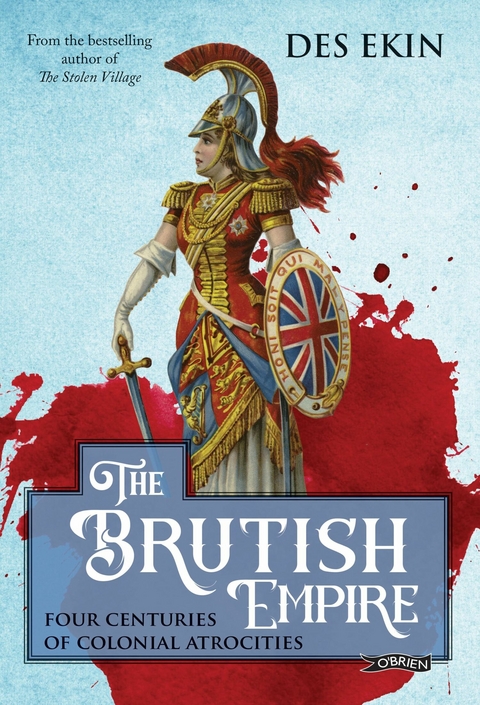

The Brutish Empire (eBook)

416 Seiten

The O'Brien Press (Verlag)

978-1-78849-546-2 (ISBN)

Des Ekin is a retired journalist and the author of four books. Born in County Down, Northern Ireland, he began his career as a reporter. After spending several years covering the Ulster Troubles, he rose to become Deputy Editor of the Belfast Sunday News before moving to his current home in Dublin. He worked as a journalist, columnist, Assistant Editor and finally Political Correspondent for TheSunday World until 2012. His book The Stolen Village (2006) was shortlisted for the Argosy Irish Nonfiction Book of the Year and for Book of the Decade in the Bord Gais Energy Irish Book Awards 2010. He is married with a son and two daughters.

October 1865. It is a stiflingly hot morning in the sleepy town of Bath, southeast Jamaica. British colonist troops have been despatched to crush an uprising among starving plantation workers at nearby Morant Bay, and the entire area is under martial law.

Cecilia Livingstone and her husband Jasper have been sheltering at home with their family, but they’ve no food left, and Cecilia, four months pregnant, is worried about her unborn baby. They know that gangs of soldiers are rampaging through the countryside, hanging and flogging civilians and even murdering a blind man as he sat in his doorway. But the couple decide, despite all the risks, to go into town to pick up supplies.

The store is closed. They wander around to the side gate to see if the owner will let them in. Their timing could not be worse. At that precise moment, a military patrol appears on the street. The soldiers seize the couple on a trumped-up charge of burglary. Jasper is hauled off and flogged, then summarily executed.

The soldiers turn their attention to Cecilia. She cries out that she’s an expectant mother. The patrolmen don’t care: at that stage their aim is to instil terror throughout the community, and how better to do that than to flog a pregnant woman with a special whip of knotted piano wire?

Cecilia screams as the vile lash rises and falls, but she takes hope when a superior officer storms up to admonish his men. ‘This won’t do to flog the women,’ he snaps, pulling the wire whip away. And then, coolly and calmly, he orders the punishment to resume … using a regular naval cat-o’-nine-tails to administer the full twenty-six lashes.

The same decade, on the other side of the world. Settlers in Queensland, Australia, find one of their cows killed by an aborigine’s spear. A white officer leads a force in retaliation. When they find an indigenous community living in caves on a mountaintop, the troopers flush them out and herd them towards a precipice, where many of them are forced to leap to their deaths. Among them is a young mother carrying her little daughter, aged two or three, in her arms. The mother dies in the cliff plunge, but her child somehow escapes death, becoming the only survivor of the massacre at a spot that is still known as ‘The Leap’.

Same decade. North Island, New Zealand. British colonist forces have illegally invaded Māori lands in contravention of a treaty. Rather than engage a waiting force of Māori warriors, they sneak past in the dead of night and instead target Rangiaowhia, an undefended town that has been set aside as a safe haven for Māori wives and children. The troops gallop into town at dawn, carbines blazing, and slaughter anywhere between a dozen and a hundred villagers.

Unless you are a history buff, you will probably never have heard of the Bath atrocities, or the horror at the clifftop at Mount Mandurana. You may be familiar with the massacres of civilians at Wounded Knee or My Lai, but it’s a fair bet that you have never heard of the massacre at Rangiaowhia. I certainly hadn’t known much about these episodes before I began researching this book.

Yet, shocking as they are, these three events – all occurring within thirty-eight months of each other – were nothing special in the history of the British Empire, the most powerful empire the world has ever known. They were just background noise, part of the continuous pattern of colonial brutality that kept the engine of Empire running smoothly for hundreds of years.

And the 1860s were not unusual or exceptional. We could have zoned in instead on the previous decade, when British colonists in India sewed Muslim citizens into pig carcasses, and forced pork into their mouths, before hanging them. Hindus were strapped to cannons and blown into fragments to ensure they could never receive a ritual funeral.

Or we could have focused on the 1840s, and the First Opium War in China. In one of the most shameful chapters of Empire history, British colonist forces bombarded cities into submission and then swept through villages, sacking, looting and raping womenfolk, in a conflict sparked off by China’s refusal to accept British opium. And, amazingly, the Opium War wasn’t even the worst thing that happened in the British Empire that decade: it was also the beginning of Ireland’s Great Hunger, when a million people died, and at least a million others were forced to emigrate.

Empire was not just a world of epic conquests, grand battles and famous generals. It was also a world in which innocent civilians, male and female, young and old, would be targeted at random for whippings, beatings or humiliations, simply because some half-crazed regional governor wished to make a point; where children could be pulled out on a whim from their school classrooms and flogged until their backs rose with bloody welts, simply as a means of intimidating their parents into obedience; where enslaved workers could be placed in a barrel driven through with sharp nails and rolled downhill. All of these things were designed to enforce the unquestioned supremacy of British colonist rule.

‘Frightfulness’ is a word we rarely use today. It sounds like a term that some overwrought interior designer might use to criticise a rival’s décor scheme. But at the peak of Empire, it had a different, and much more sinister, meaning.

‘What I mean by frightfulness,’ Winston Churchill told the House of Commons in 1920, ‘is the inflicting of slaughter or massacre upon a particular crowd of people, with the intention of terrorising … the whole district or the whole country.’ Having said that, he assured the House that ‘frightfulness is not a remedy known to the British pharmacopoeia … the august and venerable structure of the British Empire … does not need such aid. Such ideas are absolutely foreign to the British way of doing things.’

But, as the astute Churchill probably knew all too well, frightfulness (or state terrorism as we might call it today) was very much part of the British colonial way of doing things. It was the unwritten page-one in the user’s guide to Empire.

The philosophy was summed up by Reginald Dyer, the general responsible for one of the Empire’s most notorious massacres – in Amritsar, India, in 1919. After ordering his troops to open fire into a crowd of unarmed civilians, killing anywhere up to a thousand of them, he explained at an inquiry that he was trying to achieve ‘a moral effect’.

Was this an example of ‘frightfulness’? he was asked.

He countered: ‘It was a merciful act, though a horrible act, and they ought to be thankful to me for doing it … I thought it would be doing a jolly lot of good and they would realise they were not to be wicked.’

* * *

As a child growing up in County Down, I had never thought much about the British Empire. It was something that loomed large in the background, like the Mourne Mountains, but it was rarely discussed.

Aged eight or so, I discovered a children’s history book that had been published at the height of Empire in the early 1900s. It was called Our Island Story, and it was a rollicking, action-packed account of British imperial history. I drank in all the thrilling stories of heroic battles and derring-do, of scheming tribal leaders conquered by red-coated heroes, of beleaguered forces saved from starvation by bagpipe-playing reinforcements. I emerged from the experience with the impression that Britain’s conquest of a fourth part of the world had been something almost inevitable, like the weather. It was certainly not a history to be questioned.

The first globalisation: an early-1900s booklet boasts of the Empire’s scope and displays the crests of every major colony.

In my early teens, the first shadows of doubt began to cross my mind. In a memoir by Brendan Behan, I encountered the unfamiliar placename ‘Amritsar’. Curious, I looked it up and read for the first time the horrifying story of Dyer’s massacre of hundreds of innocent civilians in India.

I was a voracious reader, and the more I read, the more I felt the ground shift under my feet as the narrative of the benign, heroic, civilising British Empire began to subside, undermined by uncomfortable truth. Of course, I’d known about the Great Hunger in Ireland, but I had never realised the full extent of the then British government’s culpability. It had not only (in the later words of Tony Blair) ‘stood by while a crop failure turned into a massive human tragedy’. Victorian politicians had actually welcomed the catastrophe as an opportunity to apply their lunatic theories of social engineering. Even the claim that Britain had been the first country to end the transatlantic slave trade turned out to be untrue.

By the time I reached adulthood, I was a full-blown sceptic. A permanent move to Dublin in the Irish Republic immersed me in an atmosphere that was, understandably, much more Empire-critical. With good reason, people had learned about the excesses of British imperialism at their mothers’...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Wirtschaftsgeschichte |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | British • Colonial • Colonisation • Empire • History |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78849-546-2 / 1788495462 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78849-546-2 / 9781788495462 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 22,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich