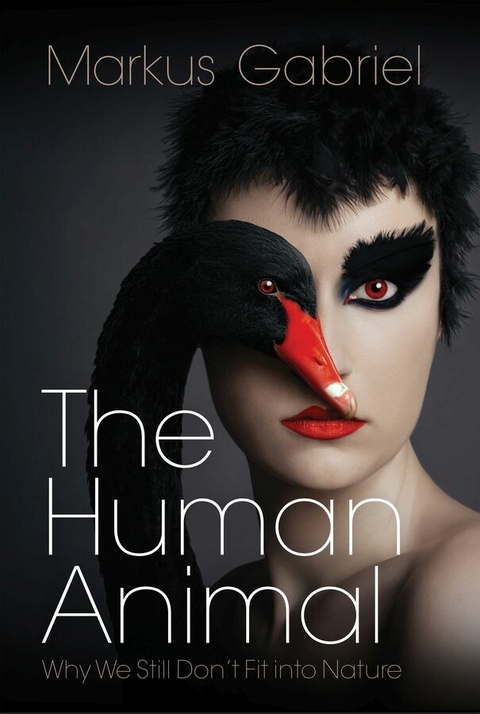

The Human Animal (eBook)

365 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-5804-9 (ISBN)

Markus Gabriel argues that what distinguishes humans from other animals is that humans are minded living beings who seek to understand the world and themselves and who possess ethical insight into moral contexts. Mind is the capacity to lead one's life in the light of a conception of who or what one is. The undeniable difference between us and other animals defines the human condition and places a special responsibility on us to consider our actions in the context of other living beings and our shared habitat. It also calls on us to cultivate an ethics of not-knowing: to recognize that, however much we may seek to understand the world, we will never completely master it. Our grasp of reality, mediated by our animal minds, will always be limited: much is and will remain alien to us, lending itself only to speculation - and to remember this is to stand us in better stead for carving out an existence among the environmental crisis that looms before us all.

Markus Gabriel holds the chair for Epistemology, Modern and Contemporary Philosophy at the University of Bonn and is also the Director of the International Center for Philosophy in Bonn.

Introduction

We find ourselves in a complex crisis scenario. Our habitat, our natural environment as human beings, is threatening to collapse in plain view under the pressure of our modern way of life. Thanks to science and technology, we have rapidly improved our survival conditions. But, by the same means, we have made them worse even more rapidly – a dilemma that is exacerbated with every contemporary crisis.

In the meantime, the civilizational model of modernity, which consists of bringing the resource problems of the survival of our species under control through science and technology, has brought us to the brink of self-extermination. Our instruments of natural and social domination (nuclear power, automobiles, airplanes, smartphones, artificial intelligence, weapons systems, the internet, etc.) are turning against us. It is almost paradoxical. Our technological knowledge, thanks to which we have the internet, AI and social networks, is also the reason why fake news, propaganda and conspiracy ideologies are spreading like wildfire. Through automobiles, airplanes and our fossil fuel way of life, we are better connected than ever and able to interact with spatially distant cultures and people. And yet through these same means we are also destroying our shared environment and our sense of a shared reality.

It is pointless to try to cope with the complex crisis situation of late modernity in which we find ourselves by doing more of the same.1 What we need instead is a reorientation of our image of the human being and our place in nature. That is what this book is about.

Its point of departure is a radicalization of the insight that we humans are animals. The French philosopher Corine Pelluchon has sharpened this point in a series of books with the concrete demand for a new New Enlightenment, at the center of which stands the human animal.2

This New Enlightenment, to which in the meantime many global thought leaders on all continents are committed,3 starts not with reason in general but, rather, with our nature. It is essential to bring ourselves as minded living beings, i.e. as whole human beings, back into the center. We have unjustly distanced ourselves from this center in favor of a mechanistic conception of the world as a structure that can ultimately be controlled and predicted.

This, in turn, raises an old question that we have to ask ourselves again: What does it actually mean to regard humans as animals?

This question is so important because our self-image as animals makes a significant contribution to the socio-political steering mechanisms of the present and future. We can easily see this in the way we deal with pandemics and other natural disasters: disease and (human-induced) climate change are perceived as evils that can be avoided in principle, problems which should be technically remedied as quickly as possible. This has not been achieved in the case of SARS-CoV-2, let alone in the case of climate change. So far, we’ve handled both almost exclusively reactively rather than proactively.

Our prognostic models and approaches to solutions fail because of the challenge we face as animals that can never entirely figure out, let alone technically control, their ecological niche. We must therefore free ourselves of the illusion that our guidelines for the time of crisis and catastrophe in which we find ourselves can be obtained merely through yet another combination of science, technology, economics and politics. The daily shifting of the boundaries of knowledge does not consist in the fact that we approach omniscience. We are always learning more about what we don’t know through scientific progress. (This applies to all disciplines, including the humanities and social sciences.) There is no such thing as omniscience. And there is also no meaningful way technocratically to manage the conditions of human survival in complex systems. Life cannot be contained, nor can it be predicted. The recent virus pandemic with its many variants demonstrates this impressively. We only ever know excerpts of our own form of life. The human animal cannot be overcome by technology. Homo Deus, which the famous historian Yuval Noah Harari envisages as the human of the future in his book of the same name, will never arrive.

In fact, this is precisely what was always known, from Socrates to the famous naturalist Carl Linnaeus, to whom we owe our species name Homo sapiens. Because we cannot completely comprehend ourselves, the self-models on which we depend are prone to error. Linnaeus defines the human being by its capacity to form an image of itself. The entry Homo, which Linnaeus assigns to the primates in his system of nature (thereby clearly locating the human being in the animal kingdom), is supplemented by the characteristic of the capacity for wisdom, sapientia, which, according to him, is our summum attributum, our most excellent quality. The human being is defined in this way by the demand to know itself. And so next to the entry “Homo” in his system stands succinctly: nosce te ipsum, know thyself, with which Linnaeus alludes to Socrates. The motto and the task of philosophy is and remains, according to Socrates, “Know thyself (gnôthi sauton)” – a saying of the Delphic oracle, which Socrates associated with wisdom (sophia). Linnaeus merely translates this into Latin. Because they are committed to the love of wisdom, which is a possible translation of the Greek word philo-sophia, philosophers are sought after wherever the question arises of who we, human beings, are.

Philosophy is about self-knowledge. This includes insight into our freedom. As minded living beings, we are free; from this follows the value of autonomy, of responsible action. At present this value is also coming under pressure in the heart of Europe, and elsewhere in the so-called free world. In order to place values such as freedom, equality and solidarity in an appropriate relationship, and thus to regain confidence in the problem-solving competence of liberal democracy, humans as free, minded living beings must once again be brought to the center of society. Freedom is thereby always also social freedom. For we are prosocial creatures, who can do nothing without doing so in association with others. Freedom and society, individual and collective, do not contradict each other. We are not freer when we are alone, for we simply cannot do most of what interests us as human beings without others. Freedom is something we realize together, not something that positions us against each other.

There is much that you and I have in common. At the very least, we share the quality of being human. Therewith we have much else in common. We have desires, hopes and anxieties, and we are embodied as finite, transient living beings. We belong to nature. Modern physics teaches that there are forces and natural laws which determine everything material. Insofar as we are material, embodied as animals, we are no exception to this. Modern biology and human medicine have also shown us that our bodies are “animal”4 on an elementary level and share many basic structures with other living beings.

All living things known to us consist of cells (or, like unicellular organisms, they are identical with a single cell). These in turn consist of building blocks that can be investigated biochemically and physically. These are the issues addressed by what are now known as the life sciences (medicine, biochemistry, molecular biology, bioinformatics, genetics, pharmacology, zoology, nutritional science, neuroscience, etc.), whose subject matter consists of processes and structures of living beings.

In the course of modernity, discoveries about the behavior of humans and other living beings have been added to physics and the life sciences, and today these are being researched in behavioral sciences such as psychology, cognitive science, behavioral economics and sociobiology. It turns out that we as human beings are to a certain extent decipherable and thus controllable on various levels of our existence (from the cell to social formations such as the family, friend group, or even an entire society). Many of the countless decisions we consciously and unconsciously make every day (when we eat breakfast; whom we date; for how long we wash our hands; on which side of the street we walk; whether we fall asleep on our stomach or on our back, etc.) can be scientifically explained by discerning more or less general patterns in them.

The human being is thus accessible from the third-person standpoint,5 as it is called in philosophy; we are an object of natural- and social-scientific research, one object of research among others. The title of this book alludes to this dimension of being human: The Human Animal.

But that is not the end of the story. For in spite of the above-mentioned modern natural-, life- and behavioral-scientific discoveries about the human being as an animal, we feel that we nevertheless do not fit into nature. The human being is not just an animal. The subtitle of the book alludes to this.

We are not just natural phenomena, which one can deduce from the fact that we explain natural phenomena. The explanation of natural phenomena and so also of those aspects of our life which are irrational is, after all, not itself irrational.

This has also been pointed out recently by the famous cognitive scientist Steven Pinker, who reminds us that logic, mathematics and critical thinking are rational and were also used by...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Karl von der Luft |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Schlagworte | are animals logical • are humans animals • are humans part of the animal kingdom • do animals have morals • do animals think • do humans know more than animals • Ecological Ethics • ethics of not-knowing • how do humans fit into the natural world • how much is there left to discover • Liberal Pluralism • mindedness • moral absolutes • New Enlightenment • New Realism • objective ethics • species • specific difference • Uncertainty • value judgement • what sets us apart from animals |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-5804-7 / 1509558047 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-5804-9 / 9781509558049 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 313 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich