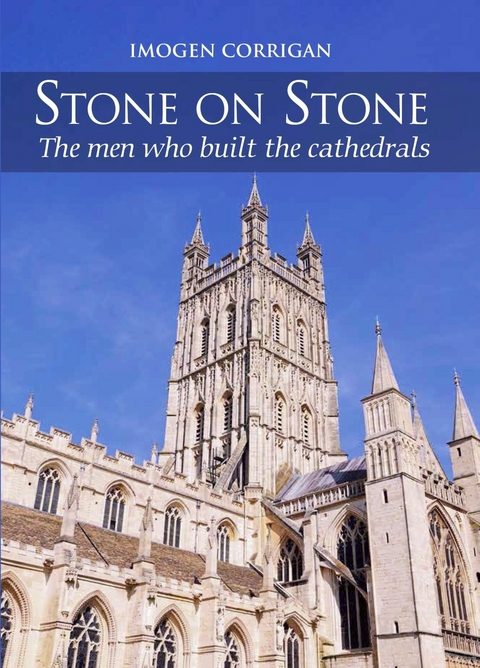

Stone on Stone (eBook)

224 Seiten

Robert Hale Non Fiction (Verlag)

978-0-7198-2799-0 (ISBN)

Imogen Corrigan joined the army straight from school, retiring as a Major after nearly twenty years of service. She then went to the University of Ken to study Anglo-Saxon and medieval history, graduating with first-class honours. She is now a freelance lecturer, travelling and working across Britain and Europe.

CHAPTER ONE

NEW TECHNOLOGY OR NEW SPIRITUALITY?

Establishing the basic shape of a cathedral

BEFORE WE MEET the Master Masons themselves, we need to think about what was at the centre of their being: the cathedral. More especially, we need to consider how the shape of the building developed, which was, after all, critical to the overall plan. In cathedrals and churches, the shape is more important than it might first seem because this affected the spread of the religion. While it is obvious that there cannot be too many variations in the shape of any structure required for public gatherings, the Roman basilica’s internal floor plan was suited to Christian meetings because it was essentially an oblong hall with a rounded apse at the most significant part, for it was within the apse that an altar could be placed.

Figures 1 and 2 show basic layouts for both a basilica and a later Gothic cathedral, and it is plain to see how complex the central design became. Early missionaries as far back as the fourth and fifth centuries AD discovered that a large narthex, or porch attached to the basilica, was an important factor and a useful aid to recruiting: anyone could go inside to shelter from the elements, conduct business or simply meet friends. While they were there, they would be able to hear the strangely soothing and seductive mantras of the liturgy being carried out and, no doubt, smell the incense used more liberally then than now. There would normally be three doorways from the porch into the church through which the curious could stare, although the uninitiated would not be permitted to go into the main part of the building, which was reserved for those fortunate enough to have been saved spiritually. One might imagine the craning of necks and whispering in the outer porch; Christianity was new to many and therefore either exciting or perhaps horrifying. It would be natural for many to feel extremely uneasy about this new religion, as anyone would if asked to discard whatever spiritual practice and belief had been ingrained from childhood. By the fourth century AD, Christianity was now seen as a definite religion as opposed to a group of people following the teachings of a charismatic speaker. Enough people had died for it to make it both interesting and credible. The Emperor Constantine’s embracing it gave it authority and status, and promises of eternal life and/or relief from physical or mental pain had to make it worth a second look.

1 Ground plan for Roman basilica

2 Ground plan for cathedral

Rumours will have circulated in the porch about miracles happening in the name of Jesus Christ and the saints. Local Christian teachers would have sat there, talking to passers-by and the interested and thus this square, almost empty space became a valuable part of the conversion process. In parish churches later, the porch would become the place where civil business was conducted as well as marriage services. It became a space for business for the local community, which is why some later porches are very large, having benches and often niches for statues and holy water to be used in the swearing of oaths. Some porches still have an upper room, which was used for parish meetings and schooling. Given that illustrations have always been an important part of missionary work, stories from the life of Christ or key elements of Christianity would have been painted on the walls or carved over the doorways.

Baptism was the next step. In the ruins of the early Christian basilica at Soli in North Cyprus, which was built in the second half of the fourth century AD, one can see the remains of the baptizing pool just inside the church, immediately beyond the door on the southern side of the porch. In effect, no one could get past without having been admitted to Christianity. To this day, the font is often still placed so close to the main entrance of the church that it is almost an obstacle, a constant reminder of the beginning of the Christian journey, although many congregations have now moved the font to make the baptizing area more central. Once inside the inner building, the newly converted could stand with the others in the areas we know as side aisles. In missionary churches of this style, the aisles would not be open plan and marked with pillars, as they are now, but physically separated by a low wall or fence so that ordinary Christians could see and join in, but not enter. It seems that the congregation could approach as far as the choir area to watch, making the place similar to a theatre with a protruding stage on which the priests would perform. This, again, was an important tool for conversion. There was little enough entertainment for the majority anyway, so the ritual carried out against a backdrop of candlelight, with precious vessels and vestments glinting gold and gorgeous manuscripts glimpsed through a haze of incense, would have been extremely impressive.

In the Roman pagan administrative hall (the basilica), there was often a small room known as a porticus, which was accessed from the inside. Sometimes there were two projecting from each side of the building about two-thirds of the way along. When built for Christian purposes, these became small chapels, or even offices, as can be seen marked out on the ground, for example, beside the remains of the seventh-century church at Bradwell-juxta-Mare on the Essex coast. Much later on, these would be extended into the arms known as transepts, which transform the ground plan of the building into the shape of the cross. Gradually, usage and changes in architectural styles would alter the basic floor plan, but the basilica shape appears to have been an effective starting point. St Augustine of Canterbury, travelling from Rome at the end of the sixth century AD, would have been familiar with the basilica-style layout, although we do not know if he intended to impose it on England. Early Anglo-Saxon churches, especially those in the north of England such as Escomb and the older parts of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow reveal a preference for a narrow, single-celled building. These northern churches are a useful indication as to how things might have been because of the influence of Benedict Biscop, who accompanied Theodore, the incoming Archbishop of Canterbury, from Rome in 668–9, worked with him for a couple of years, and then returned to the north-east where he founded the monasteries of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow. The designs are often disproportionately tall, with steeply pointed roofs almost as though they are an arrow pointing upwards, which might have been part of the plan.

Winning hearts, minds and souls

There is, therefore, no doubt that buildings were used as tools for conversion. They had to be impressive to send out the straightforward message that the Christian God was greater than any other gods. We should remember that what look to us to be relatively small-scale stone buildings would have been more striking at a time when most buildings were constructed out of wood or other organic materials. The great builders in stone – the Romans – had left Britain at the beginning of the fifth century AD so their buildings had by now either fallen into decay or been recycled into town walls. The Anglo-Saxon inclination was to build in wood so, while we look at the tenth-century stone church of St Lawrence at Bradford-upon-Avon in Wiltshire, and marvel at its survival, medieval people would have just looked and marvelled. These comparatively small stone churches would also have towered above the wooden, thatched dwellings of the Anglo-Saxons and most would have been visible from some way off. They would have been something so utterly different on the landscape that the simple fact of their presence would have been remarkable to the passer-by. In modern parlance, the ‘wow’ factor presented by Anglo-Saxon churches is something difficult to imagine in today’s steel-and-concrete built environment. The desire of early Anglo-Saxon Master Masons (and records of a few have come down to us) was not simply to build to the glory of God, but also to provide a roof below which conversion and Christianity could take place – but first the missionary priests had to encourage people to gather below that roof.

It seems likely that the earliest church buildings would have been wooden lean-to arrangements, probably constructed by the priests themselves with local help. But, as Christianity took hold across Britain and Europe, church building progressed from a form of frontier outposts to more impressive monuments to God. The larger ones could attempt to instruct the masses and encourage the priests in a more distinctive way: they could try to recreate Heaven on earth, and this is important. Not only is the Bible peppered with building metaphors, but also with numerous allusions to the Heavenly City. In addition, the Old Testament offers specific details about temple building.1 The Master Masons did not use these references as any form of template – they were too vague – but they will have noted that there are allusions to structured, planned places in the after-life. This was most notable in the New Testament book of Revelations 3 and, especially, Revelations 21, which was often taken as the authority to lavish fortunes on the decoration of cathedrals and churches. Again, a cathedral was not necessarily built to the specifications laid down, but by the time of the eleventh century there was a great desire to get physically closer to God and to try to understand some of the immense mystery surrounding Him. God was seen as being all-powerful, yet also extremely personal: all sins were known and noted. The risk of damnation was great, but the chance of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.12.2018 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 20 colour and black & white photographs 2 line artworks |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Mittelalter |

| Kinder- / Jugendbuch ► Sachbücher ► Naturwissenschaft / Technik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Schlagworte | Abbey • academic books on medeival times • Basilica • bosworth • Building • building cathedrals • building conttrol • Cathedral • cathedral history books' religious buildings • Church • Edward IV • Edward V • Francis Lovell • Gothic Style • Henry VII books • History • Lamber Simnel • Mason • master mason • medeival europe • Medieval • medieval architecture • minster Lovell • perkin warbeck • princes in the tower • religious: worship • Richard III • romanesque style • Stoke • Stone • stone masonry • stone on stone • tudor books • Viscount Lovell • War of the Roses bokos |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-2799-X / 071982799X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-2799-0 / 9780719827990 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich