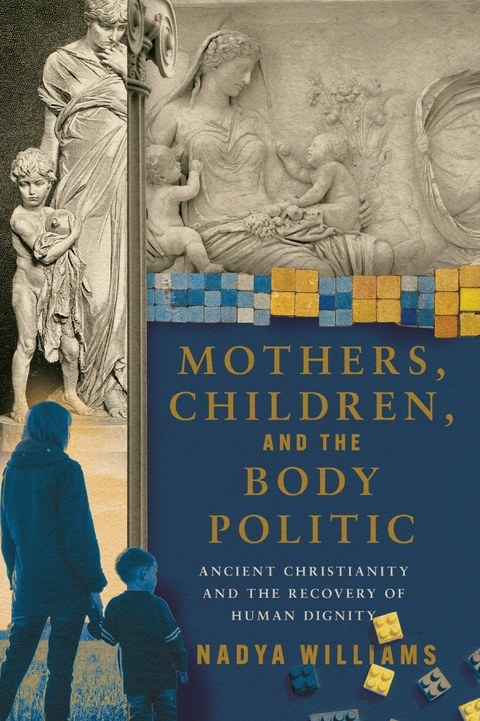

Mothers, Children, and the Body Politic (eBook)

240 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0913-0 (ISBN)

Nadya Williams (PhD, Princeton) walked away from academia after fifteen years as a professor of history and classics. She is now a homeschool mom, book review editor at Current, and a contributing editor at Providence magazine. She is the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023), and numerous articles and essays in Current, Plough, Christianity Today, Front Porch Republic, Fairer Disputations, Law and Liberty, Church Life Journal, and others. She and her husband, Dan, are parents to one adult son and two children still at home. They live and homeschool in Ashland, a small town near Cleveland, Ohio.

Nadya Williams (PhD, Princeton) walked away from academia after fifteen years as a professor of history and classics. She is now a homeschool mom, book review editor at Current, and a contributing editor at Providence magazine. She is the author of Cultural Christians in the Early Church (Zondervan Academic, 2023), and numerous articles and essays in Current, Plough, Christianity Today, Front Porch Republic, Fairer Disputations, Law and Liberty, Church Life Journal, and others. She and her husband, Dan, are parents to one adult son and two children still at home. They live and homeschool in Ashland, a small town near Cleveland, Ohio.

Introduction

IN JULY 2023, I walked away from academia and tenure after fifteen years as a professor. This decision in and of itself was not so unusual. It is the twenty-first century, and plenty of people change careers, after all—especially in this post-2020 age of the Great Resignation. What shocked both friends and strangers alike, however, was what I decided to do instead. Instead of opting for the more typical alternative career choice for ex-academics, such as a consultant or UX researcher, I decided to stay at home full time (aside from some freelance writing and editing) to homeschool my children. “What a loss to the profession,” several friends and former colleagues commented. A couple of friends made tradwife jokes, all in good humor, about my becoming a stereotypical housewife. For what better image to evoke as the exact opposite of a serious academic professional, that stereotypical disheveled creature of crumpled tweed, elbow patches, and eyes perennially red from grading far too late into the night, powered by an excess of caffeine and peanut butter consumed straight out of the jar. With a spoon.

For the record, while everything else applies, unlike most male colleagues, I never did own a tweed jacket with elbow patches. Yet I am no tradwife frolicking in flower fields in a sundress and milking cows for cameras, rest assured. For one thing, sundresses are really not practical for either hanging out at flower fields or milking cows, I hear. But aside from the tradwife social media cosplays, too many married women today, evangelical and secular alike, have generally internalized the message that feminist writer and cultural icon Betty Friedan first articulated in her 1963 bestselling book The Feminine Mystique—even if they have never read Friedan or even heard of her.1 Friedan was a writer and journalist who was fired from her job for pregnancy, back when this was normal. She saw her contemporary stay-at-home moms (and, of course, herself) as bored, oppressed, and depressed. In response, she wrote her book as a manifesto for miserable modern married women’s liberation.2 (She had hoped that her therapist would cowrite the book with her. Alas, he turned down this irresistible offer.)3 An educated woman, in Friedan’s view, could never be truly fulfilled or happy if her life sphere were restricted to the domestic life. But what does such a view suggest about the value of motherhood and its essential companions—children?

DEVALUING CHILDREN AND MOTHERHOOD

Fast-forward sixty years. In August 2022, Bloomberg broke a sensationalizing news story, confidently asserting that “women not having kids get richer than men.”4 There it was, set forth already in the title of the article, a bold economic argument that put a price on human relationships and human life, leaping far beyond what Friedan, who was no absolute enemy of marriage and motherhood, had originally advocated. Marriage, the article aimed to show, cost something to women. And, of course, so did having children. In other words, if you are a woman and your chief aim is building up wealth and personal security (as the article presumes it surely should be), then your best course of action is clear. First, do not have children, and second, maybe marriage is not a good idea either. Here is an argument for a life of singlehood (albeit presumably not celibacy), and one that conflates economic wealth and career success with that more elusive and less easily measurable goal—flourishing.

I read this article a few months before I had finalized my decision to walk away from academia, but I did read it as a married mother of three children. To be honest, it made me angry. The argument boldly put on trial women like me—married and mothers—and found our lives and choices lacking. To be clear, it did not affect my joy in my family, but it was upsetting to learn that the article’s author might look at women like me with pity mingled with outright hyper-Friedanian disdain. I can only imagine what she would have said about my career change.

Before I go on to address responses to this article by experts, I must acknowledge an important point. There is often a perception in evangelical circles that church life is rigged to include and support mothers and exclude single women, making them feel lacking in much the same way as the Bloomberg article did for me. There is certainly some truth to this perception—although the precise degree varies depending on the specific congregation, theological tradition, location, and so on. There is no denying that single women experience significant challenges, and the church should do more to support their flourishing.5 And yet, there is also no denying that our surrounding culture is increasingly more hostile to motherhood and family.6 The cultural hostility to one group of women, in other words, in no way negates the existence of similarly intense hostility to another group. This brings us back to the Bloomberg article and the obvious question: Is this true? Are childless women really wealthier and happier than mothers?

Critics swiftly debunked the article’s false premises and misleading methodology, which did not include any married women in the study. Compelling data exists, in fact, that it is married women with children who are the best off economically of all categories of women in modern American society.7 Study after study shows that while single unwed mothers are not flourishing economically, people in happy marriages are financially better off, happier, and healthier.8 The happiness and health effects seem especially noticeable for men, who live longer if in a happy marriage, but women benefit too—in terms of both finances and health.9 Indeed, Brad Wilcox, who directs the National Marriage Project, has echoed Pope Francis in describing marriage as “a matter of social justice.”10

The veracity or falsehood of the Bloomberg article’s arguments, however, is less important than the mere fact of its existence and subsequent popularity. The very attempt in this work to propose the argument that it makes, and to do it so boldly, is a symptom of a pervasive problem in American society: the problem of devaluing motherhood and children in every sphere of modern life. That is the problem that I seek to confront in all its ugliness in the present book, with the conviction that it is impossible to address a problem whose existence and full repercussions in our world and our own lives we do not recognize or acknowledge openly. It is a problem that is symptomatic of a larger devaluing of human life in our society more generally.

The choice of someone to conduct “research” and write the piece, not to mention the willingness of a prominent media corporation such as Bloomberg to publish it, shows a desire in our society, one that is hidden in plain sight, to devalue motherhood and children by pricing human life. In any attempts to make such pricing happen overtly and in distinctly economic terms, the value of mothers (the ones who produce children) and children (the products that mothers nurture at various costs—first and foremost to themselves) invariably seems to come up short. Even if the main claim of the article is faulty, there are real costs attached to children and motherhood—costs that Anna Louie Sussman has declared have led to “The End of Babies.”11

First, the health-care costs associated with pregnancy and childbirth alone are staggering—even for a perfectly healthy pregnancy and delivery. As one recent study notes, “Women who give birth incur almost $19,000 in additional health costs and pay about $3,000 more out-of-pocket than women of the same age who do not give birth.”12 Then there is the cost of work hours lost to the employer, if a working mother takes leave according to the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), and the cost of wages lost to the employee. If the child has any disabilities that require assistance in school or later in life, then there is further economic cost to both the parents and society. In addition, the costs for disaster situations, such as those that require children to be placed in the foster-care system, require yet more financial resources from the state.

Numbers, one could say, do not lie. Children in this day and age are expensive, which means that motherhood is as well. This makes both children and motherhood luxury goods by economic default. It seems callous and crass to speak of motherhood and children in terms of plain economics, even as this has been the implied reality since the original legalization of abortion in 1973. The legal right to abortion made having children an economic choice, and the reversal of Roe v. Wade has not reversed this deeply embedded societal belief. Arguments for abortion as a necessary measure of poverty relief continue unabated.

At the same time, we know instinctively deep down—or, at least, we should know it, if we reflect—that this is not how it is meant to be. This is not how God looks at any of us—in his eyes, every single image bearer is priceless. Nevertheless, so often in our society, we conduct this kind of pricing of human “goods” without even thinking. The deadly storm over the past two years of the converging trifecta of the Covid-19 pandemic, reactions to the repeal of Roe, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, to mention just some relevant examples, has brought such conversations and questions to the fore more openly than before.

What is a human life worth? Are some lives more economically beneficial to society than others?...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum |

| Schlagworte | Body • Childbearing • child rearing • children • Civilians • Classical Antiquity • Classics Studies • commodification • devalue • Early • Early Christianity • Early Church • Faith • Family • Gender • Gender and Family • God • Gospel • Greco-Roman • Greco-roman Christianity • Greco-roman church • History • History of the Family • Humanity • Imago Dei • maternal • Mediterranean • Motherhood • Peace • Pregnancy • Pro-life • Redemption • war • Women • women and children |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0913-7 / 1514009137 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0913-0 / 9781514009130 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich