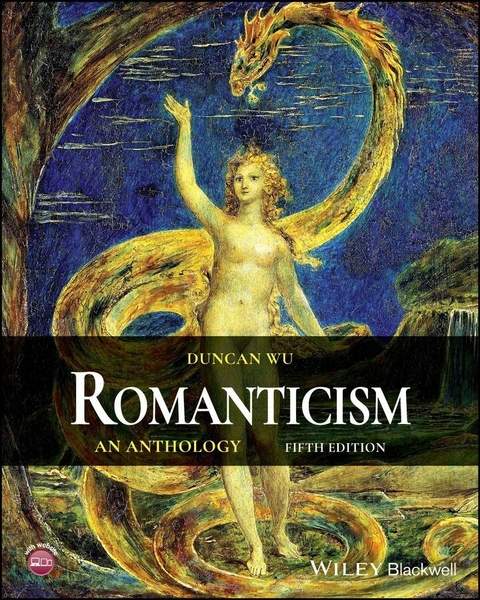

Romanticism (eBook)

1710 Seiten

Wiley-Blackwell (Verlag)

978-1-394-21087-9 (ISBN)

The essential work on Romanticism, revised and condensed for student convenience

Standing as the essential work on Romanticism, Duncan Wu's Romanticism: An Anthology has been appreciated by thousands of literature students and their teachers across the globe since its first appearance in 1994. This Fifth Edition has been revised to reduce the size of the book and the burden of carrying it around a university campus. It includes the six canonical authors: Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Byron, and Shelley. The Fourth Edition of the anthology, with complete and uncut texts of a wealth of Romantic authors, is available to all readers of the Fifth Edition via online access.

Authors are introduced successively by their dates of birth; works are placed in order of composition where known and, when not known, by date of publication. Except for works in dialect or in which archaic effects were deliberately sought, punctuation and orthography are normalized, pervasive initial capitals and italics removed, and contractions expanded except where they are of metrical significance. Texts are edited for this volume from both manuscript and early printed sources.

Romanticism: An Anthology contains everything a teacher needs for full coverage of the canonical poets, with illustrations and a chronological timeline to provide readers with important historical context.

Duncan Wu is Raymond A. Wagner Professor of English Literature at Georgetown University, Washington DC. He was also Professor of English Literature at Glasgow University and Professor of English Language and Literature at St Catherine's College, Oxford. He is the author of numerous books on the Romantics and poetry.

Introduction

I perceive that in Germany as well as in Italy there is a great struggle about what they call Classical and Romantic, terms which were not subjects of Classification in England – at least when I left it four or five years ago.

(Byron, in the rejected Dedication to Marino Faliero, 14 August 1820)

When Lyrical Ballads first appeared in 1798 the word ‘Romantic’ was no compliment. It meant ‘fanciful’, ‘light’, even ‘inconsequential’. Wordsworth and Coleridge would have resisted its application; twenty years later, the new generation of writers would recognize it as the counter in a debate conducted by European intellectuals, barely relevant to what they were doing. Perhaps that is the nature of academic discourse: even when conducted by practitioners, it may not bear greatly on the creative process, which has its own customs and rules which vary between writers.

Originally a descriptive term, ‘Romance’ used to refer to the verse epics of Tasso and Ariosto. Eighteenth‐century critics like Thomas Warton used it in relation to fiction, often European, and in that context Novalis applied it to German literature. The idea didn’t take flight until August Wilhelm Schlegel used it in a lecture course at Berlin, 1801–4, when he made the distinction mentioned by Byron. Romantic literature, he argued, appeared in the Middle Ages with the work of Dante, Petrarchis and Boccaccio; in reaction to Classicism it was identified with progressive and Christian views. In another course of lectures in Vienna, 1808–9, he went further: Romanticism was ‘organic’ and ‘plastic’, as against the ‘mechanical’ tendencies of Classicism. By 1821, when Byron dedicated Marino Faliero to Goethe, the debate was in full flood: Schlegel’s ideas had been picked up and extrapolated by Madame de Staël, and in 1818 Stendhal became the first Frenchman to claim himself un romantique – for Shakespeare and against Racine; for Byron and against Boileau. Within a year Spanish and Portuguese critics too were wading in.

Having originated in disagreement, and largely in the academe, the concept has remained fluid ever since, and though many definitions are suggested, none commands universal agreement. In that respect Romanticism is distinct from movements formed by artists, which tend to be more coherent in their ambitions, at least to begin with. When the Pre‐Raphaelite Brotherhood turned themselves into a school, they wanted to challenge received notions about pictorial representation; the Imagists published a manifesto of sorts in Blast that presented an agreed line of attack. The British Romantic poets could not have done this. Blake, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley and Keats never all met in the same room and, had they done so, would have quarrelled.

One factor was the generation gap. Byron, Shelley and Keats might have enjoyed the company of Wordsworth as he was in his later twenties and early thirties, but by the time they reached artistic maturity – c.1816 for Shelley and Byron, 1819 for Keats – he was well into middle age, had accepted the job of Distributor of Stamps for Westmorland, and appeared to have forsaken the religious and political views of his youth. His support for the Tory Lord Lonsdale in the 1818 general election confirmed his association with a brand of conservatism they loathed. So far as they were concerned, he had betrayed the promise of ‘Tintern Abbey’ for a sinecure. All this makes it doubly unfortunate they could not read ‘The Prelude’, unpublished until 1850, by which time they were dead. Had they done so, they would have seen him differently.

Byron caught up with the critical debate surrounding Romanticism in 1821, but Coleridge beat him to it by a year. In 1820 the sage of Highgate compiled a list of ‘Romantic’ writers in which the only English poets of the day were Southey, Scott and Byron. Byron would have disliked being placed in the same class as Southey, whom he hated. But this only goes to show how resistant the concept is to codification – or at least to a form of codification that makes any sense. Perhaps the best advice one can offer is to be suspicious of anyone who claims to have the answer.

Romanticism: Culture and Society

The Romantic period has an immediacy earlier ones tend to lack. This is because so many of our values and preoccupations derive from it. It coincides with the moment at which Britain became an industrial economy. Factories sprang up in towns and cities across the country, and the agrarian lives people had known for centuries stopped being taken for granted. Instead, labourers moved from the country into large conurbations, working long hours in close proximity to each other. This had a number of consequences, not least that they began to fight for their ‘rights’. Today we take our rights for granted, forgetting the intellectual journey working people had to make merely to understand they had such things. For many, something very similar to the feudal system of medieval times continued to dictate their place in society – though things were changing.

The process by which people were awakened to a sense of self‐determination was global. It began with the American Revolution and continued with that in France. And the impact of those upheavals cannot be overstated. Whole populations began to question the legitimacy of hereditary monarchs whose right to rule had once been accepted without question. It was not surprising that struggles elsewhere to do away with monarchical government affected the British; in fact, the real surprise is their refusal to take the same step – a testament to the determination with which their government stifled unrest. By the summer of 1817, it had in place a sophisticated network of spies practised in thwarting popular uprisings in Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. A favoured technique was for agents provocateurs to incite revolutionary activity, and for the government to execute supporters.

Revolution in America and France generated conflict because of the effect on international trade. By the time Wordsworth was in his mid‐twenties, Britain was embroiled in nothing less than world war which, unlike those in the twentieth century, would last not for years but decades. From 1793 to 1802, and then from 1803 until 1815, Britain grappled with France across the globe, often fighting single‐handedly against a well‐equipped and resourceful enemy who, for much of that time, had the advantage. On an island‐bound people like the British, the constant threat of invasion over more than two decades had a powerful effect. Whatever one’s sympathies with the ideals of the American and French Revolutions, it became difficult to express anything but support for the national cause. Patriotic feeling in its most jingoistic form ran high, something vividly indicated by the caricatures of James Gillray.

Then as now, the cost of war was exorbitant and, in order to pay its debts, the post‐war government of Lord Liverpool had to levy higher taxes. On 14 June 1815, additional expenditure arising from Napoleon’s escape from Elba and its consequences led Nicholas Vansittart, Chancellor of the Exchequer, to raise £79 million through tax revenues. On 18 March 1816, the government decided to repeal income tax altogether, causing the burden disproportionately to fall upon the poor, in the form of duties on tobacco, beer, sugar and tea. This generated intense hardship at a time when jobs were scarce and pay low.

International conflict, the threat of invasion by Napoleon, social and political discontent – the writers in this book lived with these things, and were shaped by them. To that extent, it is appropriate to consider them as war poets, surrounded by upheaval and conflict, and passionately engaged with it. That engagement was made possible by another important development: the rise of the media.

This period was the first in history in which the population could keep abreast of political developments through newsprint. Historians have long acknowledged that the French press played an important part in the Revolution, enjoying unprecedented freedom between the fall of the Bastille in July 1789 and that of the monarchy in August 1792. It was not for nothing that J. L. Carra and Antoine‐Joseph Gorsas, both journalists, were among those guillotined by Robespierre. The inventions of the steam‐press (by which The Times was produced from 1814 onwards) and the paper‐making machine (in 1803) meant it was easier than ever to produce newspapers on an industrial scale. And from around 1810 the mail‐coach, which travelled at the hitherto unimaginable speed of 12 miles an hour, enabled publishers to distribute on a nationwide scale. For the first time, it was possible for Coleridge in Keswick to receive the papers the day after publication before sending them on to Wordsworth in Grasmere; there is no sense in which those living in the provinces were cut off from world affairs.

Nor was it only poets in the Lake District who kept up with the news: bulletins were now available to the poor and illiterate. Cobbett sold his Political Register at a price that made it accessible to the labouring folk he addressed – twopence, which led Tory critics to christen it ‘twopenny trash’. Groups of men would club together and buy a single copy, which would be read aloud.

The new‐found...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik |

| Schlagworte | 19th century literature • Anna Laetitia Barbauld • Blake • Byron • Charles Lamb • Coleridge • Dorothy Wordsworth • English literature • Helen Maria Williams • John Thelwall • Keats • Mary Robinson • Robert Southey • Romantic authors • Romanticism • Shelley • Thomas de Quincey • William Hazlitt • Wordsworth |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-21087-6 / 1394210876 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-21087-9 / 9781394210879 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,4 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich