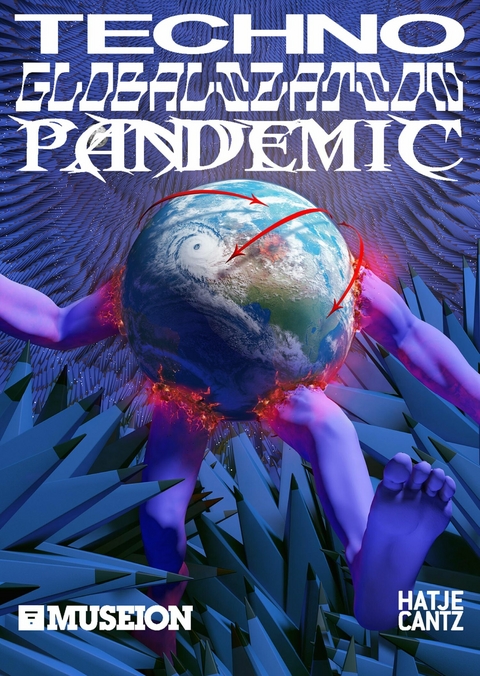

Techno Globalization Pandemic (eBook)

212 Seiten

Hatje Cantz Verlag

978-3-7757-5430-9 (ISBN)

Cover

Title

Copyright

Table of contents

Part-Time Techno

Caught in the Strobe

Critique of the Plague Rave

techno and liberation

The Techno-Stack

Part-Time Techno

Im Bann des Strobo

Eine Kritik des Plague Rave

techno und befreiung

Der Techno-Komplex

Part-Time Techno

Intrappolati nella luce stroboscopica

Per un'analisi critica dei Plague Raves

techno e liberazione

Il conglomerato techno

Matthew Collin

Global Techno Culture in a Time of Tribulation

It’s New Year’s Eve and we’re up on the balcony of Ellen Allien’s apartment in Berlin, and we’re all deep into the party, swirling our way through this glittering cascade of sound, celebrating the moment together. Ellen’s on the decks and she’s got that fierce groove on, jacking to the beat with a zesty young companion bouncing along by her side in a fluffy disco jacket and a red pvc shirt, and we’re gazing out over the balcony and up at the Fernsehturm, the landmark broadcasting tower lit up like an electric filament against the darkness of the Berlin sky as we dance our way into 2021 together…

Except we weren’t at Ellen’s place that night, or any other night. And there was no party—although we saw it all, as clearly as if we had been there.

What we were watching was a virtual dj set, broadcast online; one of thousands of livestreamed simulations of nightlife that proliferated after the coronavirus pandemic triggered lockdowns across the world in 2020, shuttering clubs and canceling festivals as governments struggled to hold back the relentless surge of infections.

In the times before the virus, techno stars like Ellen Allien would have been shuttling back and forth across countries and continents several times a month to play at parties. But now the club doors were closed, she was playing on her own balcony—djing at home for “partygoers” who were all in their own homes too. Dance events became intimate, sometimes even individual experiences: micro-raves with partners or a couple of friends gathered at home, or perhaps just solo sessions, rocking back and forth in the glow of the laptop screen, alone.

Electronic dance music culture developed internationally at around the same time as the Internet became a global phenomenon, and it instinctively took advantage of the possibilities of the online world that grew up around it: a digital culture for digital times. This symbiosis enabled borderless networks to coalesce around any kind of sound that one might hope to invent, creating what the journalist Gabriel Szatan described as “an interlinked infrastructure that allowed artists from Shanghai to perform in Kampala and be broadcast to fans in Bogota or Bratislava.” So when the pandemic hit, this interlinked infrastructure provided the basis for new methods of channeling musical self-expression online.

That meant there were dj sets being livestreamed from the most unlikely places: from the vertigo-inducing summit of a towering grain silo at the Danube river docks in Belgrade; from the Centre for Cosmic Constructions, a decommissioned Soviet-era space research institute near Tbilisi; from the viridescent Opalite-tiled gallery of a historic aquarium in Detroit, and from the stately neoclassical interior of the Neues Museum in Berlin. There were exuberant queer parties on Zoom like Club Quarantine and interactive 3D electronic music venues built within the Minecraft video game like Club Matryoshka, as well as an extraordinary Minecraft replica of Berlin’s Griessmuehle club. There was Lost Horizon, a virtual reality recreation of the Glastonbury Festival’s hedonistic Shangri-La zone for avatar ravers, and there were live online improvisation events like the Stay Home Soundsystem series, streamed from a studio in Rotterdam where Dutch producer Speedy J led mind-expanding electronic jam sessions with different techno auteurs each week.

But none of these virtual extravaganzas, however visually impressive they might have appeared, could conceal the fact that the only communal experience was mediated by the online platform. In this digital replication of a collective memory of what nightlife had been, the one thing that was truly tangible was absence. There was no sweat, no smell, no bodily contact, no snatched conversations amid the cacophony, no chance encounters in the toilets or emotional reckonings at the bar. There was no “us” because we weren’t really there. And without the energies and passions of the dancers on the floor, no party could ever really come alive.

Livestreaming at least served as a kind of collective sonic therapy amid the long nocturnal quietude of the pandemic times, and some of these online events raised money to help out unemployed nightclub workers as they struggled to survive financially during the global shutdown. But livestreams could never really generate enough charitable donations to adequately sustain all of those who made their living in what had become a multi-billion-dollar global cultural industry.

In the year before it was ravaged by the pandemic, the combined worldwide value of the dance music business was estimated at $7.3 billion, according to a report produced by economic analysts for the International Music Summit. From its subcultural roots in the black, Latinx, lgbt and multicultural bohemian club scenes of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, electronic dance music became increasingly globalized from the 1990s onwards. It was initially disseminated across Europe and beyond by true believers who wanted to share the music they adored, but as it became more popular and more lucrative, it also started to attract entertainment companies that had little invested in the culture in terms of personal involvement, musical aesthetics, or ideology; for them, it was just another form of show business. The emergence of international franchises such as the Ultra festivals and dance music business conventions like edmbiz were just some of the signs of how times had changed.

As is customary with global capitalism, the highest earnings went to the few at the top, most of them white males. Business magazine Forbes reported in its annual “Electronic Cash Kings” feature in 2019 that the highest-paid djs that year were The Chainsmokers, an American duo who earned an estimated $46 million in pre-tax income from live shows, recordings and other commercial activities. Like other top earners on the Forbes list, they made a lot of their money from their residency in Las Vegas, the American entertainment resort which had become the glitzy capital of American-style “edm” clubbing.

Like blackjack tables, slot machines and Rat Pack revival revues, electronic dance music was a completely commercial proposition in Las Vegas: hedonism without even the slightest suggestion of countercultural spirit or do-it-yourself philosophy. High-concept Vegas megaclubs like xs and Hakkasan paid their headline djs five-figure sums to play us-style edm: a fast-shifting, fx-overloaded style of dance music that sounded like its black and gay disco and funk heritage had been removed and replaced with the belligerent energy of rock ‘n’ roll: a noise that seemed to have been specifically designed for white American youth. The edmbiz convention brought many of the multinational power players in the dance music business to Las Vegas each year to discuss how to monetize nightlife and its ancillary products, attracting executives from entertainment events giants like Live Nation, Hollywood talent management firms like Creative Artists Agency and music-streaming companies like Spotify, as well as the highest-paid djs on the global circuit. Critics argued that events like edmbiz were symptoms of a sickness that was afflicting dance music culture; a culture which had been created by the marginalized and oppressed but was now being commercially exploited by entertainment corporations. The promoters behind the biggest mainstream dance music festivals insisted that they were simply giving people what they wanted: the highest production values, the most spectacular visuals and the biggest dj stars in the world.

Debates about whether or not dance music has become over-commercialized have been going on almost as long as dance music itself, of course. Even in the much-mythologized early days of Acid house and illegal raves in Britain in the late 1980s, some promoters were already being accused of “selling out” the scene for financial gain: people like Tony Colston-Hayter, who ran the illicit Sunrise parties—some of the most spectacular outlaw events ever organized in Britain. Colston-Hayter, who was once dubbed “Acid’s Mr. Big” by a tabloid newspaper, said he saw raving as “the ultimate hedonistic leisure activity” with no subversive significance; it was “totally non-political,” he insisted. He argued that rave promoters should have been embraced by Britain’s right-wing Conservative government of the time because they were examples of capitalist “enterprise culture.” And yet he also saw himself as some kind of egalitarian standard-bearer who, by staging the biggest raves he could, would allow anyone access to the Acid house experience, not just a “clued-up,” largely white elite. “I didn’t see why it should be kept just to a special few,” he once said.

Dance music culture has long experienced friction between those who see it as a cause, whether artistic or political, and those who argue that it’s not about anything more than the beats and the party. It has also never had any shortage of speculative investors and exploitative “patrons.” By the early 1990s, multinational companies like Pepsi, Sony, and Philip Morris were already trying to buy subcultural credibility by sponsoring clubs and parties, while a millionaire merchant...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Mitarbeit |

Designer: Studio Mut |

| Verlagsort | Berlin |

| Sprache | deutsch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik |

| Schlagworte | Globalisierung • Identität • Techno |

| ISBN-10 | 3-7757-5430-X / 377575430X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-7757-5430-9 / 9783775754309 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich