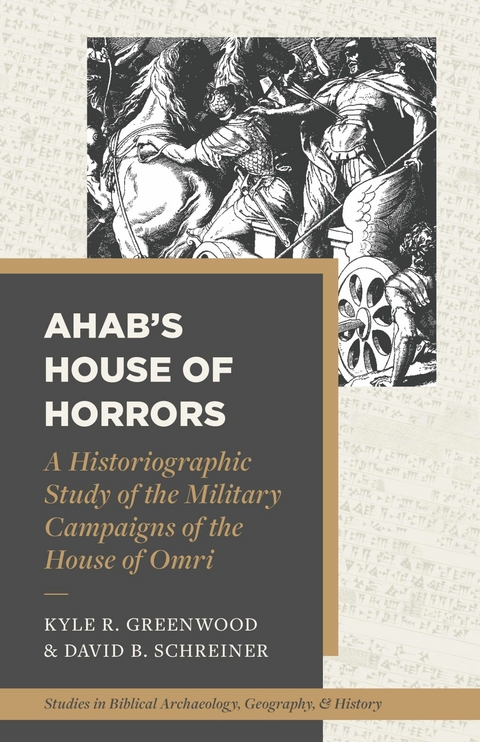

Ahab's House of Horrors (eBook)

176 Seiten

Lexham Press (Verlag)

978-1-68359-649-3 (ISBN)

The extrabiblical testimony surrounding Israel's early history is difficult to assess and synthesize. But numerous sources emerging from the ninth century BC onward invite direct comparison with the biblical account. In Ahab's House of Horrors: A Historiographic Study of the Military Campaigns of the House of Omri, Kyle R. Greenwood and David B. Schreiner examine the historical records of Israel and its neighbors. While Scripture generally gives a bleak depiction of the Omride dynasty, extrabiblical evidence appears to tell another story. Inscriptions and archeological evidence portray a period of Israelite geopolitical influence and cultural sophistication.

Rather than simply rejecting one source over another, Greenwood and Schreiner press beyond polarization. They propose a nuanced synthesis by embracing the complex dynamics of ancient history writing and the historical difficulties that surround the Omri dynasty.

Ahab's House of Horrors is an important contribution to the ongoing discussion of biblical historiography and, specifically, to our understanding of 1–2 Kings and the Omri family.

Kyle R. Greenwood is administrative director of the master of arts program for Development Associates International and affiliate associate professor of Old Testament at Fuller Theological Seminary. He is the author of Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science. David B. Schreiner is associate dean and associate professor of Old Testament at Wesley Biblical Seminary and author of Pondering the Spade: Discussing Important Convergences between Archaeology and Old Testament Study and 1 and 2 Kings (Kerux Commentary).

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.3.2023 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Studies in Biblical Archaeology, Geography, and History |

| Verlagsort | Bellingham |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Schlagworte | 1 and 2 Kings • Bible and historiography • israel’s history • is the Bible reliable • the bible and archeology • the bible and history |

| ISBN-10 | 1-68359-649-8 / 1683596498 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-68359-649-3 / 9781683596493 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 10,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich