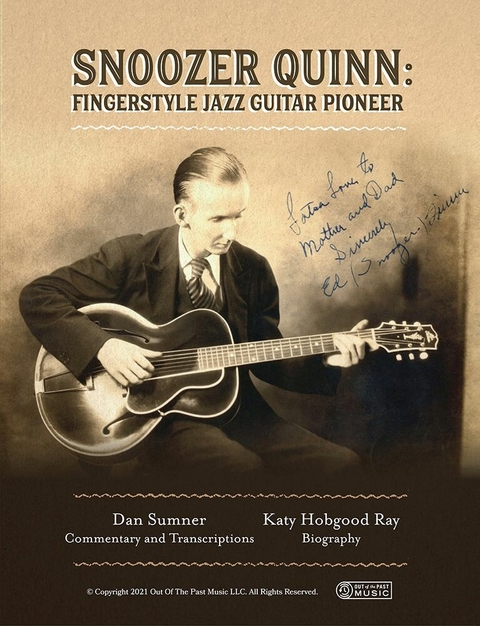

BIOGRAPHY:

PERSONAL INTRODUCTION BY KATY HOBGOOD RAY

I grew up in a large family that loved to gather around the parlor piano to sing and circle the campfire with guitars. I have always felt a connection to my family through music. As a child, I loved to hear my elders sing the songs they’d loved as kids, and to hear them tell stories about the past. I’ve always had a deep curiosity for both music and family history.

Songs and stories stuck with me, including those told on my dad’s side about an uncle who had the marvelous nickname of “Snoozer.” Eddie “Snoozer” Quinn was from Bogalusa, Louisiana, where I was born (like my dad and my grandparents). Snoozer was a musical genius who could play any instrument he touched, they said, and had toured with many famous musicians. He played violin like angels singing, said Aunt Nancy, and watching him play guitar would make your jaw drop. Supposedly, Snoozer could shake your hand while playing guitar and never miss a beat!

Years later, I realized that Snoozer’s abilities were more than a family memory. Around 2001, while living in Shreveport, Louisiana, I was singing jazz standards in a band that included fingerstyle guitarist Steve Howell. Steve has an immense knowledge of country blues and early jazz figures. I thought to amuse him with the story of my distant relative named Snoozer Quinn.

Much to my surprise, Steve knew of Snoozer, and even schooled me on how important Snoozer’s legacy was to early jazz guitar. A few weeks later, Steve gave me an incredible gift: a framed photograph of Snoozer Quinn and Louis Armstrong. I was floored. It was the first time I had ever seen a photo of Snoozer, and here he was, captured in laughter with the legendary Louis Armstrong. The photograph belonged to the collection of the Shreveport Federation of Musicians, chapter 116 of the AFM.

In 2004, I started graduate school at Tulane University. There, nestled in the “cradle of jazz” and surrounded by knowledgeable New Orleans jazz experts, I was in a prime position to learn about Snoozer’s career. I began to explore Bogalusa and met my Quinn cousins. Most notably, I connected with Terry “Foots” Quinn who is Snoozer’s most directly surviving relative (nephew, son of Alton Quinn) and who was keeper of the Snoozer archive of instruments, photographs, and memorabilia.

Snoozer is a figure that people are hungry to know more about. I have had the warm and enthusiastic support of a community of musicians and jazz musicologists, such as Chip Henderson, John Joyce, Bruce Raeburn and Lynn Abbott at the Hogan Jazz Archive, and others such as Tom Stagg, Jack Stewart, John Rankin, Carolyn Kolb, Charles Chamberlain, Ann Woodruff, John McCusker, and Greg Lambousy and Beth Sherwood at the Louisiana State Museum.

I’ve felt great serendipity and synchronicity in my search for Snoozer, which has ebbed and flowed as the years go by. As my own life has changed direction, I’ve been bouncing around to places that were significant to Snoozer. He had a life in all the cities I have lived in: Bogalusa, Shreveport, New Orleans—even Houston, Texas and Memphis, Tennessee! It’s been a pleasure to connect with him through music, through place, and through people.

My search for Snoozer’s music has enriched my life in countless ways. It’s led me to rediscover my roots in Bogalusa and reconnect with distant relatives. (Foots and I have formed a strong friendship and have collaborated on several music projects featuring his original folk songs.) I’ve met and interviewed many fascinating people as I sought to learn more about Snoozer’s influence, such as great guitarists Les Paul and Frank Federico. My search has taken me into lively jazz clubs, quiet nursing homes, grand university archives, mildewy basements of crumbling houses, and ramshackle cemeteries. I’ve sat for untold hours scrolling through microfilm and thumbing through stacks of 78s, ever hopeful for a miracle. I have not yet uncovered all I hope to unearth, but I have found tantalizing bread crumbs that keep me searching even as the light grows dim.

I am grateful to Steve Howell for lighting the match on this long-burning torch I carry, and for helping me share Snoozer’s story today. I hope that this release of the hospital recordings, along with the musical explication by guitarist Dan Sumner, will bring about more interest in Snoozer, whose legend for too long has been shrouded in mist.

SNOOZER’S LEGEND

I met Quinn, the only boy who has it on Eddie Lang, I believe. - Frankie Trumbauer

Snoozer Quinn is the best [guitarist] of all time. - Danny Barker

I visited Snoozer at his house.…That’s where I learned to pull and hammer strings.- Les Paul

Eddie “Snoozer” Quinn, a pioneer of early jazz guitar, can be found in memoirs, diaries, and oral histories of some of the earliest jazz musicians. Born in 1907 in McComb, Mississippi, Quinn has been called a missing link between country blues guitarists like Big Bill Broonzy and early jazz guitar soloists like Eddie Lang.

In his peak career days, in the late 1920-1930s, Quinn performed with some of the biggest names in early jazz—such as Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Teagarden, Paul Whiteman, and the Dorsey brothers. On April 30, 1948, Quinn was inducted into the National Jazz Foundation in New Orleans,

1 along with Louis Armstrong and Stella Oliver, widow of Joe “King” Oliver.

2 New Orleans banjoist and guitarist Danny Barker considered Quinn “the best of all time.”

3Yet Snoozer Quinn is overlooked in the majority of jazz anthologies and merely footnoted in guitar history books. Working in the days before guitar amplification, Quinn was an acoustic sideman in the era of big band jazz. His technical skill on a quiet instrument was buried beneath the sound of horns and a full rhythm section. Though Quinn made a number of professional jazz recordings in his prime, many of these sessions were never released and are now lost—such as a solo session recorded for Victor in 1928 and a Columbia session with Bix Beiderbecke and Frankie Trumbauer in 1928. Of the professional recordings that are available, Quinn is playing as accompaniment in big orchestras or to vocalists such as Bee Palmer.

Anecdotes of Quinn paint a vivid picture of an unusual looking man. Slightly deformed from birth, Quinn had an egg-shaped head and was blind in one eye. He was reportedly quiet and shy. Tragically, Quinn struggled with alcoholism and suffered from chronic illness from an early age, and began entering hospitals for extended periods of time before he turned 30 years old. Due to all these factors, Quinn’s career was short. He died of tuberculosis at age 42, in 1949.

Even so, the sparse information known about Quinn has passed through generations of serious guitar players like a whispered mythology and a shared secret. The great guitarist and inventor Les Paul, in his youth, drove out of his way to Bogalusa, Louisiana to seek Quinn out for consultation—at Bing Crosby’s urging. Leo Kottke told

Frets Magazine in 1987: “Snoozer was playing what a lot of us today are trying to play, which is a finer approach to the guitar, but with all of the available harmony.”

4Quinn’s fabled abilities have only grown more mysterious with the passage of time. Multiple accounts attest that Quinn could play several parts on a guitar at once, and do it playing with one hand. The hillbilly singer (and Louisiana Governor) Jimmie Davis, whom Quinn accompanied on a 1931 recording session for Victor, said, “The last time I saw [Snoozer Quinn], he was walking down the streets of Baton Rouge, playing the “Tiger Rag” — had the guitar on his back, playing it back behind him, see.”

5But where does the myth end and the truth begin? What was Quinn was capable of in his prime, and just what role did he have in the evolution of jazz guitar as a solo instrument? What was Quinn playing in the 1920s that so captivated and impressed his fellow jazz musicians, yet was deemed unmarketable by record company executives? What was it about Quinn’s musicianship that made Paul Whiteman hire him on the spot? What was it about Quinn’s technique that thrilled his fellow musicians?

Although there are no clear recordings of Quinn in his prime to work from, we are incredibly fortunate that in 1948, he was recorded by his longtime friend and bandmate Johnny Wiggs. A cornetist and New Orleans educator who recognized the importance of capturing Quinn’s guitar work for posterity, Wiggs recorded Quinn on acetate cutting machine inside the tuberculosis ward at a hospital in New Orleans. Though Quinn was gravely ill at the time of recordings (he died within months of the session), the recordings offer insight into his musicality and unusual technique.

Wiggs has described the recording session in several accounts. Here is how he described it to jazz historian William Russell:

He was.…in this little room, about 6 by 10 foot. I was trying to operate the recording machine, keep some of the thread from messing up the needle, keep people out of the room, and play, all at the same time. During one number the telephone started ringing, so I had to throw the phone off the hook.…I didn’t want to tire Snoozer as he was pretty weak then.…He’d been working with an amplified guitar a lot and I...