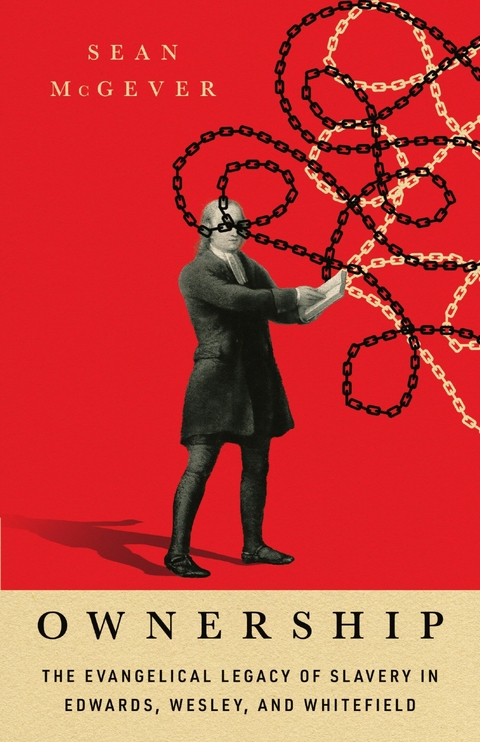

Ownership (eBook)

240 Seiten

IVP (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0416-6 (ISBN)

Sean McGever (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is an area director for Young Life in Phoenix, Arizona, and adjunct faculty at Grand Canyon University. He is the author of several books, including Born Again: The Evangelical Theology of Conversion in John Wesley and George Whitefield and Evangelism: For the Care of Souls.

Sean McGever (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is an area director for Young Life in Phoenix, Arizona, and adjunct faculty at Grand Canyon University. He is the author of several books, including Born Again: The Evangelical Theology of Conversion in John Wesley and George Whitefield and Evangelism: For the Care of Souls.

2

Three Men Who

Would Change

the World

JONATHAN EDWARDS, GEORGE WHITEFIELD, and John Wesley together provided the foundation of American evangelical Christianity. Consider the highly regarded recent five-volume A History of Evangelicalism, of which the first volume is subtitled “The Age of Edwards, Whitefield, and the Wesleys.”1 A thorough discussion of American Christianity, modern British Christianity, and even modern world Christianity requires an examination of these three figures.2 These men share many similarities, and their stories are interwoven, even as they’re also quite different from each other. As this book unfolds, you will see how we must understand all three men together to make sense of slavery and evangelical Christianity in the eighteenth century—and to make better sense of Christianity today.

These three men lived in the same era. In fact, John Wesley was born just 99 days before Jonathan Edwards. While the Atlantic Ocean separated them—except for a brief chapter—the fact that they were born in the same year gives us a plumb line to compare their lives, their influences, their reactions to events in the Atlantic world, and the interactions between England, colonial America, and beyond. We can imagine George Whitefield as Wesley and Edwards’s little brother since he was born eleven years after them, in 1714. These three men lived in a dynamic time that is the foundation for all of evangelical Christianity.

A second similarity shared by these three men is their focus. The ministerial focus of all three of these men was clear: conversion. For them, conversion—the evidence of the new birth and of eternal salvation—is the experience through which every genuine Christian must pass; conversion was the “one thing needful.”3 Historian Thomas Kidd writes, “[the] distinctive belief of evangelicals is that the key moment in an individual’s salvation is the ‘new birth.’”4 Their focus on the individualistic experience of the new birth, generally opposed to a more passive cultural Christianity, is the foundational doctrine that links them and the early evangelical movement together.

A third similarity among these men is their direct and extended relational networks. John Wesley met George Whitefield when Whitefield arrived at Oxford in 1734 and joined the Holy Club. George Whitefield met Jonathan Edwards on Whitefield’s second preaching tour across colonial America in 1740. Wesley and Edwards never met face-to-face, yet they read each other’s writings, and Wesley even edited and republished five of Edwards’s works. (Wesley’s assessment of Edwards was dire. Wesley warned that in Edwards’s work “much wholesome food is mixt with much deadly poison.”5) Wesley and Whitefield remained in frequent communication until Whitefield’s death. Wesley preached Whitefield’s funeral eulogy—near the climax of Wesley’s thoughts on slavery, as we will see. Whitefield and Edwards would meet face-to-face a second time, and their ministries brushed shoulders frequently.

Beyond their direct relationships, the networks around these three men formed a “who’s who” of early evangelicalism. In recent years, scholars attempting to define evangelicalism have fought for firm criteria. Scholars of early evangelicalism usually start with David Bebbington’s quadrilateral of conversion, activism, crucicentrism, and biblicism. Scholars of recent evangelicalism typically highlight the highly political nature of American evangelicalism beginning around 1980 and the fracturing of evangelicalism regarding race; modern politically charged American evangelicalism shares little affinity with the theological and spiritual foundations of early evangelicalism. The relational origins of evangelicalism provide another approach to understanding evangelicalism. Scholar Timothy Larsen explains that an evangelical is one “who stands in the tradition of the global Christian networks arising from the eighteenth-century revival movements associated with John Wesley and George Whitefield.”6

Apart from their many similarities, these three men each possessed unique gifts—among the most impressive in the entire history of Christianity. Wesley was one of the most effective organizers the church has ever seen. Edwards is among the most powerful Christian thinkers, theologians, and philosophers. Whitefield preached as powerfully and passionately as anyone. Wesley and Whitefield were ministers of the Church of England; Edwards was a Congregationalist. Edwards and Whitefield were Calvinistic in their theology; Wesley was an Arminian. Edwards and Wesley spent most of their lives on their respective home continents; Whitefield made thirteen transatlantic trips.

The popular relevance of each man has waxed and waned over the centuries. Whitefield owned the eighteenth century with his dynamic preaching, boundary-pushing ministry, and celebrity status. Wesley had a significant influence during his lifetime, but nothing compared to the explosive growth and influence of Methodism, the movement birthed out of his ministry, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. And the influence of Edwards has been on the rise in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries in a way that was hidden earlier.

John Wesley was the first one born and the last one to die among them. His life spans Whitefield’s and Edwards’s—by a lot. Wesley’s life is a lens through which we see how White British and American evangelical Christians in the eighteenth century thought about and engaged in slavery. It is with his story that we will begin. As you read the rest of the chapter, look for the formative influences these men were born into and accepted along the way as we seek to understand and own the evangelical legacy of slavery and how it eventually changed.

INTRODUCING JOHN WESLEY

John Wesley is the central figure of our examination of early evangelicals and slavery because he lived long enough and documented his life extensively for us to see how one person reacted to several pivotal eras of evangelical responses to slavery. Wesley is the key figure to understanding the past of evangelicals and slavery.

John Wesley rode 250,000 miles on the roads of England, Scotland, and Ireland to preach 42,000 sermons. He published 233 books. He grew Methodism from a Bible study of four members to 132,000 people—72,000 in the British Isles and 60,000 in America—by the end of his life. Modern Methodist churches in America are in decline, but the ecclesial legacy of Wesley is much wider. Wesleyan origins are found in a wide range of churches, including United Methodists, Nazarenes, Free Methodists, Salvation Army, Holiness, Pentecostal, and Methodist churches around the world that make up 80 different denominations and more than 80 million people worldwide.7 In 2019, there were about three times the number of Methodists in Ghana than in Great Britain and as many in Africa as in the United States.8

Wesley’s teaching on instantaneous perfection provided the theological and ecclesial roots of Pentecostalism. Methodists stressed the pursuit of holiness, and some groups understood the gift of tongues as evidence of a miraculous breakthrough in Christian growth—creating Pentecostalism.9 Pentecostalism (and the related charismatic movement) is the fastest growing form of Christianity, with more than 644 million adherents in 2020, representing 8.3 percent of the world population. This includes 68 million people in North America, and an astounding 230 million people in Africa, 195 million in Latin America, and 125 million people in Asia. The total number is expected to surpass one billion people by 2050.10 Wesley’s influence on not only American Christianity but world Christianity might be larger than any other Christian leader in the last three centuries. Even if you aren’t aware of Wesley’s direct influence, you are still surrounded by it.

John Wesley was the fifteenth child of Samuel and Susanna Wesley. He was born on June 17, 1703, in the Epworth rectory in Lincolnshire, England. His father was a priest in the Church of England and, like his wife, had come from a long line of nonconformist ministers steeped in the Puritan tradition—which would be relevant to John’s formative outlook on slavery.

Samuel Wesley had been a servitor—a servant to rich students—to pay for his education at Oxford. Later, Samuel wrote a weekly newspaper advice column, one time answering the question: “Whether trading for Negroes, i.e. carrying them out of their country into perpetual slavery, be in itself unlawful, and especially contrary to the great law of Christianity?”11 Samuel’s response began by saying that doing so is “contrary to the law of nature, of doing unto all men as we would they should do unto us.”12 The rest of his answer worked through biblical and logical arguments combined to make a clear denunciation of man-stealing and, thus, slave trading. He published these arguments a decade before John’s birth.

Susanna’s father had been a minister at St. Paul’s Cathedral and pastor to Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe—a story in which the main character is enslaved and later sets out to enslave others. Defoe published a flattering poem about Susanna’s father. Thus, John’s parents were aware of slavery, the slave trade, and the questions English Christians asked about these issues—though they had no firsthand involvement or contact with enslaved people as far as we know.

Susanna raised...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Vincent E. Bacote |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | American • American Evangelicalism • American History • Bible • Biblical • Biography • Black • Calvinist • Christianity • christianity and slavery • Church • Church history • Colonial • colonies • Early • evangelicalism • George • George Whitfield • History • History of Evangelicalism • johnathan • John Wesley • Jonathan • Jonathan Edwards • New England • quaker • Race relations • Racism • racism in America • Religion • Religious beliefs • slave owners • slavery in America • Studies • whitfield |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0416-X / 151400416X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0416-6 / 9781514004166 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich