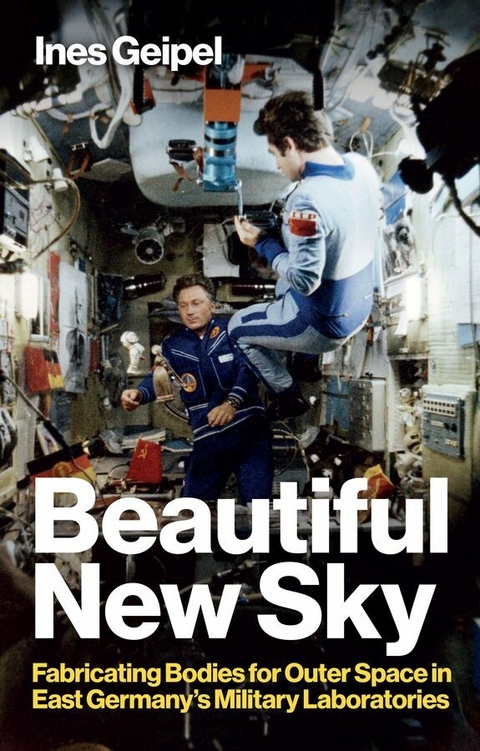

Beautiful New Sky (eBook)

245 Seiten

Polity Press (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6000-4 (ISBN)

Ines Geipel unravels this largely unknown and extraordinary history by delving into East German military records and talking to those who bear the scars of this state-inflicted trauma. Some of the older scientists conducting experiments had already served under the Nazi regime; others threw themselves into collaborating with the Stasi via the military research programme in order to avoid dealing with the war's emotional legacy. Written like a thriller and infused with empathy from someone who had herself experienced the debilitating effects of state-administered doping programmes in the former GDR, this book exposes some of the most disturbing episodes in Germany's recent past.

Ines Geipel is a writer and Professor of Verse Arts at Ernst Busch Academy of Dramatic Arts in Berlin.

It was a bold, ambitious and wildly arrogant idea: extending the reach of communism into space. Spurred on by the defeat of Hitler and the competitive rivalry with the United States, the Soviet space programme saw a frenetic surge of scientific activity focused on the objective of demonstrating Communist mastery beyond the confines of the Earth. In order to create the optimally standardized bodies that cosmonauts would require, top secret military laboratories were set up in 1970s East Germany. The New Man the modern colonist of space was intensively trained for the purpose of surviving years of weightlessness in outer space. Experiments were carried out in prisons, hospitals and army barracks with the aim of creating the perfect body: self-sufficient and able to endure extreme conditions for as long as possible. In order to exert dominance over space, it was first necessary to exert total control over those who were being trained to conquer it. Ines Geipel unravels this largely unknown and extraordinary history by delving into East German military records and talking to those who bear the scars of this state-inflicted trauma. Some of the older scientists conducting experiments had already served under the Nazi regime; others threw themselves into collaborating with the Stasi via the military research programme in order to avoid dealing with the war s emotional legacy. Written like a thriller and infused with empathy from someone who had herself experienced the debilitating effects of state-administered doping programmes in the former GDR, this book exposes some of the most disturbing episodes in Germany s recent past.

Unknown soldier

Dual text. 26 April 2018. The day began like days that you can’t ever forget often do: normal, bright, sunny. In Berlin. A normal sky, normal coffee. I had to go into the city. A press conference was scheduled for 11 o’clock. On the podium three women. They were going to tell their stories. I was the moderator and was prepared accordingly.

Today is 26 April 2021. Exactly three years ago, something entered my life. That’s what people say looking back. I clearly remember standing at the front of the stage during the press conference. In the room were a large number of media representatives. To my right, the three women. At some point I stepped back two or three paces so that I could see them from behind. As if their backs would also speak, I thought. As if it were possible to be in front and behind at the same time. As if the two were distinct from one another. A kind of dual text. The women spoke of abuse and violence in sport. Calmly, clearly, forcefully. At least that’s what it must have sounded like in the room. They said what they had to say. The journalists asked their questions. It sounded like a completely normal press conference.

26 April 2021. I am sitting at the kitchen table and start writing this down. I think about a report. The first image is the backs, the second the e-mail I received twelve hours after the press conference. I have it in front of me. It says: ‘OK, sweetie, you’ve had your fun. Much too long, in our opinion. Now it’s our turn and it won’t be fun. No stone will be left unturned. You can bank on it. U.S.’

I sometimes get e-mails that start with ‘sweetie’. Hello, sweetie, or listen, sweetie, or hey, sweetie. I print them out and keep them in a special binder. As far as I’m concerned, they are eyewitness accounts. The sweetie mail of 26 April 2018 had the e-mail address unknownsoldier@ – and didn’t end up in the binder. It remained on my desk. Unknown soldier. It was evidently meant to sound important, some kind of secret mission. But what was to be made of it? Was someone trying to frighten me? And why? Wasn’t it going a bit far? When I think back to the situation today, I imagine Gerhard Richter’s cloudy pictures. Blurred, out of focus, without clear contours. But perhaps there’s no need for a picture. Perhaps I should just try to write down what happened.

The unknown soldier. It called to mind the grave of the unknown soldier in Canberra that I visited years ago. All the red flowers on the wall. They were poppies. Later I thought of camouflage dress, lowered visors, and my father. Almost fifteen years working for Department IV of the State Security, military training, spy, border crosser, West agent with eight different identities. He was the unknown soldier in my head. But was that necessary just because of another stupid e-mail? I hesitated. The thing with the East. It hadn’t got any easier over the years. Something had come back, shifted, moving in an endless loop. At least that’s how I felt. Twenty years ago it had seemed sorted, with dissertations, detailed research and investigation. But now it was as unsettled as ever. Slippery, vague, bottomless. More and more the East looked as if it were being questioned out of existence, rewritten, filtered out, reinterpreted.

If you ask people who know about it, they speak strangely of a Restoration, but they seem tired of it all. What remains of a country and a system that no longer exists? What was its core? What is its legacy if not just personal memories? And why unknown soldier? Who wanted to make their presence felt again? My gaze rested on the two letters U.S. Strange. More so, because the unknown soldier was evidently alluding to what had been occupying me for some time.

Pneumatic. I always have my Mac with me when I travel. That way I can reconstruct fairly well where and when I was in a particular institution, office or archive. According to the computer, in the week before 26 April 2018, I was in the military archive in Freiburg. I like going there. The days in that place are somehow pleasantly ritualized: the entrance door matt white, metal, matter-of-fact. The pneumatic sound, delicate, scraping. A cold suction noise as it closes. Click. I have to pass a checkpoint and them I’m inside.

That April three years ago was hot, the Freiburg reading room a refrigerator. I had socks with me. The files I wanted were on the checkout counter. The man who slid them towards me smiled kindly. I took the pile. Was that the beginning? There was a term I’d had in my head for some time: military-industrial complex, known in German as MIK. During the GDR days we had often joked about it. When we passed a Russian barracks, we said MIK. Whenever there was the silvery smell of radiation, we called it MIK. Restricted areas, black holes in the system – that was MIK. What did it mean? Who could we have asked?

Polytrauma. In 1989 MIK was gone. Disappeared, like so much else? But somehow MIK was stuck inside me and had a life of its own. Virtual Eye, the bionic brain GPS, Sea Hunter, the Mars cities planned by NASA – whenever I heard or read something to do with military and research, these three letters came into my mind like flashes of light. At some point I thought that whatever it was, it was material that was worth looking into. And also, how come we know so little about it? Or am I the only one who knows nothing about it? That’s why I decided to go to Freiburg. If there was anything to find out about MIK, that would be the place. I looked on the Internet and discovered that Freiburg was where everything to do with the GDR military research complex, or at least what was left of it, was kept. Documents on Bad Saarow Military Medical Academy and the Central Military Hospital, Königsbrück Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Stralsund Navy Medicine Institute, the Academy of Sciences, the Interkosmos programme. Holdings transferred to the Freiburg Military Archive from the Bundeswehrkommando Ost, which only existed from October 1990 to June 1991. MIK. Like investigating an imprecise memory, something that had always been there without ever being questioned. An obsolete fantasy, a relic of the Cold War, a conspiracy theory? Perhaps it had rather to do with what is inside us. With the bloodhound of history, which picks up the scent and trots off because that’s what it does, with its nose to the ground.

The air conditioning clanks. In front of me the files, the catalogue numbers. I look out of the window. Where am I? In April 2018. A bank of early summer clouds drifts gracefully past the archive window. I think of temptation, inertia, overview and distance. I’m sitting over fragile pieces of paper. Archives are strange places. In effect time capsules. Someone shuts out the here and now, draws you down a long corridor, hangs around for a while and then stops in front of something that happened in the past but hasn’t found its place. It’s still on its way, not yet landed.

On my order list for the archive week in April 2018: ‘clinical picture and treatment of selected sabotage poisons’, ‘consequences of ionizing radiation on tissue’, ‘new findings on panic in battle’, ‘placenta research’, ‘medical preparation of cosmonaut candidates’, ‘psychiatric aspects of suicide attempts by prisoners’, ‘blood substitutes’, ‘performance-oriented uses of women’, ‘polytrauma’.1 Items in the digital ordering system that caught my eye. But where to start? With sky. Definitely there. With the question of habitable zones and extraterrestrial life. With something that is bigger, older, more infinite than anything we can imagine. Isn’t there something that exists even without us?

Isolation chamber. ‘Human beings remain the most universal, flexible and important component of a control system, whereby an effectively coordinated distribution of functions between humans and machines improves the reliability of the overall system.’2 This is the first sentence of the postdoctoral thesis by Hans Haase, an aerospace medicine specialist born in 1937, from the Institute for Aerospace Medicine in Königsbrück, just a few kilometres from Dresden. The institute, a facility of the National People’s Army (NVA), was answerable to the Ministry of National Defence. Haase was its deputy director and sometime chair of the Cosmic Biology and Medicine working group3 within the Interkosmos programme. He also supervised Major General Sigmund Jähn, the first German in space, who orbited the Earth in summer 1978. Haase defended his cosmonaut thesis in November 1988. During the intervening ten years, not only in Königsbrück, there was a ‘systematic study of aerospace medicine projects’, as stated in the minutes of a meeting of the Leibniz Sozietät der Wissenschaften zu Berlin in 2008.4

A system within a system that was systematically researched. What was that about? Space travel is the ultimate heroic project, complete with smiling photos and a good portion of national pride. Perhaps it’s the rigid spacesuits, the anachronistic outfits, which have somehow always prevented me from taking all of the space exploration images seriously. Lots of waving from the capsule, floating gently in space, wide-legged hops on the moon. As if watching an ecstatic group of people fooling around in nowhere land, protected only by the universe. But...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Nick Somers |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Schlagworte | Aerospace • anti-doping activism • Astronaut • Astronaut training • books about the space race during war • communism in space • cosmonauts • Doping • German Democratic Republic • Health • how did the GDR exploit its citizens • how did the GDR participate in the space race • Interkosmos • man on the Moon • Olympic athlete • Sigmund Jähn • Soviet Union • space • space experiments • Space race • Sputnik • Surviving in space • USA • wartime space exploration • Weightlessness • what did the GDR do to train cosmonauts |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6000-9 / 1509560009 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6000-4 / 9781509560004 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 368 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich