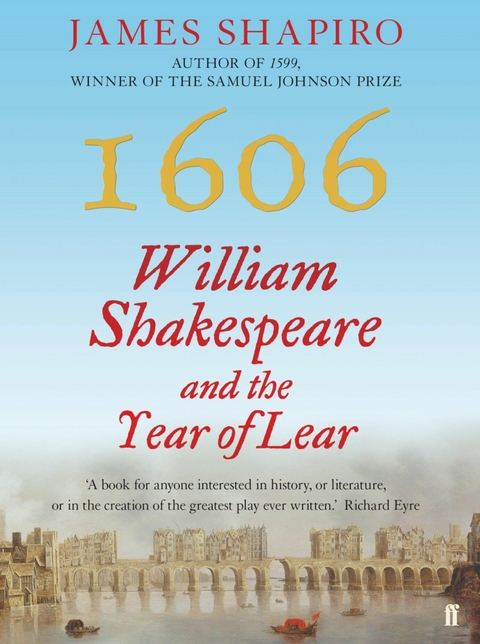

1606 (eBook)

352 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-28385-9 (ISBN)

James Shapiro, who teaches English at Columbia University in New York, is author of several books, including 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (winner of the BBC4 Samuel Johnson Prize in 2006), as well as Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? He also serves on the Board of the Royal Shakespeare Company

1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear traces Shakespeare's life and times from the autumn of 1605, when he took an old and anonymous Elizabethan play, The Chronicle History of King Leir, and transformed it into his most searing tragedy, King Lear. 1606 proved to be an especially grim year for England, which witnessed the bloody aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot, divisions over the Union of England and Scotland, and an outbreak of plague. But it turned out to be an exceptional one for Shakespeare, unrivalled at identifying the fault-lines of his cultural moment, who before the year was out went on to complete two other great Jacobean tragedies that spoke directly to these fraught times: Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra. Following the biographical style of 1599, a way of thinking and writing that Shapiro has made his own, 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear promises to be one of the most significant and accessible works on Shakespeare in the decade to come.

Professor James Shapiro, who teaches at Columbia University in New York, is the author of Rival Playwrights, Shakespeare and the Jews, and Oberammergau: The Troubling Story of the World's Most Famous Passion Play. 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare won the BBC FOUR Samuel Johnson Prize in 2006. His most recent book is Contested Will.

Shakespeare’s portrait, by Martin Droeshout

On the evening of 5 January 1606, the first Sunday of the new year, six hundred or so of the nation’s elite made their way through London’s dark streets to the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace. The route westward from the City, leading past Charing Cross and skirting St James’s Park, was for most of them a familiar one. Many had already visited Whitehall over a half-dozen times since Christmas, the third under King James, who had called for eighteen plays to be staged there this holiday season, ten of them by Shakespeare’s company. They took their places according to their status in the seats arranged on stepped scaffolds along three sides of the large hall, while the Lord Chamberlain, white staff in hand, ensured that no gate-crashers were admitted nor anyone seated in an area above his or her proper station. King James himself sat centrally on a raised platform of state facing the stage, surrounded by his closest entourage, his every gesture scrutinised, rivalling the performers for the crowd’s attention.

This evening’s entertainment was more eagerly anticipated than any play. They were gathered at the old Banqueting House to witness a dramatic form with which conventional tragedies and comedies now struggled to compete: a court masque. With their dazzling staging, elegant verse, gorgeous costumes, concert-quality music and choreographed dancing – overseen by some of the most talented artists in the land – masques under the new king were beyond extravagant, costing an unbelievable sum of £3,000 or more for a single performance. To put that in perspective, it would cost the crown little more than £100 to stage all ten of the plays Shakespeare’s company performed at court this Christmas season.

The actors in this evening’s masque, aside from a few professionals drawn from Shakespeare’s company, were prominent lords – and ladies too. The entertainment thus offered the added frisson of watching women perform, for while they were forbidden to appear on London’s public stages, where their parts were played by teenage boys, that restriction didn’t apply to court masques. Those lucky enough to be admitted to the Banqueting House saw young noblewomen perform their parts in breathtaking outfits designed by Inigo Jones, bedecked in jewels (one onlooker reported that ‘I think they hired and borrowed all the principal jewels and ropes of pearl both in court and city’). For many of these women, some of whom had commemorative paintings done of them wearing these costumes, this chance to perform in public would be one of the highlights of their highly constrained lives.

The building in which they performed was perhaps the only disappointment. Back in 1582, when the Duc d’Alençon had come courting, Queen Elizabeth had ordered that a temporary Banqueting House be constructed in time for his reception. From a distance the large building, ‘a long square, 332 foot in measure about’, looked imposing, constructed of stone blocks with mortared joints. But as visitors approached they would have seen that trompe l’œil painting disguised what was actually a flimsy structure, built of great wooden masts forty feet high covered with painted canvas. As the years passed, Elizabeth saw no reason to waste money replacing it with something more permanent, and by the time that James succeeded her, the temporary frame that had stood for a quarter-century was in disrepair.

Shakespeare knew the old venue well and had played there fourteen months earlier on 1 November 1604, when his last Elizabethan tragedy, Othello, had had its court debut. Over the years he had performed often at Whitehall and would have recognised many of those in attendance. We can tell from the impact this masque had on his subsequent work that Shakespeare had secured for himself a place in the room that January evening. There probably wasn’t a better vantage point for measuring the chasm between the self-congratulatory political fantasy enacted in the masque and the troubled national mood outside the grounds of James’s palace. Insofar as most of his plays depict flawed rulers and their courts, he may have been as intent on observing the scene playing out before him as he was on viewing the masque itself.

The new king hated the old building; it was one more vestige of the Tudor past to be swept away. A few months after this masque was staged James commanded that it be pulled down and a more permanent, ‘strong and stately’ stone edifice, befitting a Stuart dynasty, be built on the site. In the short term, while there was little he could do about its rotting frame, James could at least replace Elizabeth’s unfashionable painted ceiling. She favoured a floral and fruit design; he had it re-covered with a more stylish image of ‘clouds in distemper’.

King James was no less committed to repairing some of the political rot his predecessor had left behind, and this evening’s masque was part of that effort. Five years had passed since Queen Elizabeth had put to death her one-time favourite, the charismatic and rebellious Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex. His execution still rankled with Essex’s devoted followers and their further exclusion from power and patronage under James had left them bitter and alienated. Essex had left behind a young son, now fourteen, who bore his name and title, around whom they might rally. Essex’s militant followers had to be neutralised in order to forestall division within the kingdom. But James couldn’t simply restore them all to favour (as he had with the most prominent of them, the imprisoned Earl of Southampton), even if there were enough money, offices and lands to do so, for that would unsettle the balance of favourites and factions at court. And he couldn’t imprison or purge them all either. That left one solution: binding enemies together through an arranged marriage. James would play the royal matchmaker, marrying off Essex’s son, now a ward of the state, to Frances Howard, the striking fifteen-year-old daughter of the powerful Earl of Suffolk, who had served on the commission that had sentenced Essex to death. That evening’s masque, intended to celebrate their union, doubled as an overt pitch for the political union of England and Scotland, a marriage of the two kingdoms that James eagerly sought and knew that a wary Parliament would be debating later that month.

Though he was now the most experienced dramatist in the land, Shakespeare had not written the masque and, had he been invited to do so, would have said no. It would have been a tempting offer. If he cared about visibility, prestige or money, the rewards were great; the writer responsible for the masque earned more than eight times what a dramatist was typically paid for a single play. And on the creative side, in addition to the almost unlimited budget and the potential for special effects, the masque offered the very thing he had seemingly wished for in the opening Chorus to Henry the Fifth: ‘princes to act / And monarchs to behold the swelling scene’ (1.0.3–4). That Shakespeare never accepted such a commission tells us as much about him as a writer as the plays he left behind. There was a price to be paid for writing masques, which were shamelessly sycophantic and propagandistic, compromises he didn’t care to make. He must have also recognised that it was an elite and evanescent art form that didn’t suit his interests or his talents. If this was a typical Jacobean masque, the evening’s entertainment devolved into serious drinking and feasting after the closing dance. By then, I suspect, Shakespeare was already back at his lodgings, doing what he had been doing well into the night for over fifteen years: writing.

Or trying to. For the last few years, certainly since the beginning of the new regime, his playwriting wasn’t going as well as it once had. The extraordinary productivity that had marked his Elizabethan years, when writing three or even four plays in a year was not unusual, now seemed a thing of the past. His sonnets and narrative poems were behind him. So too were twenty-eight comedies, histories and tragedies – though only five of these had been written since he had finished Hamlet at the turn of the century. Things had begun to look more promising with his first effort under the new king, Measure for Measure, finished by 1604, a darkly comic world of court, prison, convent and brothel, starring an intellectual ruler who, like the new monarch, enjoyed stage-managing how things worked out. But another fallow period followed. In the three years since King James had come to the throne Shakespeare had written only one other play, Timon of Athens. With Timon he went back to something that he hadn’t tried since his earliest years in the theatre: working in tandem with another writer. He co-authored this tragedy of a misanthrope – a play about extravagance and its embittering consequences in which the hero, if you can call him that, withdraws from the world and dies cursing – with the up-and-coming Thomas Middleton. It was a smart choice. Middleton, sixteen years younger than Shakespeare, was already a master of those satiric citizen comedies to which sophisticated audiences were flocking. But if the version of that play published in the 1623 folio is any indication, their collaborative effort remained unpolished and perhaps unfinished. Young rivals may well have begun whispering that Shakespeare was all but spent, a holdover from an earlier era whose no longer fashionable plays continued to be recycled at the Globe Theatre and at court.

One of the challenges...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.9.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Lyrik / Dramatik ► Dramatik / Theater |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | 1599 • Antony and Cleopatra • King Lear • Macbeth • Royal Shakespeare Company • Shakespeare Anniversary • The Globe |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-28385-3 / 0571283853 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-28385-9 / 9780571283859 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 12,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich