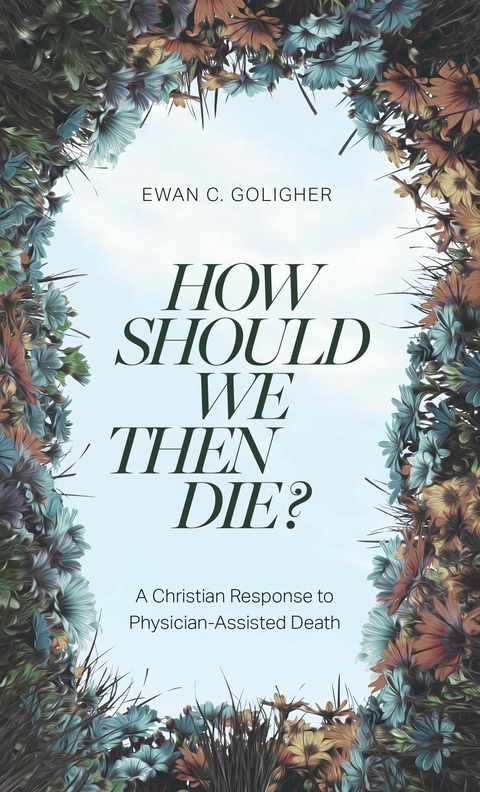

How Should We then Die? (eBook)

160 Seiten

Lexham Press (Verlag)

978-1-68359-748-3 (ISBN)

- Explains why physician-assisted death is attractive

- Makes a case for the value of life and wrongness of killing

- Argues from general revelation and Scripture

- Helps Christians undercut the logic of euthanasia

As more people accept the practice of physician-assisted death, Christians must decide whether to embrace or oppose it. Is it ethical for physicians to assist patients in hastening their own death? Should Christians who are facing death accept the offer of an assisted death?

In How Should We then Die?, physician Ewan Goligher draws from general revelation and Scripture to persuade and equip Christians to oppose physician-assisted death. Euthanasia presumes what it is like to be dead. But for Christians, death is not the end. Christ Jesus has destroyed death and brought life and immortality through the gospel.

Ewan C. Goligher (MD, University of British Columbia; PhD, University of Toronto) is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and has published over 150 papers and several book chapters. As a physician practicing critical-care medicine, he is regularly involved in helping patients and families navigate difficult decisions about medical care at the end of life.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Bellingham |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Schlagworte | Christian Ethics • christianity and euthanasia • christians and suicide • end-of-life • euthanasia • Pro-life • Suicide |

| ISBN-10 | 1-68359-748-6 / 1683597486 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-68359-748-3 / 9781683597483 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich