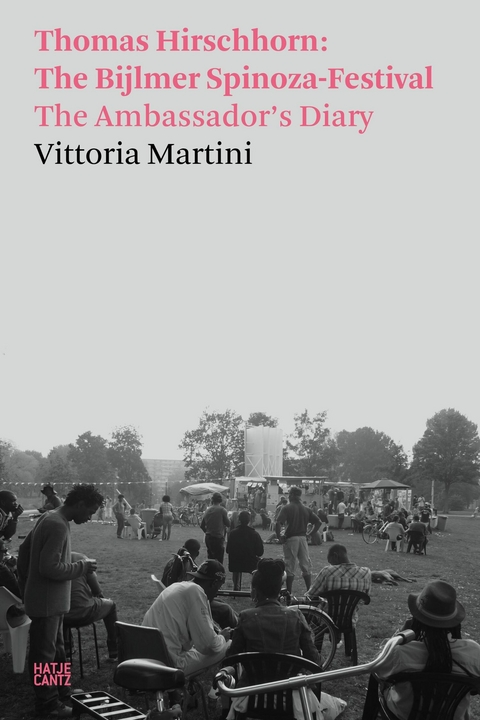

Vittoria Martini (eBook)

188 Seiten

Hatje Cantz Verlag

978-3-7757-5264-0 (ISBN)

Note to the Reader

Introduction

Marcus Steinweg, Spinoza Theater, 2009

The Bijlmer, Amsterdam, May 19, 2009

Letter to Lisa Lee, First Exchange on The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival, May 26, 2009

“The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival will not be ‘just another project’ amongst others. Because of its complexity, its irreducibility, its location, its exaggeration, its becoming possible and the extreme situation of solitude. The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival is a hyper-complex and extra-ordinary incomparable project.”1

T. Hirschhorn

“I have tried not to lose hold of the first movement of things as it appears in the notebooks, the tripping from day to day.... I could hardly believe that each morning there were new things to see in the pictures, new things to think about, words for them ready to hand.”2

T. J. Clark

If I find myself writing the introduction of this book ten years after the dismantling of The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival, it is because this work has never ceased speaking to me all this time. It’s kind of like when you are in the midst of research and the object of your study seems to fit with every stimulus you receive, with everything you see or hear, even when it doesn’t seem to logically, automatically, or directly fit.

During this time, I experienced a first phase of physical recovery, which was followed by a longer period of psychological recovery: living for two months, every single day, for ten hours a day, deeply immersed into The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival, sleeping a step stone away from it, with its presence carved even into my evenings. It was an experience that would push anyone to their limit. The last week there I clearly felt the first physiological symptoms due to a heterotopic feeling—as precisely described by Michel Foucault. This condition was amplified by the excessive production and the repetitive automatism of pursuing the same actions, the same routine, every single day. There was the constant pression of time, a time that, although defined tightly by the daily program, had led me to live in a state of exception, of alienation, of extreme solitude. A prolonged exposure in an elsewhere without a specific place, although very defined, where it had become impossible to locate myself, not knowing where I ended and where the others began. A suspended but concentrated time where every gesture and every relationship became significant. Living in the “here and now” is like being constantly present to yourself, in the instant of the lived moment that does not contain a memory of the past, but only an awareness of that precise moment, with its amplified and memorable being endlessly forming intricate layers of memory.

Distance was needed, a gaze from afar, in order to be able to distill and analyze the experience. Distance was needed from the “here and now.” Distance was needed in space, and distance was needed in time.

This time has passed, and the work has started to resonate. It has become what Thomas Hirschhorn wrote in his initial statement, well before it came to life in its material form: a sculpture that can be transplanted “first of all in the mind.”3 The lapse in time has allowed the disappearance of aphasia and The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival has exploded in my head, with all its strength and beauty—a beauty as tough as the reality of a life lived consciously in the here and now, like an incredibly vivid memory that has reemerged of the presence of my body in that space.

Gilles Deleuze explains it with a great deal of clarity: through Spinoza, the human being can come to understand that the happiness of each of us is triggered by what happens accidentally in our lives, but only if we learn to distinguish what it is good for us (and makes us better) from what hurts us (and makes us weaker); then, we could all reach a state of bliss and joy in this life. The effort of living lies exactly in this constant choice.

It is precisely the conatus that resounded every day as the only understandable word to me from the Dutch text of the Spinoza Theater. It was staged every evening: “CONATUS, which holds everything together. / In the here and now of the only world.”5 Conatus: the power of being true to one’s nature and, in the case of human beings, to one’s own body. Conatus as effort, attempt, impulse that can also lead to failure, but which allows you to continue being yourself, to nourish what Spinoza defines as Appetitus, which in the human being is driven by the will and becomes Desire.6 The human being is then seen as a body that constantly desires to strengthen itself by trying to avoid Tristitia for Laetitia. “The ethical task is to do everything you can,”7 as Deleuze notes in his explanation of how the body is at the center of everything for Spinoza, because it is with the body that the human being “extends his strength as far as possible.”8 Basically, the more I am and the more I desire, the happier I could become. Joy and desire are the engines of being; they are the vital power of the body itself and everything lies in the awareness that you conceive of yourself.

In retrospect, it becomes crystal clear why Thomas Hirschhorn chose Spinoza for such a sculpture/festival:9 because he is the philosopher who most of all recognizes joy in the awareness of living itself and as the engine of vital energy. That is why, I guess, he kept repeating (often laughing: we laughed a lot there), that the word “nostalgia” should not even have been said at The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival.

It becomes clear why, among all the propositions of Spinoza’s Ethics, he underlined with a pink highlighter the thirteenth proposition of the third book: “Love is Joy accompanied by the idea of an external cause.”10 As a matter of fact, The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival is an artwork about “coexistence” and that is the definition of “love” for Spinoza.

It becomes evident why this complex evolving sculpture carries in its title, together with Spinoza, the word “festival,” immediately declaring its nature as an event and, as such, with a limited duration in time and space. The sculpture is desperately here and now, there is no possibility to experience it elsewhere, there will be no possibility to experience it in the future.

And yet it becomes fully understandable why, in a conversation about The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival with Jacques Rancière in 2010, Hirschhorn defined the “Presence and Production” as a “challenge, a warlike affirmation . . . a gift, an offensive and even aggressive gift.”11 As a matter of fact, according to Spinoza, this dynamic that leads to happiness must be perpetual, active, consciously played in every moment that makes up days, and this is at the center of Hirschhorn’s “Presence and Production”—and this is exhausting not only for him, but for anyone who agrees to be involved in his work. But the effort highlights the preciousness of time, of the moments of beauty and grace visible only to those who are ready to see them even in the banality of the place where they find themselves living their daily lives, and it is only by producing that their presence in the world acquires meaning. This dynamic of empowerment of our presence in the world, and of the expansion of our being as far as possible, automatically leads to a self that is inclusive, a self that welcomes others in itself as active elements of production of desire and therefore of power, vitality.

Now, all this theoretical Spinozian discourse, turn it upside down in a precise “here” that is a sculpture, an artwork, a finished form that exists as such, and in a precise “now” that is May and June 2009. This work no longer exists on a specific date, not only in that space and that time, but in absolute terms: its materiality no longer exists. It is not a lost or destroyed artwork, but one that was conceived with an obsolescent formality and that makes sense for the history of art precisely because it contains the formal temporality inscribed in its own being: without that precarious element, The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival would no longer exist. The thought eludes . . . It seems an oxymoron, but the power of the work is given by its existence in a time and place that have been so precise and yet have become universal. Since the moment it formally ceased to exist, its life as a work of art in its entirety began.

The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival has become an archetype and a metaphor because it is a machine that allows the experience of art itself and does it through the productive philosophy of Spinozian existence. The Spinozian productive philosophy, applied in the here and now that is a work of art, has defined its existence as such.

It became so clear that my physical and mental exhaustion following the experience was the precise and concrete result of Spinoza’s philosophy of life as well as Thomas Hirschhorn’s artistic production methodology (“Energy yes! Quality no!” which he repeats like a mantra). Do everything you can, exaggerate, overproduce—like soldiers in the trenches, you must fight every moment against resignation, nostalgia, all “affections” that bring weakness because it is art that requires it, because it is life itself that requires it in one of the most vital and joyful affirmations that can be encountered. And being next to Thomas Hirschhorn is exhausting, dreadful: it requires constant effort, it is a continuous challenge to your own certainties without refuge to shelter, without space for thought to rest. At the same...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Hatje Cantz Text | Hatje Cantz Text |

| Mitarbeit |

Designer: Neil Holt |

| Verlagsort | Berlin |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Schlagworte | Großstadt • Kunst im öffentlichen Raum • Kunsttheorie • Niederlande • Philosophie • Skulptur • Zeitgenössische Kunst |

| ISBN-10 | 3-7757-5264-1 / 3775752641 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-7757-5264-0 / 9783775752640 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 15,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich