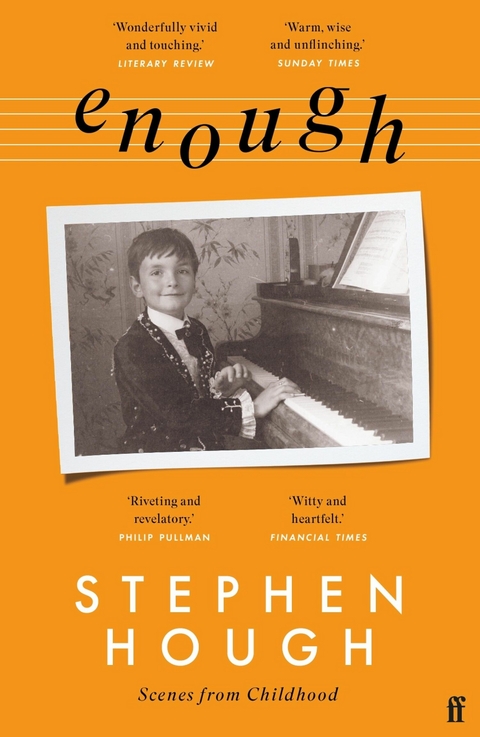

Enough (eBook)

320 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-36291-2 (ISBN)

One of the most distinctive artists of his generation, Stephen Hough combines a distinguished career as a pianist with those of composer and writer. He was named by The Economist as one of Twenty Living Polymaths. He is the winner of numerous awards and was awarded a knighthood in the Queen's Platinum Jubilee Honours 2022. Hough has performed with many of the world's major orchestras and has given recitals at the most prestigious concert halls. He has composed works for orchestra, choir, chamber ensemble and solo piano. Also a noted author, he regular contributes articles for The Guardian, The Times, Gramophone and BBC Music Magazine, and wrote a blog for The Telegraph for 7 years. He lives in London, where he is a visiting professor at the Royal Academy of Music.

'Stephen Hough's memoir had me gripped from the beginning [ .] riveting and revelatory. Most memoirs give me far more than I want to know - this is the rare sort that left me urgently demanding a second volume, a third, a fourth. I loved it.'Philip PullmanStephen Hough is indisputably one of the world's leading pianists, winning global acclaim and numerous awards. This memoir recounts his unconventional coming-of-age story, from his beginnings in an unmusical home in Cheshireto the main stage of Carnegie Hall in New York aged 21. We read of his early love-affair with the piano which curdled, after a teenage nervous breakdown, into failure at school and six-hours a day watching television, engulfed in dreams, seesawing between sexual and religious obsessions.We meet his supportive, if eccentric parents - his artistically frustrated father, his housework-hating mother. We read of the teachers who encouraged and inspired, and others who hit him on the head screaming, "e;you'll do nothing with your life"e;. Then finding his way back to the piano, having abandoned plans for an alternative life as a Catholic priest, he flourished at the Royal Northern College of Music and the Juilliard School, beginning his career as an international soloist as this book ends.

Naughty boy

Chetham’s School has a long history, beginning as a college for the training of priests in the fifteenth century, then becoming a school for ‘poor boys from honest families’ in 1656, and finally the specialist music school it has been for over half a century. The original 1421 building survives as Chetham’s Library where, in 1845, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels met and sat and wrote, giving birth to the Communist Manifesto. Today the school is a place of serious study with a calm, confident vision of what it is trying, and succeeding, to do. It was not always thus.

It is impossible to write about Chetham’s in the 1970s without criticism. To enter the school was to walk through the cobbled sandstone gatehouse, to the right of which were large metal bins where leftovers from lunch were deposited … to feed the pigs, we were told. Thus each day at Chets began with the reek of rotting food. By my second year most classes took place on a bomb site beyond those bins where prefabricated buildings perched, smelling of glue and sawdust, with squeaky doors and loose hinges and the creak of cheap, uncertain floors.

I began in the senior school in the autumn of 1972 and, to be frank, the place was a mess – physically, academically and (often) musically. My time there all but destroyed me and I left with a barely usable set of barely mediocre O levels. The facilities at the school in those days were dire. The chemistry lab seemed as medieval as the library. I think there were five or six Bunsen burners, although not all of them worked. ‘What are those crystals over there, sir?’ We pointed at a spider’s web obscuring the copperplate writing on the cloudy, dusty glass bottles. And then there were the practice rooms in Palatine House. One of them had such a large hole in the brick wall that it was literally possibly to climb through into the next room. The banisters on the stairwells leading up to those studios would, with a gentle pull, lift out of their sockets, exposing a three-floor drop down. Everything hung loose, let in draughts, wobbled, peeled, stuck. I don’t believe in ghosts but this building seemed cursed with a terrible melancholy. It had originally been built in 1843 as one of the first railway hotels, servicing nearby Victoria station. Even as a schoolboy I could imagine its past, sad residents, alone in the small rooms, travelling salesmen staring hopelessly out of the sooted windows at the desolate industrial landscape.

Let me admit though, before going any further, that I was not blameless in my underachievement at Chetham’s – and Marc Bolan might have had something to do with my distractions. I was often naughty in class and would sit at the back passing notes around, trying to make my fellow students laugh. I would frequently be sent out, along to the headmaster’s office in disgrace. I would ask outrageous questions or offer outrageous subjects for discussion. I remember tracing the word WOW on the chalkboard with the point of a compass. Little did I realise that when the board would next be dusted clean of the ‘causes of the French Revolution’ that 1970s word of exclamation would shout out with a chalky white splendour. ‘Who did this?’ demanded the teacher. Well, at least I owned up. Sent out once more.

Random teachers

I was at Chetham’s during its most dysfunctional and (as we now realise) criminal period. Although there were some very good teachers (Ian Little, Trevor Donald, John Leech, Robert MacFarlane, Michael Asquith spring to mind), most of them seemed to have come from some catalogue of misfits, eccentrics and (I will no longer be hit over the head for saying so) sadists.

Mr Raby was the deputy head who also taught maths – often with one of his basset hounds (Hugo or Humphrey) lying on top of the desk in front of him licking its genitalia. He had a strange walk with a bobbing upper-body movement like some giant, tweed-jacketed pigeon – always a pipe leaving clouds of smoke in his trail, always dressed in tobacco-brown clothes. Once, when I fell down the stairs (I was seeing if I could hop down on one leg – I couldn’t), he took me into his office and I saw a kindness in him that I’d never seen before. He made me a mug of tea to overcome the shock and forced me to drink it with lots of sugar: ‘You’re having a cup of tea whether you like it or not,’ he said with a brown-toothed smile.

Mrs Jones taught us General Studies. She was a kind, caring soul but we made terrible fun of her, pushing the envelope to the edge. I did a project on James Joyce’s Ulysses once, reading out my essay in front of the class as a short presentation. I’d chosen the fruitier passages, planning to declaim about the ‘scrotumtightening sea’, but I got no further than ‘James Joyce was born in …’ before being reduced to hysterical laughter. I made about four attempts without making it to Dublin, each time more helpless, and Mrs Jones, in a rare moment of anger, told me to sit down. Just as well, as I hadn’t even read the book – and still haven’t to this day. And I avoid swimming in the sea at all costs.

Ian Little was my English teacher for most of the five years I spent at Chets. I remember illuminating classes on The Crucible and A Kestrel for a Knave (though why did we spend so much time on such a thin book?), but above all I was conscious that he was on my side with patience and high marks when I occasionally pushed outrageousness to the limits. Once we were given a random word to write an essay on – mine was ‘bacon’. I went into sixth gear on a roller-coaster of smashed-up grammar with a surging cross-current stream of consciousness (‘it is pink yes it is pink slice it up my bacon just sit on the rasher’). I don’t think my piece was very good but somehow he sensed there was a sizzle there worth encouraging.

I still remember the haiku lesson when he stood with a piece of chalk in his hand, silent, thinking for quite a number of seconds, then wrote out the following:

A haiku consists

Of five, seven and of five:

Of what, I wonder?

Stanley Jones was my first teacher there, before I was moved up a year to first-form senior school. He was musically inclined and gentle, always smelling of Pears soap. He had a strange nervous laugh that would suddenly engulf him and made him seem sad – it was an explosive guffaw that switched on, and then off. Much later I knew him as a bitter, tragic old man, refusing visits except occasionally from young men he’d met who would come to give him massages. He was always very kind to me, though, and before his decline he was a frequent visitor to our house. He’s the unnamed person in my book Rough Ideas who told me my playing was ‘dreadful’ but who, in so doing, changed the direction of my pianistic life. He’d invite boys over to his house in Didsbury for a ‘Guinness and cheese’ lunch. It sounded like a euphemism but actually, on the one occasion I went, he did just offer me food and drink. He’d put Delius on the record player and as the sonorous harmonies would swamp his musty study his eyes would fill with tears. He was a man of great sensitivity who never seemed to have found a healthy way to express it.

Donald Clarke taught a number of subjects, including the piano, but in the one sex education class I remember him taking he was unable to face talking about the human body. I still remember his awkwardness, his fidgeting, his cracking voice, his blushing cheeks. He couldn’t have been more embarrassed if he’d been acting out the sexual intercourse he was trying to describe instead of talking about it. Somehow I remember a ferocious temper too, very rarely displayed but terrifying when it was.

Another teacher taught another subject – I will leave the details vague as it is neither helpful nor pleasurable to say more. ‘You’re useless. You’ll do nothing with your life,’ he once screamed at me as he strode to the back of the classroom to strike me forcefully across the head, as if to make sure my brain would not have the capacity to contradict him. He was a pitiful character, tall and gawky with no self-control. One occasion was quite horrifying. The class was making fun of him yet again and somehow things got out of hand. At the high point of the commotion he let out an immense roar: ‘Will you just STOP it!’ On the word ‘stop’ he flung his hand up into the air in emphasis and hit it with tremendous force against a light fitting, his roar of anger turning into a roar of pain. The class erupted in laughter and he burst into tears, a total wreck of a man. Children will always be cruel, but for a teacher self-control comes before crowd control. An ability to laugh at himself, to deflate the situation by a change of mood, to turn things around, a light touch … he had none of them and suffered (how he must have suffered!) as a result.

Penry Williams, our history teacher, was wiser. He was also subject to some teasing (he had a lisp, a light covering of wispy blond hair and a limping leg – he would frequently trip over someone’s briefcase or a chair or a desk) but as he...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.1.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Klassik / Oper / Musical | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Schlagworte | Carnegie Hall • concert pianist • grand piano • Juilliard • Pianist • Priest • Royal Northern College |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-36291-5 / 0571362915 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-36291-2 / 9780571362912 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich