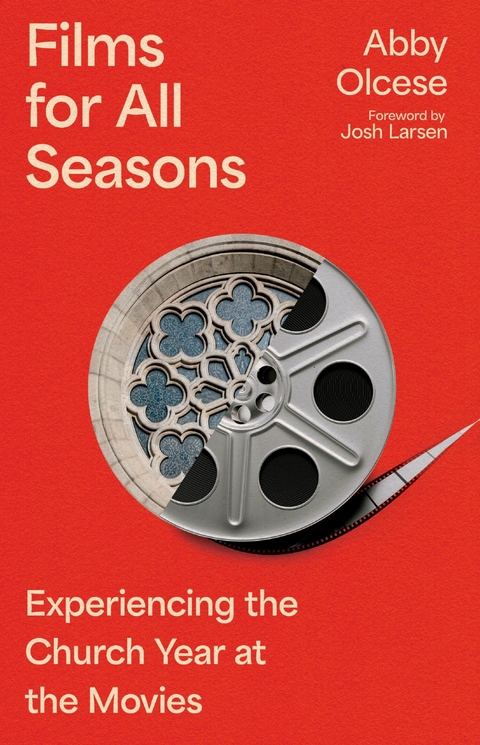

Films for All Seasons (eBook)

240 Seiten

IVP (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0785-3 (ISBN)

Abby Olcese is a writer on film, popular culture, and faith. Her work has appeared at Think Christian, Sojourners, Paste, RogerEbert.com, and /Film. She is also the film editor for The Pitch, a website and magazine serving the greater Kansas City, Missouri, area. She lives in Kansas City.

Abby Olcese is a writer on film, popular culture, and faith. Her work has appeared at Think Christian, Sojourners, Paste, RogerEbert.com, and /Film. She is also the film editor for The Pitch, a website and magazine serving the greater Kansas City, Missouri, area. She lives in Kansas City.

INTRODUCTION

Why Watch Films as a Spiritual Practice?

Stories rule our lives. We use narrative to make sense of where we come from, the kinds of people we want to be, and the relationships and experiences that have brought us to this point. When we make plans, we tell a story about what we think will happen. When we lie down at night and think back on what we did that day, we tell a story based on our memories. Stories stoke our curiosity, help us make sense of the world, and help us understand ourselves and others.

Our lives are also ruled by routines and rhythms, whether it’s a schedule we plan ourselves or the natural rhythms of sleep, work, play, social engagement, or worship that dictate our week. At least in the western world, that rhythm is a strange, potent mix of the religious and the secular. Each week contains days for work and days for rest based on the creation of the world in Genesis and the existence of the Sabbath. We observe the changing of the seasons with holidays and events that pull from natural patterns as well as biblical tradition.

If we think of our life as a story, seasons are how we mark the chapters. Each one contains distinct themes, whether it’s spring, summer, fall, and winter, or the seasons of infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and old age.

In the life of the church, those chapters are marked by the liturgical calendar, the annual cycle that takes us on a narrative journey through the Bible. As with any good story, we get to know a set of characters, and follow them as they learn, grow, encounter joys and sorrows, die, and in the case of Jesus, resurrect. We’re also constantly thinking about the ways this long story, made up of many stories, applies to the lives we lead now.1

The writer Dorothy Sayers recognized the inherent drama of this process in her 1938 essay The Greatest Drama Ever Staged, in which she wrote of the role of storytelling in church tradition: “The Christian faith is the most exciting drama that ever staggered the imagination of man—and the dogma is the drama.”2 The Bible tells an incredible story that weaves individual accounts of prophets, believers, disciples, the Son of God, and the early church into a grand arc showing how followers of God have tried, sometimes succeeded, and more often failed, to follow God’s divine teachings, finally receiving ultimate salvation in the form of Jesus Christ.

The individual stories of the Bible contain lessons teaching us how to live well as Christians. They also communicate broader themes about the nature of God’s love, how we’re called to respond to it, the deeply human ways we often fall short of that calling, and the transcendent times when we manage to meet it. These themes link the entire book together and become especially apparent during church holidays, when we specifically engage with the most powerful biblical narratives and the legacy of the church beyond them.

Stories and the Church Year

Depending on the tradition you come from, your knowledge of the cycle of life in the church may be detailed or it may be limited to major holidays such as Christmas or Easter. I grew up attending churches that didn’t spend much time on smaller holidays such as Pentecost or All Saints’ Day. As an adult, I became involved in the Episcopal Church, which emphasizes every aspect of the church liturgical year, to the point where, as in the Catholic Church, even devotional readings are specifically structured to carry readers on a guided journey through the Bible together. Over time, my experiences helped me appreciate that church holidays offer unique opportunities for us to see the Bible as a grand overarching story, one we as believers still play an active role in.

During Advent, we consider the themes of hope, faith, joy, and peace as we anticipate the coming of Christ. The hope of redemption is realized with the arrival of Christmas and the gifts of the magi at Epiphany. A few months later, we examine our own human limitations and the sinfulness of the world that required Christ’s sacrifice through Ash Wednesday and Lent. Holy Week deepens this practice by recounting the events leading to the crucifixion. For five days, we experience the profound drama of Jesus’ pain, Judas’s betrayal, and the disciples’ fear, anger, and sorrow. Easter finishes the cycle as we celebrate the triumph of the resurrection and the beauty of God’s unconditional love.

The journey doesn’t end there. Ascension Day celebrates the resurrected Jesus and presents the beginning of the disciples’ ministry as Jesus returns to the Father. This moment further validates Christ’s divine nature, while leaving the disciples—and us—asking, “What now?” Pentecost answers that question with a miraculous expansion of God’s family, urging us to consider the diverse nature of the modern church.

All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day widen the scope, moving beyond the Bible to consider the “great cloud of witnesses” who have furthered the work of the church in the world and in our own lives. Together, these events in the church year weave an epic saga from Christ’s conception to the continuation of the ministry he began, to our roles in it now. To paraphrase Sayers’s words, it is dogma as drama.

Dogma, Drama, and Cinema

Questions of purpose, belonging, morality, and humanity aren’t isolated to the Bible, nor is the concept of individual, self-contained parts making up a larger whole. Many examples of popular storytelling ask these same questions and come to similar (and sometimes challenging) conclusions.

Filmmaker Nathaniel Dorsky describes devotional practice as an “interruption that allows us to experience what is hidden, and to accept with our hearts our given situation.” Like a devotional practice, cinema can, in Dorsky’s words, “open us to a fuller sense of ourselves and the world”3 by revealing previously unrealized truths, serving a similar purpose to a religious text or ancient wisdom literature.

Because the Bible contains so many universally powerful themes, it’s not uncommon to find connections between the art we love and the church traditions we grow up with. I discovered this at a pivotal Maundy Thursday service in high school. As I listened to a member of the congregation tell the story of the Last Supper and Jesus’ arrest, I felt a pang of emotion, a bittersweet mix of sadness, fear, and anger I instantly knew I’d felt somewhere before: watching the final scenes of Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

At the end of Fellowship, our heroes are scattered to the winds. Their leader, Gandalf, has been killed in the caves of Moria. Another member, the embattled Boromir, is dead at the hands of the orcs. Two others, Merry and Pippin, have been taken prisoner. Frodo, the ringbearer, is entering the hardest part of his journey with only his friend Sam by his side. As viewers, we know their mission will succeed—it has to—but in that moment, the future looks bleak and uncertain.

Listening to the story of Maundy Thursday as a teenager, I could easily imagine Jesus’ disciples feeling the same way. Just days before, they were welcomed into Jerusalem with joyful celebration. Now, their teacher is gone, soon to be killed, following the betrayal of one of their own. Jesus’ family and closest followers mourn that loss, but also know their own lives are in danger. In my modern context, I knew Christ would return from the dead and ascend to heaven, fundamentally changing the nature of humankind’s relationship to God. But like the disciples, in that moment all I could feel was darkness.

Given the Catholic faith of The Lord of the Rings author J. R. R. Tolkien, this connection was likely intentional. Certainly, Gandalf’s return in The Two Towers has echoes of Jesus’ resurrection. But for me, that experience in church was the first of many.

From Pew to Screen

Because popular culture echoes its audience’s interests and fears, it’s inevitable that there’s a commonality between what art is expressing and the ideas we as Christians carry with us and engage with every Sunday—even in art that doesn’t come from an explicitly religious perspective. Watching movies from a Christian perspective may make certain dramatic beats hit harder as we make connections between what we see on screen and what we talk about in church.

For instance, seeing heartbroken thirteen-year-old Kayla in Eighth Grade react to her dad’s declaration that he wishes she could see herself the way he sees her becomes more moving in light of Psalm 139 (“You have searched me, Lord, and you know me”) and the knowledge that this is how God sees us. Considering the Paddington4 films through the lens of 1 John 4:19 (“We love because he first loved us”) gives the film’s bear hero an extra layer of marmalade-sweetness. Paddington loves his neighbors not just because he’s been told to, but through the example of others who have loved him.

Encountering a resonant moment in a film can also help familiar biblical passages or seasons of the church year gain a renewed sense of immediacy or applicability. Witnessing the sacrifice of the characters in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story5 may better connect us to the disciples’ feelings of vulnerability and uncertainty at the crucifixion. The pain of loss and the hope of resurrection in the ending moments of The Iron Giant6...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Schlagworte | Advent • All Saints Day • anglican • Arts • Ascension • Ash Wednesday • Avatar • Barbie • calendar • christianity and pop culture • Christmas • christmas movies • church calendar • College • college bible study • Culture • discussion • Easter • epiphany • Faith • Fast • fast furious • Film • film critic • Furious • Galaxy • Group • Guardians • guardians galaxy • Lent • Liturgical • liturgical calendar • ministry ideas • ministry leader • Movies • Narnia • Pastor • Pentecost • Pop culture • small group leader • souls • Star Wars • watch party • Youth |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0785-1 / 1514007851 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0785-3 / 9781514007853 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich