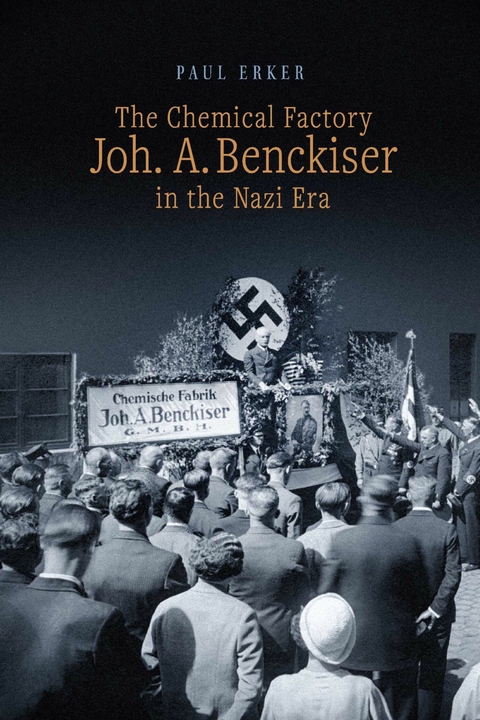

Introduction

Judgement has long since been passed by the general public on the Reimann family and the stance they took during the Nazi era. Dr. Albert Reimann Senior (*1868) and Dr. Albert Reimann Junior (*1896), managing directors and owners of the Chemische Werke J.A. Benckiser GmbH in Ludwigshafen, are considered fanatical antisemites and Nazi supporters who were deeply involved in the crimes of the National Socialist regime, especially in the mistreatment of forced labourers, as well as being active perpetrators themselves. Triggered by a sensation-seeking ‘tell-all’ article in the

Bild am Sonntag (

BamS) newspaper on 24 March 2019 and the subsequent scandalmongering in the world press and media coverage – which gained a dynamism of its own, pouncing on this story of a family that, up until then, had been highly discreet and far from the public eye – the two Reimanns were even portrayed by their own family as criminals who should have been imprisoned.

1 The accusations added up to a downright demonising of the two company owners, often without any distinction being made between the involvement, behaviour and deeds of either the father or the son, and with the abuse and assault perpetrated by third parties at the time being directly attributed to them personally.

2 “The two company patriarchs Albert Reimann Sr. and Albert Reimann Jr. inflicted violence and even abuse on forced labourers”, one newspaper stated.

3 The list of offences explicitly and implicitly attributed to the Reimanns is long. Talk is of ‘torture in the Reimann villa’ and ‘much abuse’ of forced labourers in the private residence;

4 as temporary president of the IHK – the Chamber of Commerce and Industry – (Reimann Sr.) and city councillor in Ludwigshafen (Reimann Jr.) they had actively supported the

Gleichschaltung (Nazification of state and society) and the seizure of power by the Nazis on a municipal level; the Reimanns also ensured the elimination and break-up of at least one Jewish rival company and had, therefore, ‘actively participated in the Aryanization, expropriation and annihilation of Jewish businesses’.

5 In addition, or so it is implied, the Reimanns virtually co-financed the Holocaust through their donations to the SS – an accusation that the Alfred Landecker Foundation, founded by the Reimann family as a result of allegations that had become known, even exacerbated to a large extent, despite the lack of justification or evidence. On the Foundation’s homepage under the heading ‘Why we exist’, mention is made of payments by the Reimanns to the armed combat

Waffen-SS.

6 Not even the

Bild am Sonntag made such claims. On top of all this, there are further accusations: the company was not only conspicuous for its ‘use of a particularly large number of forced labourers’ but was also a place of ‘physical and sexual abuse of women brought in to work as slaves from Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe’.

7 It was considered particularly perfidious that Albert Reimann Jr., as a fanatical antisemite, apparently had an extramarital affair with a young ‘half-Jewish’ woman in his company at the same time.

8Much of this is incorrect or exaggerated, either from a purely factual standpoint or in the moral severity of its assessment, and the apparent singularity of the Reimanns’ wrongdoings and entanglement, as entrepreneurs, in Nazi crimes and with the Nazi regime quickly dissipates when compared with other family company owners such as Rudolf-August Oetker, Günther Quandt, Carl Freudenberg, Fritz and Horst Sartorius, Karl Merck, Ernst Boehringer and Karl Schmitz-Scholl Jr. (Tengelmann). Nevertheless, evidence does indeed exist in a number of different sources with regard to many of the moral and personal shortcomings of the two Reimanns and their guilt and involvement in Nazi injustice and crimes, as the present investigation shows. It is not, however, a question of assessing the degree of their active participation or knowledge, acceptance or tolerance, or even the deliberate furthering of abuse in a legal sense. In a small Mittelstand company with a few hundred employees, such as the Chemische Fabrik Joh. A. Benckiser GmbH was at that time, nothing remained hidden. As a consequence, the two company owners bear responsibility for sexual abuse, excesses violence and denunciation in their company as well as for the guilt they brought upon themselves.

For historians, such a past history does not make the task any easier, as they could readily be suspected themselves of exculpation resulting from the differentiated, contextualised and comparative evaluation of sources and investigative analyses. And all the more so, since this study appears at a time when, despite the wealth of scholarly research on National Socialism, strict moral standards are increasingly being applied to the evaluation of an individual’s actions between 1933 and 1945. On top of this, the historical interpretation of the Nazi era has “to a large extent [been] permeated, almost conquered, by the language of the accusers and moralisers”, as the British historian Richard J. Evans laments.

9 However, backward-looking moral indignation is of no explanatory value whatsoever

10 and a critical, source-related analysis of the past in all its complexity must, therefore, be presented to counteract these trends, more than ever before.

Quite apart from this, in the case of the Reimanns, there was really nothing new to ‘tell’ since it has long been possible to gain information on conditions at the Joh. A. Benckiser chemical factory during the Nazi era, and especially the use of forced labourers, from a number of different publications. In 2004, Eginhard Scharf published a detailed study on foreign forced labourers in Ludwigshafen am Rhein between 1939 and 1945 and, as far back as 1978, the

Benckiser-Chronik II provided a detailed account of the company’s history during the Nazi era that would have provided the basis for a critical analysis.

11Neither the public nor, to an even lesser extent, the family and the ‘core company’ at the time – that had, meanwhile, been profoundly transformed – had any interest, however, in a critical analysis of the past. It was not until the trend to examine the role of family businesses during the Nazi era from a corporate historical and academic perspective, precipitated by the scandalous reports in the media on the history of the Quandt family and the questions asked in public about the ‘how and why’ behind the fortune of one of Germany’s richest entrepreneurial families, that sensibilities and interests slowly changed – both among the public and (at least some of) the families concerned. In the meantime numerous studies on family businesses, ranging from Quandt and Freudenberg, Oetker, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Merck, to Sartorius and Tengelmann, have been published on the basis of material in company and family archives made accessible for this purpose.

12In July 2016 and, therefore, long before the scandalisation in the media, the author of this work was commissioned by the Reimann family and the JAB Holding Company to conduct an independent academic study on the history of the company and its then owners in the Nazi era. In January 2019 an interim report was presented to the family in Vienna. As such, they had been informed about the wrongdoings of and accusations against their father, Reimann Jr., and their grandfather, Reimann Sr., long before the

BamS article was published.

The central focus of the study is initially on the two entrepreneurial personalities and their attitudes and behaviour within the company and in public. To what extent did Joh. A. Benckiser become a ‘Nazi model company’, what corresponding form did this take in corporate culture and how were the National Socialist principles of Betriebsführerschaft (factory leadership) and Betriebsgemeinschaft (factory community) implemented? How did the company act towards Nazi officials and armaments authorities and to what extent did the Nazi economic policy and the war period open up opportunities and options that could change the established situation among competitors on the German domestic market – and consequently on a European level – to its own advantage? Over and above this dual biographical approach, however, the company itself and the specific branch and respective business sectors also have to be examined more closely. The Chemische Fabrik Joh. A. Benckiser, like many other family-owned companies that only later developed into large international corporations, was a small Mittelstand enterprise at that time, albeit with a notable tradition having been founded in 1823, and a highly chequered history marked by ups and downs, employing a mere 200 people, of which a handful were executive staff members. From 1939 onwards these also included Albert Reimann Jr.’s brother-in-law, Hans Dubbers, as head of the personnel and business administration departments. The circle of family members involved had, therefore, been expanded to include the brother-in-law as well as Albert Reimann’s sister, Else Dubbers, née Reimann, to whom he remained close throughout his life, culminating in the adoption of her four children at the end of the...