that Bob Bergman, then the museum’s director, charged Stephen with filling as far back as 1993. Stephen said that he “came close on several occasions, but something was always missing—condition, quality, an appropriate subject, provenance.” When he learned about the Akotantos icon that was for sale by a private collector, it took him months of difficult negotiation as well as several trips to Rome to strike the deal. “I was exhausted at the end,” Stephen said, “but I felt the perfect icon for Cleveland had been found.” After a complicated conservation process, the icon was put on display in 2012, quite appropriately, in the Robert P. Bergman Memorial Gallery of Byzantine Art, where it now accompanies another icon, the New Testament Trinity, that Stephen helped acquire just a few years later.

The two icons serve as the starting point of Maria Vassilaki’s essay, which opens the final section of the book where three scholars reflect on one of the oldest curatorial conundrums: the thorny issue of attribution. In her article, Vassilaki brings up an astonishing case of a group of Sinai icons, including one by Akotantos, that were overpainted as well as supplied with arbitrary dates and signatures by a Cretan artist who came to stay at the monastery sometime at the end of the eighteenth century. Vassilaki cautions...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5015-1485-7 / 1501514857 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5015-1485-2 / 9781501514852 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 22,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich