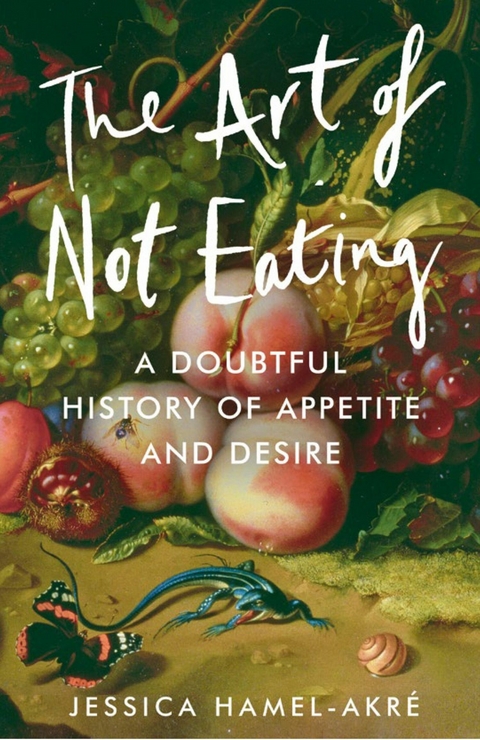

The Art of Not Eating (eBook)

320 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-705-6 (ISBN)

Jessica Hamel-Akré is an award-winning historian, researcher and cultural strategy consultant. She holds a PhD from the University of Montreal and was a postdoctoral scholar in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge and Newnham College where she conducted a seven year study on the history of appetite control. An expert in the history of women's health, literature and feminist thought, she has helped some of the world's biggest brands navigate emerging ideas around gender, digital wellbeing and beauty. Jessica co-created and presented on the BBC Radio 4 documentary The Unexpected History of Clean Eating.

Jessica Hamel-Akré is an award-winning historian, researcher and cultural strategy consultant. She holds a PhD from the University of Montreal and was a postdoctoral scholar in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge and Newnham College where she conducted a seven year study on the history of appetite control. An expert in the history of women's health, literature and feminist thought, she has helped some of the world's biggest brands navigate emerging ideas around gender, digital wellbeing and beauty. Jessica co-created and presented on the BBC Radio 4 documentary The Unexpected History of Clean Eating.

1.

A Text

HE WAS THE most obese man in eighteenth-century England and I fell in love with him in 2014. ‘Obesity’ wasn’t my term. It belonged to Dr Cheyne’s biographer, and other more established historians, who used it easily, and for whom it was merely descriptive with no contemporary ripple. I tried to be careful about these types of words. I focused on words, ideas, rather than ‘facts’. I asked myself daily if words were political, dated or postmodern; if they were feminist enough or if they were not. I asked myself at night, too, when I lay awake second-guessing myself.

My job was to undo concepts as if I were breaking apart a machine – to find truth in ambiguity. Too often, though, I took words apart without knowing how to replace them, leaving me with nothing to fill their absence. I spent my time sitting at a desk, lingering in libraries in Cambridge where I worked as a researcher and, before that, in Montreal. I often rambled around while I wondered, just wondered, about so many different things. Sometimes I wrote them down. Sometimes I told people. Sometimes I just muttered them quietly to myself. Most often, I wondered about being a woman.

I was at that time engaged in a historical and literary study of women’s appetite control and the body. It suited me to traffic in ideas professionally. This was a habit I’d had since I was a child. When I was eleven, I’d read a picture book about eating disorders – the sort of large cardboard how-to discovery book you could hold tightly against your chest and cover your torso with completely as you walked down the hallway, both hiding the front cover of your book and your budding awareness of the pains of being in a female body. When the elastic waistband of my cheap clothes cut into my expanding hips, I could not have yet known if I was growing in a way I should or shouldn’t be. It all seemed so uncomfortable and public.

It was 1997, the height of a late twentieth-century epidemic that feared for the well-being of young girls like me. News reports and TV specials flashed out warnings and, like them, the glossy pages of my little encyclopaedic book sought to teach me of the wrong way to not eat. An authorless, didactic voice. An earworm: This is what anorexia is; this is what bulimia is; this is the type of girl who is prone to anorexia; this is the type of girl who, slightly less admirable than her counterpart, is usually bulimic. This is the sadness of their families and the conflicts of their friendships.

Their words encapsulated me before I had the chance to find out who I might be in another way. They made it seem so straightforward, so firm, these lessons of who not to be and what not eating had to do with it. Yet, I admired these girls; well, the anorexic girls more than the bulimic ones. I wanted to be more type A, and not B. There was nothing unique about it. I believed in the sincerity of the fictional experience of the disordered, but well-intended, young female characters who were so often presented to me on TV and in books. With thoughts then fractionally absorbed by an adolescent’s mind, it seemed what was necessary to learn was to control the body through appetite. And that appetite was a text through which the body spoke. That there was a whole history contained within this windswept idea was still much beyond my scope of understanding. That would come later. For the time being, I simply stood with increasing regularity in the blue midnight glow of the fridge and ate in obscurity as I saw my mother frequently do, never knowing what compelled me – if it was the books, mimicry or an innate frustrated hunger. Today, this distinction remains difficult to make. I’ve always lacked a taste for intellectual minimalism.

From a young age, I knew I wanted to be serious. I thought I needed to be in control of whatever fell under my realm of action. The margins of error felt small from early on and the world around me seemed unforgiving of girlish mistakes and indulgence. In my quest to embody this quality, I needed to understand what I was supposed to control and what I couldn’t. My body, they – this grand they – told me, was in need of the most control. I listened. I would practise telling and enacting a series of stories until, one day, I could convincingly say: I was now a woman who could finally forget she was a body and get on with life. I would know how to lust without feeling. I would know how to ache without pain. I would be disciplined. I would be orderly. I told myself I would know how to not eat with ambivalence and no longer need to acknowledge all that implied. This perspective would eventually prove temporary, however. While, back then, my little book said that some girls might die from not eating, it avoided telling me what happened to the girls who lived somewhere between virtue, vice and excess, and that this was where I would likely end up oscillating. It never told me what type of woman I risked becoming. In his own way, Dr George Cheyne would tell me who I was fated to be more effectively than any other.

In a beige room, as functional as it was uninspiring, I sat awkwardly, my feet softly swinging beneath an ageing oval office table. I looked down at him. He was just a name on a syllabus, but that same night he became so much more to me.

Already a ghost, Cheyne was the author of a dusty essay in an anthology of texts on melancholy, assigned reading in my graduate studies literature course on eighteenth-century health. The first words I read by him were in excerpts from his 1733 medical treatise and opus, The English Malady. His text was one of a few intended to illustrate how contemporary conversations on mental health emerged and evolved over the centuries. My professor pointed to the differences in the languages of then and now. We say depression; they say nervousness. Our bodies are hormonal; theirs were humeral. They were different, but sometimes the same. These thought experiments were meant to test the historian’s mindset. ‘Try to imagine what your body could be if it was filled to the brim with black bile, if you believed it to be true. Imagine your menstrual cycle could reveal who you were inside’, or so I heard. Easy, I thought next. I already did.

Dr Cheyne was best known for his recommendations that restrictive and selective eating, adhering to a vegetarian-style diet, could heal a range of physical and mental ailments, especially those coming from nervous disorders, like melancholy or hysteria. Hidden in his warnings, I would see, though, was something unspoken. Unofficial. He laid out a course long ready for me in anticipation of the day when I would find it and go along, moving backwards in time to be nearer to him. When he reached his hand out towards me, I followed where he led, progressively more exposed beneath an unravelling myth of self-containment.

Born in 1672 in Aberdeenshire, Dr Cheyne’s family intended for their son to lead a clerical life from an early age. Instead, he chose the well-trodden path of a gentleman intellectual, one full of missteps along the way. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Aberdeen. Initially, he attempted a career in mathematics, but it failed to take off. His early books garnered little interest. Eventually, he turned to medicine and soon joined the fashionable circles of England. Dr Cheyne treated Britain’s upper classes in London and the spa town of Bath where he advised on the bodies of aristocrats and those in political families. He doctored philosophers and novelists, poets and prophets. When I began to explore the details of Dr Cheyne’s life, they first seemed inconsequential, but I soon learned that, through his many connections, his ideas about the human appetite spread among the most enviable and influential; those who, in one way or another, were, like Dr Cheyne, writing the rules of science and rationality for the modern society we would come to live in.

His unique and admittedly unconventional practice became so popular that it birthed new ways of expressing and experiencing pain and feeling. He was everywhere in early eighteenth-century high society, frequently among the likes of Alexander Pope, David Hume, Robert Walpole, Sir Hans Sloane and Samuel Richardson.

I read his writing from a second-hand chair in the corner of the small triplex apartment in Montreal that I shared with my husband, the book resting on my knees. Traffic buzzed. Buses stopped and went; occasionally they got stuck in the snow. Feet squelched in slush. A man muttered so loudly that his murmurs pierced through our closed window, but that was normal in the city. The noises came as they went, quickly, while I sat alone in the company of Dr George Cheyne. A mundane assignment soon became something else – a force that gently swept me away. This was, in fact, his speciality – helping people forget and find themselves.

Despite his medical profession, Dr Cheyne was a literary type, too. In the close relationships he built with his patients, in particular the famous writers he doctored, the robust editorial voice he used to improve their bodies also sought to improve their stories. His medicine was metaphorical, endlessly moral and mystical. The influence of the Anglican clerical studies he completed in his youth was present in his medical practice. When he doctored the body, one whose standards of health were set according to the norms and aspirations of male bodies, he doctored the soul. And he worked through the mind with language.

In The English...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | Black and white integrated illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Schlagworte | Alexander Pope • amia srinivasan • Angela Saini • Anorexia • Appetite • beauty myth • best new history books • best new history books 2024 • best new memoirs • binge eating disorder memoirs • books about diet • books about diet culture • books about eating • books about eating disorders • bullmia • Charlotte Gordon • chris van tulleken • Clarissa • Clean Eating • cultural history books • Desire • diet • eating • eating disorder memoirs • Eating Disorders • eating disorders in history • eating disorders throughout history • femininity • Feminism • Gender • george cheyne • history of diet culture • history of eating disorders • how to write about eating disorders • Maggie Nelson • Mary Shelley • Mary Wollstonecraft • new nonfiction books 2024 • Olivia Laing • processed foods • Samuel Johnson • Samuel Richardson • Sexuality • ultra processed food • ultra processed people • why is ozempic dangerous • why is ozempic so popular • Wolf |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-705-7 / 1838957057 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-705-6 / 9781838957056 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich