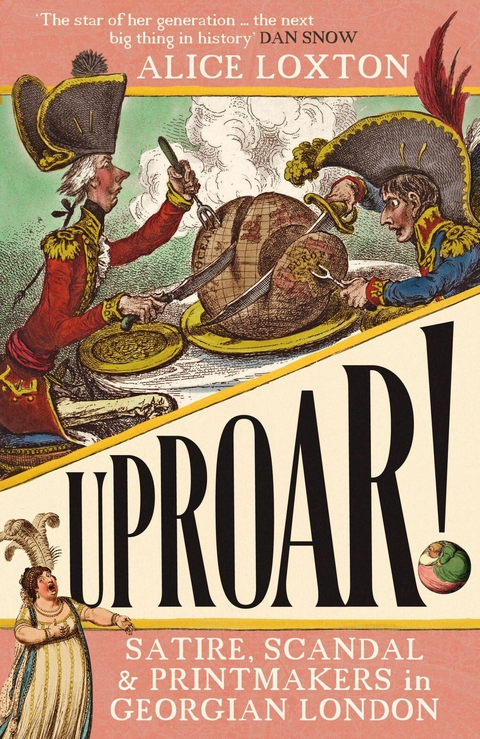

UPROAR! (eBook)

240 Seiten

Icon Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78578-956-4 (ISBN)

Alice Loxton is a history broadcaster and writer. She has over two million followers on social media (@history_alice). She has appeared on many channels including Sky Arts, Channel 5, BBC News and History Hit, and has worked with a wide array of organisations to bring history to mainstream audiences (including Christie's, Meta, The National Trust, 10 Downing Street, The Royal Collection Trust, The National Portrait Gallery and The National Gallery). UPROAR! is Alice's first book.

Alice Loxton is a history broadcaster and writer. She has over two million followers on social media (@history_alice). She has appeared on many channels including Sky Arts, Channel 5, BBC News and History Hit, and has worked with a wide array of organisations to bring history to mainstream audiences (including Christie's, Meta, The National Trust, 10 Downing Street, The Royal Collection Trust, The National Portrait Gallery and The National Gallery). UPROAR! is Alice's first book.

1

A Bench of Artists

A SOBER, DILIGENT PERSON OVER THE AGE OF TWELVE

6 November 1772.1 A fifteen-year-old whippersnapper named Tom scurried through the grimy backstreets of eighteenth-century London. As the bells of St Paul’s tolled out to herald a new day, he tripped and skipped and darted across potholes, broken glass and horse dung. He overheard tavern keepers evict sleeping drunks and caught snippets of gossip from dutiful maids as they carried out their early-morning errands. The November sunlight pierced through dusty windows of ale houses and coffee shops, and the city erupted into life once again.

Stumbling out of this labyrinth, Tom burst out into the wide-open space of one of central London’s most fashionable streets: the Strand, a playground for the super-rich. Tom might have glanced through the shopfronts to gaze upon curious delicacies from across the globe: coffee from Arabia, silks from Madras or furs from New York. He probably passed No. 216, where the tearooms of Thomas Twining emitted the tantalising scent of finely blended tea. Or the bookshop at No. 34, where Samuel Johnson could often be spied, poring over the vast collection of titles. As he trotted westward, Tom was vigilant to dodge the obstacles of the street: the wide, square hoops of fashionable ladies in sack-back gowns, or the hordes of labourers, toiling to complete the latest building schemes of Robert Adam, the great neoclassical architect of the day.

In the early 1770s, Britain was on the brink of transformation. In 1771, the inventor Richard Arkwright opened the first cotton mill at Cromford, Derbyshire, marking the start of Britain’s Factory Age. Meanwhile, up and down the country, thousands of curious punters gathered to listen to the electrifying words of Methodist preacher John Wesley. And across the Atlantic Ocean, long-growing tensions in the American colonies, in which calls for ‘No taxation without representation’ were reaching boiling point, would soon erupt with the Boston Tea Party in 1773. It was on such issues as these that 34-year-old King George III – in the twelfth year of his reign by 1772 – would have consulted his prime minister, Lord North.

Nowhere was the change more apparent than in London, a city which was swelling at incredible pace. It was a thriving metropolis, flooded by thousands of young people each year eager to make something of themselves. In 1700, the city’s population numbered about half a million. By 1800, it would double to 1 million, the first city in Europe to do so since Ancient Rome.2 The streets were buzzing with horse-drawn hackney coaches and trading carts bouncing over the cobblestones, and sedan chairs and pedestrians in their thousands.

All of these were easily avoided by our young friend Tom as he picked his way down the Strand. And today, he was bursting with excitement. For he was heading for the Royal Academy Schools to begin his first day of study. This was the start of his great career to become Britain’s Next Top Artist.

Tom knew these streets like the back of his hand: he was a Londoner born and bred. His family, the Rowlandsons, were of Huguenot extraction. His grandparents still lived in silk-weaving Spitalfields (then green fields to the east). But Thomas’ parents, William and Mary Rowlandson, were based in the beating heart of the City of London, on Old Jewry. It was here that Thomas Rowlandson was born on 13 July 1757.

The family made a respectable living by trading wool and silk. But it wasn’t an easy ride. When young Tom was a toddler, his father’s business hit the rocks. ‘The elder Rowlandson,’ it would be recorded in Tom’s obituary, ‘who was of a speculative turn, lost considerable sums experimenting upon various branches of manufactures, which were tried on too large a scale of his means; hence his affairs became embarrassed.’3 On 16 January 1759, William Rowlandson was declared bankrupt, and to hammer home the humiliation, it was printed in the Gentleman’s Magazine for the world to see.

Creditors seized the family house. William and Mary upped sticks and hurried north to Richmond, Yorkshire. Luckily, William’s brother, James, had made less of a hash of things. He was a prosperous Spitalfields silk weaver, happily married to a generous Frenchwoman named Jane. Having no children of their own, they took in young Tom, allowing him to remain in London.

But tragedy struck in 1764. Uncle James died of fever. Aunt Jane sold the business and moved to rooms on Church Street, Soho. She sent Tom to Dr Barwis’ school on Soho Square, ‘the first academy in London’.4 In language befitting an Ofsted report, the school was said to attain ‘an extraordinary degree of excellence’.5

The school’s founder, Martin Clare, had described himself as ‘M. Clare, School-Master in Soho Square, London. With whom Youth may Board, and be fitted for business.’6 Clare was the author of two utilitarian books: Youth’s Introduction to Trade and Business and Rules and Orders for the Government of the Academy in Soho Square. For just £30 a year, plus a sprinkling of paid-for extras, parents could expect their sons to excel in French, drawing, dancing and fencing, and get a decent grounding in morality, religion and philosophy, too.

When Tom enlisted, in the 1760s, the school was run by Rev. Cuthbert Barwis, who added a dash of theatrics to the mix. Under his thespian leadership, the Soho School became famed for the masterful array of Shakespeare plays performed by the pupils. His eccentricity was not lost on an impressionable cast of schoolboys, who turned out to be an impressive bunch: the actors Joseph Holman, John Liston and Jack Bannister, as well as the artist J.M.W. Turner, all passed through Dr Barwis’ doors.

Tom was popular with his peers, who dubbed him ‘Rowly’.* It was in these boisterous classes where Tom, struggling to engage his mind with competing theories of trade and economics, began doodling. The margins of his books were soon black with scribblings of ‘humorous characters of his master and many of his scholars’.7 In Tom’s fifteenth year, these sketches were considered worthy of more than just textbook marginalia. Probably with the encouragement of Barwis – keen for some more sparkle to add to his list of alumni – Tom was put forward to apply for the brand-spanking-new Royal Academy Schools.

The Academy Schools were part of the Royal Academy of Arts, itself less than four years old after being founded in 1768. It had been launched by the Instrument of Foundation, a scheme signed off by King George III. In a pompous and unimaginative declaration, it claimed to be a ‘well-regulated School or Academy of Design, for the use of students in the Arts, and an Annual Exhibition, open to all artists of distinguished merit’.8

So, this was the official establishment of the hub of British creativity. And the chosen lexicon was … ‘well-regulated’. The British art scene kicked off in a haze of procedure and red tape. How thrilling! How wild! How shockingly subversive! When George III trawled through the 27 clauses relating to membership, government, officers, schools, professors, servants, exhibitions, library, admin, red tape, procedure and admin, his unbridled enthusiasm for this new arm of top brass was duly noted next to a signature: ‘I approve of this plan; let it be put in execution.’9

Despite a muted beginning on paper, the Royal Academy was founded with good intentions. It sought to provide a standard of excellence to a hitherto unregulated and unprofessional art scene. In affiliation with the Royal Academy came the Academy Schools, at which Tom became a student. Originally based in defunct auction rooms in Pall Mall, in 1771 the school moved to extensive space in the old Somerset House in the Strand. This comprised a lecture room, a library, a room for life drawing, known as the Life Room, and a hall filled with casts of classical sculpture called the Plaister Academy.

The entry requirements were tough. Prospective students were expected to be pretty clued up already, having ‘An acquaintance with Anatomy (comprehending a knowledge of the Skeleton, and the Names, Origins, Insertions, and Uses of, at least, the external layers of Muscles)’.10

To separate the wheat from the chaff, candidates were invited to the premises to be tested. Tom had been put through his paces at his interview. He was brought for inspection to the Keeper of the Schools, George Michael Moser, an elderly Swiss-born artist, who had once been a drawing-master to the King, and a specialist in ornamental enamels.*

Moser was happy enough with Master Rowlandson’s submitted samples, but still needed convincing. Tom was sent to the Plaister Academy. For several long, nerve-wracking days, he toiled away on a further set of drawings: marking out every tiny detail, triple-checking his angles and trying to steady his shaking hand. Tom knew that his whole career rested on these studies, and he spent every waking minute working them up to perfection.

The endeavour paid off. His application was approved by the council, and a letter of admission dispatched by Francis Newton, the secretary of the Academy. He was in!

But would Tom suit the ‘well-regulated’ demands of this prestigious institution? He had all the ingredients to become a great artist – a technical ability beyond his years, an unwavering self-belief, a sharp mind bursting with ideas, and a quick wit to charm his...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.3.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | femina janina ramirez rule nostalgia hannah rose woods Lucy Worsley jane austen • God’s Traitors Jessie Childs • The Georgians Penelope J. Corfield meet robert peal secret history dan cruikshank • thomas cromwell Tracy Borman • thomas cromwell Tracy Borman, God’s Traitors Jessie Childs • time traveller's guide regency britain ian mortimer lucy inglis Suzannah Lipscomb history • uncrowned queen Nicola Tallis alison weir eleanor of aquitaine |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78578-956-2 / 1785789562 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78578-956-4 / 9781785789564 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich