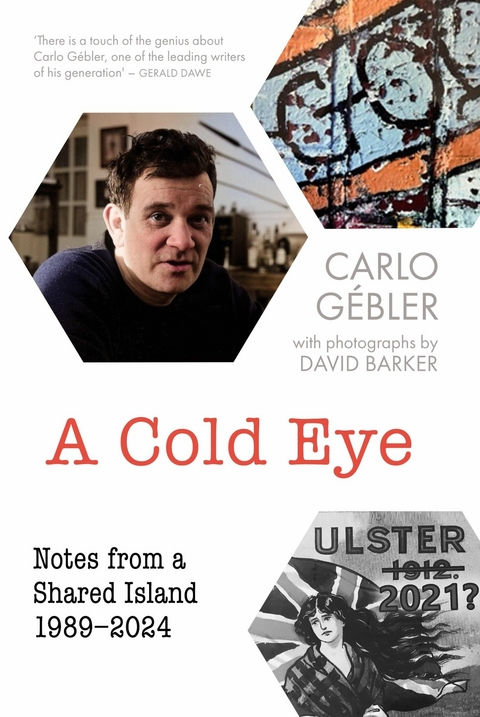

A Cold Eye (eBook)

304 Seiten

New Island Books (Verlag)

978-1-84840-901-9 (ISBN)

CARLO Gxc3x89BLER is a novelist, biographer, playwright, memoirist, critic and occasional broadcaster. He has worked as a prison and university teacher for many years and also worked with Patrick Maguire, who was wrongly convicted ofxc2xa0the IRA Guildford pub bombings, on his memoir My Fatherxe2x80x99s Watch. He is a member of Aosdxc3xa1na and lives in Enniskillen,xc2xa0Northern Ireland.

CARLO Gxc3x89BLER is a novelist, biographer, playwright, memoirist, critic and occasional broadcaster. He has worked as a prison and university teacher for many years and also worked with Patrick Maguire, who was wrongly convicted ofxc2xa0the IRA Guildford pub bombings, on his memoir My Fatherxe2x80x99s Watch. He is a member of Aosdxc3xa1na and lives in Enniskillen,xc2xa0Northern Ireland.

The Fall of Communism, the End of History (Not) (Friday, 10 November 1989)

I drove to Belfast with the radio on, BBC Radio 4. The morning news was almost entirely about the Iron Curtain and its often predicted, yet still somehow, now it’s happening, unbelievable collapse.

Yesterday, Thursday, the East Berlin party chief, Günter Schabowski, held a press conference and said that, starting at midnight, East Germans would be free to leave the country at any point along the border, including the crossing points through the wall in Berlin. This morning, as I learnt from listening to Today with Peter Hobday and Sue MacGregor while driving through the murk (some rain, some wind, an Irish autumn day, predictable and hackneyed, the kind that required only intermittent use of the wipers), East German bulldozers had opened and were opening new crossing points to allow East Berliners to go west. A comment on the events unfolding in Germany was sought, of course, from our beloved prime minister, Mrs Thatcher, and in her perplexing, caressing and, according to many, seductive voice (entirely the creation of a speech coach: her real register, like her nature, is spiky and shrill), the PM spoke of what was happening in Germany as ‘a great day for freedom’. A great day for freedom! Well, yeah, technically it’s true – East Germans are free to go west – but linguistically the comment was pure dreck, utterly banal. Why can’t politicians go for newly minted language? But no, they won’t.

Sometime after nine (Desert Island Discs on the radio; Sue Lawley’s guest was Ian Botham: stodgy, charmless, crass – a philistine mediocrity) I got to West Belfast (damp streets, grey sky, to my left the mountains in the distance, dark and brooding) and things were flowing nicely. And then they were not flowing nicely any more, and I had to stop. In front of me, a mechanical diplodocus straddled the road, and from its long neck there dangled a heavy metal sheath (actually bombproof cladding) that was going to be first lifted, then flown, and finally dropped onto the internal brick structure of a section of the ‘peace line’ that ran beside the road, one of dozens of similar barriers that have been constructed since the start of the Troubles to keep antagonistic communities apart in Northern Ireland.

I turned off the engine and looked at the dashboard clock. I was on my way to meet a psychiatrist to discuss the psychological effects of the Troubles. I’d always assumed the violence must raise the levels of anxiety and depression. But I was wrong. Psychological well-being in Northern Ireland (measured in terms of suicides, para suicides, prescriptions for sleeping tablets and so on) was about the same as anywhere else in the United Kingdom, and the psychiatrist who was going to enlighten me further about this counter-intuitive fact was, at that moment, as I sat waiting for the peace line to be reinforced, sitting in his room in the hospital, having agreed, despite his incredibly busy schedule, to talk to me. Only now it looked as if I was going to be late, in which case I’d probably miss my slot and miss having what I was sure was going to be a fascinating conversation that would hugely enhance the book I had come to Northern Ireland to write; and if I wanted another shot, I’d have to arrange a new time, which would mean a second 180-mile journey from Enniskillen to West Belfast and back again. What a drag. Why couldn’t it have been a different day, a different hour, when this bit of the peace line was slated for augmentation? I was a writer writing a book with a delivery date, for Christ’ssake, and I shouldn’t be held up like this in the street as I made my way to my very important appointment.

In another part of the brain, a separate compartment from the place where I fret about my timetable – this is a place of perennial anxiety: I hate to be late – a completely different set of thoughts was in play. In Germany over the last few months, crowds regularly gathered on both sides of the Berlin Wall to shout ‘Democracy, now or never!’ and ‘Free passage for free citizens!’ but in Belfast and elsewherein Northern Ireland, as far as I was aware, the peace lines had been wanted and welcomed, and no crowds had ever gathered and asked for them to be torn down. And as I’d heard earlier on the radio, at that very moment, while I was watching one kind of wall being improved and strengthened in Belfast, the wall in Berlin was being bulldozed. Here was an opportunity for a compare-and-contrast riff – Germany and Europe: forwards; Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom: backwards – and therefore, I thought, I should observe, record to memory what was happening, and later I could use this material in the book I was writing. I could see this made sense, and so I tried. I looked around. What did I see?

A man sauntered past. He carried a couple of SPAR plastic bags. Through the thin plastic I thought I could make out bread, milk, sausages and tins of something, perhaps rice pudding. A dog, a heavy old Labrador, waddled by. I noticed a coupleof old ladies with wheeled shopping baskets, both in coats and hats and scarves and gloves (they were so well insulated they were almost like walking duvets).

Finally, I noticed the downstairs window of a terraced house across the road from the peace line, the lace curtain opening a crack and an old female face peering out at the unfolding scene, in just the same way, I imagined, as she might have looked at a neighbour who was drunk and staggering, oracouple who should definitely not be courting walking arm in arm.Behind and ahead, a sense of traffic piling up; the tinny sound of music on the radios of some of the waiting cars mingled with the heavier mechanical sounds of the crane, its diesel engine churning, its taut cabling running over wheels and pinging, the lifting system harrumphing like breath and the sheath clattering, swinging and banging as it was dropped carefully and very slowly over the brick support and lowered towards the ground. It was like being in the theatre and seeing a flat being flown in during a scene change. And then the change was done. The chains were detached. With further harrumphing, the diplodocus crawled away. I turned on my engine. Botham came back. The traffic started to move. I was on my way.

I was late for my appointment but the psychiatrist, when I explained, was blithe and understanding. It was Belfast, West Belfast, and one was always being held up, he said – by checkpoints, or bombs, or because they were working on the peace line. That’s how it went. He didn’t mindmy being latein the slightestand he had time to spare. I sat in his small office and we talked, and when we were done he gathered some academic papers by psychiatrists for me to take away and read.

I left and retraced my route. I passed the peace line I’d seen earlier with its new cladding. No sign of the diplodocus. I drove home, and when I walked into the kitchen in our flat I found my oldest daughter back from school (she was at the table in her school uniform: her uniform is blue and worn with a sash; she has started at the Integrated School in Enniskillen) along with my wife and two sons. I was asked what sort of day I had had. Interesting, I said. I’d had to stop, I said, and watch a crane drop a huge piece of metal casing onto a section of a peace line in West Belfast, while hundreds of miles to the east a border was being demolished, a moment of synchronicity out of which I might be able to wring some interesting copy.

What was Checkpoint Charlie, asked my oldest daughter. She’d overheard the words on the news and didn’t know what they meant. As onions for the tomato sauce were chopped and gently fried, and as the water for the pasta was heated on the stove, I did my best to explain. In Berlin in the 1960s, I said, a wall had been built down the middle of the city and Checkpoint Charlie was one of the crossing points in that wall where people could go from one side to the other, from east to west and vice versa; at the same time, it was also a symbol of the Cold War. My knowledge, I realised as I burbled on, was vacuous and shallow, being mostly derived from photographs I’d seen in newspapers and on television of the Berlin Wall and the fearsome German Democratic Republic guards who guarded it, articles I’d read about hairy escapes via tunnels under the wall and spy films about the Cold War, particularly the film of John le Carré’s novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, which I’d loved (with Richard Burton as Alec Leamas: weary, cynical, noble, incredible). My ignorance was staggering, but mercifully went unnoticed.

*

A few days after my Belfast trip and my meeting with the diplodocus, I met a local journalist in Enniskillen who told me how he’d recently gone to watch a small road between Fermanagh and Cavan being blocked with dragon’s teeth to stop the IRA using it, although everyone else would also be stopped from using it. There were Garda Síochána and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) policemen present; they all knew one another and they all chatted happily as the army engineers got the blocks in place. The policemen’s conversations were about how in Germany the wall had fallen, but in Ireland it was the same old, same old. Some of us in Ireland, the police postulated, might want a new future, but most of us preferred to say ‘To hell with the future, let’s get on with the past …’ and so we just went on doing what we had always done;...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Briefe / Tagebücher | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Carlo Gebler • Diary • edna o'brien • Ireland • Northern Ireland • personal history • shared island • The Troubles • Troubles |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84840-901-X / 184840901X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84840-901-9 / 9781848409019 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich