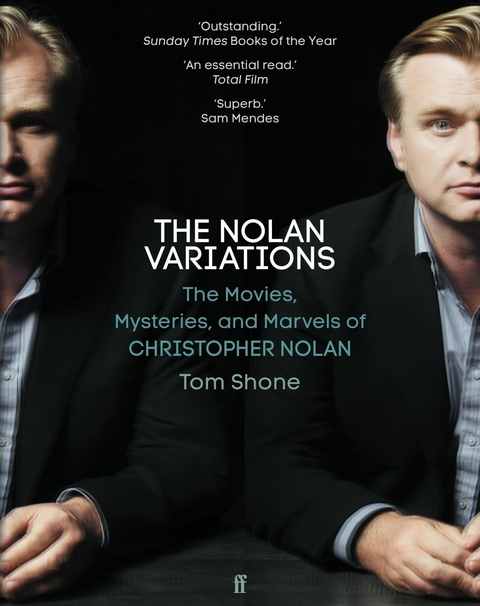

Nolan Variations (eBook)

288 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-34800-8 (ISBN)

Tom Shone was the film critic of the Sunday Times from 1994 until 1999. He is the author of five books, including Tarantino: A Retrospective and Martin Scorsese: A Retrospective. His writing has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, the Times Literary Supplement, IntelligentLife and Vogue. He currently teaches film history and criticism at New York University.

A rare, intimate portrait of Hollywood's reigning 'blockbuster auteur' whose deeply personal billion-dollar movies have established him as the most successful director to come out of the British Isles since Alfred Hitchcock. 'A masterclass . . . brilliant. Immersive, detailed, meticulous, privileged inside-dope.' - Craig RaineMore than just the tinkerings of a glass watchmaker, Christopher Nolan's films have an unerring grasp of the way time makes us feel. Time steals people away in his films, and he takes careful note of the theft. Time is Nolan's great antagonist, his lifelong nemesis. He seems almost to take it personally. Written with the full cooperation of Nolan himself, who granted Tom Shone access to never-before-seen photographs, storyboards and sketches, the book is a deep-dive into the director's films, influences, methods and obsessions. Here for the first time is Nolan on his dislocated, transatlantic childhood, how he dreamed up the plot of Inception lying awake one night in his dorm at school, his colour-blindness and its effect on Memento, his obsession with puzzles and optical illusions - and much, much more. Written by one of our most penetrating critics, The Nolan Variations is a landmark study of one of the twenty-first century's most dazzling cinematic artists. 'Christopher Nolan is a wonderfully unlikely contemporary filmmaker. We're fortunate indeed to have him, and fortunate now to have this book.' - William Gibson

Tom Shone was the film critic of the Sunday Times from 1994 until 1999. He is the author of five books, including Tarantino: A Retrospective and Martin Scorsese: A Retrospective. His writing has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, the Times Literary Supplement, Intelligent Life and Vogue. He currently teaches film history and criticism at New York University.

lt;b>Christopher Nolan is a wonderfully unlikely contemporary filmmaker. We're fortunate indeed to have him, and fortunate now to have this book.

A MAN WAKES UP in a room so dark that he cannot see his hand in front of his face. How long he has been sleeping, where he is, or how he got there he does not know. All he knows is that the hand he is holding in front of his face is his right hand.

Swinging his feet out of the bed, he places them on the ground, which is cold and hard. Maybe he is in the hospital. Has he been hurt? Or maybe a barracks. Is he a soldier? With his fingers, he feels the edge of the bed—metal, with rough wool sheeting. A memory comes back to him—of cold baths, a bell ringing, and a dreadful feeling of being late—but just as quickly the memory is gone, leaving him with a piece of knowledge: a light switch. On the wall somewhere. If he can just locate this switch, then he will be able to see where he is and everything will come back to him.

Gingerly, he pushes one foot across the floor, his sock snagging on something: splintery wood. Floorboards. These are floorboards. He takes a few steps forward, feeling his way with outstretched arms. His fingertips brush a cold, hard surface of some kind: the metal frame of another bed. He is not alone.

Feeling his way around the end of the second bed, he triangulates its position with respect to his own and determines where he imagines the central aisle of the room to be. Then he proceeds to inch down it, hunched over to better feel the way. It takes him several minutes—the room is a lot longer than he thought—but eventually he comes up against a wall, the plaster cool to the touch. Flattening himself against it, he spreads his arms wide, catching a few flakes of plaster with his fingertips, and, with his left hand, finds the light switch. Bingo. With one flick of the switch, the room is bathed in light and he knows instantly where and who he is.

He does not exist. He is a hypothetical figure in a thought experiment by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. In a 1786 essay entitled “What Does It Mean to Orient Oneself in Thinking?” Kant attempted to determine whether our perception of space is an accurate reflection of something “out there” in the universe, or an a priori mental apprehension, something intuited “in here.” A former geography teacher, he was well placed to address the matter. Just a few years earlier, the invention of the telescope by his countryman William Herschel had led to the conception of “deep sky” and the discovery of Uranus, while the invention of the hot-air balloon had spurred mapmakers to new advances in meteorology and the understanding of cloud formation. It was to their example that Kant looked first. “If I see the sun in the sky and know it is now midday, then I know how to find south, west, north, and east,” he wrote, “even the astronomer—if he pays attention only to what he sees and not at the same time to what he feels—would inevitably become disoriented.” Kant thus posited the example of a man who was awakened in a strange room, unsure which way he was facing. “In the dark I orient myself in a room that is familiar to me if I can take hold of even one single object whose position I remember,” he said, “and if someone as a joke had moved all the objects around so that what was previously on the right was now on the left, I would be quite unable to find anything in a room whose walls were otherwise wholly identical.” Left and right are not something we are taught or observe. It is a priori knowledge that we simply wake up with. It derives from us, not the universe, and yet from it flows our entire apprehension of space, the universe, and our place within it. Unless some joker has been tampering with the light switch, in which case all bets are off.

The career of the film director Christopher Nolan has spanned no less convulsive a period of technological change than Immanuel Kant’s. In August 1991, Nolan’s second year at University College London, the World Wide Web was launched by Tim Berners-Lee on a NeXT computer at the European Organization for Nuclear Research. “We are now living on Internet time,” said Andrew Grove, chief executive of Intel, in 1996. In 1998, the year Nolan released his first film, Following, U.S. vice president Al Gore announced a plan to make the GPS satellites transmit two additional signals for civilian applications, and Google was launched with the Faustian mission “to organize the world’s information.” A year later came wireless networking, Napster, and broadband, just in time for Nolan’s second feature, Memento. By the time of his third movie, Insomnia, in 2002, the world’s first online encyclopedia, Wikipedia, had arrived. In 2003, the anonymous bulletin board 4Chan was launched, quickly followed in 2004 by the first source-agnostic social media platform, Facebook, and then by YouTube and Reddit in 2005. “It’s hard to overstate the flabbergasting speed and magnitude of the change,” Kurt Anderson has written. In the early 1990s, less than 2 percent of Americans used the Internet; by 2002, less than a decade later, most Americans were online, overseeing the biggest shrinking of our conception of distance since the invention of the steam engine. With Euclidean space fragmented by the simultaneity of the Internet, time has become the new metric of who is available, but rather than unite us, it has made us aware as never before of the subjective bubble of time in which we each sit. “People ‘stream’ music to us and video, the tennis match we’re watching may or may not be ‘live,’ the people in the stadium watching the instant replay on the stadium screen, which we see repeated on our screen, may have done that yesterday, in a different time zone,” writes James Gleick in Time Travel: A History. “We reach across layers of time for the memories of our memories.”

A simpler way of putting this is that our lives have become a Christopher Nolan movie. Like the maze that adorns the logo of his production company, Syncopy, Nolan’s movies have entrances that are clearly marked. You probably have seen them advertised on TV. They are likely playing in your neighborhood multiplex. They occupy traditional genres like the spy thriller or heist movie. Many of them begin with a simple shot of a man waking up from a dream, like Kant’s hypothetical subject. The world around them is heavily textured, solid to the touch, lent granular texture by immersive IMAX photography and enveloping sound design. The evidence of our eyes and ears compels our investment in this world, this hero, as the familiar tropes of genre filmmaking—heists, car chases, shootouts—surface around him in alien, unfamiliar configurations. The streets of Paris fold back on themselves like origami. An eighteen-wheel truck flips like a beetle. Planes are upended mid-flight, leaving the passengers clinging to the now perpendicular chassis. Some joker seems to be playing with the light switch. Looped narrative schemes and shattering second-act twists further rock the ground beneath our feet, lending the otherwise solid narrative architecture a gauzy metafictional shimmer, as all we had thought solid melts into air, resulting in a delighted astonishment in the audience, which is a million miles away from the bluster and bombast of a typical Hollywood blockbuster. Enlivened by the unshakable sense of a great game being afoot, of having engaged in delicious conspiracy with the film’s maker against the Punch and Judy shows that pass for entertainment on screens elsewhere, we wander dazed out onto the street, still debating the ambiguity of the film’s ending or the Escher-like vertigo induced by its plot. Easy to enter, Nolan’s films are fiendishly difficult to exit, ramifying endlessly in your head afterward like plumes of ink in water. The film we have just seen cannot be unwatched. It isn’t even really over. In many ways, it has only just begun.

Nolan when I first met him in 2000, on the eve of Memento’s release.

*

I first met Nolan in February 2001 at Canter’s Deli on North Fairfax Avenue, not far from the Sunset Strip in L.A. The director’s second film, Memento, had just earned great reviews at Sundance, after a long, anxious year spent trying to secure distribution. A devilishly structured neo-noir with the eerie, sunlit clarity of a dream, Memento concerns an amnesiac trying to solve the case of his wife’s death. Everything up to that point he can remember; everything after he loses every ten minutes or so—a discombobulation mirrored by the film’s structure, which unspools backward before our eyes, plunging the audience into a permanent state of in medias res. It seemed almost blasphemously smart in a way that made you wonder how it might fare, exactly, in a film landscape typified that year by the likes of Dude, Where’s My Car? The film’s knack for winning fans but not distribution had become something of an open secret in Hollywood after a screening the weekend of the 2000 Independent Spirit Awards, at which Nolan had been turned down by every distributor in town with some variation of “This is great,” “We love it,” “We really want to work with you,” and “But this is not for us.” Director Steven Soderbergh was moved to comment on the website Film Threat that the film “signaled the death of the independent movement. Because I knew before I saw the film that everyone in town had seen it and declined to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.11.2020 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Schlagworte | Christopher Nolan • Inception • Martin Scorsese • Memento • Tenet • The Dark Night • The Prestige |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-34800-9 / 0571348009 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-34800-8 / 9780571348008 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 23,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich