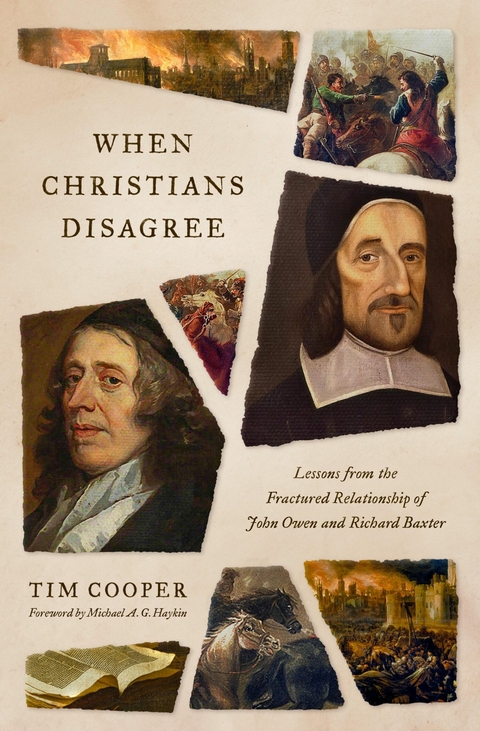

When Christians Disagree (eBook)

184 Seiten

Crossway (Verlag)

978-1-4335-9296-6 (ISBN)

Tim Cooper (PhD, University of Canterbury) serves as professor of church history at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He is the author of John Owen, Richard Baxter and the Formation of Nonconformity and an editor of the Oxford University Press scholarly edition of Baxter's autobiography.

Tim Cooper (PhD, University of Canterbury) serves as professor of church history at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He is the author of John Owen, Richard Baxter and the Formation of Nonconformity and an editor of the Oxford University Press scholarly edition of Baxter's autobiography.

1

When the rich young ruler came to Jesus with his pressing question, addressing him as “Good Teacher,” Jesus responded with a question of his own: “Why do you call me good? No one is good except God alone” (Luke 18:18–19). This is important. Only God is good; none of us are good. We have many fine qualities, to be sure, and we retain the image of God, but we are flawed, deeply flawed. Even the best of us is shot through with human sinfulness and frailty. We are all vulnerable to blind spots and besetting sins. Our best efforts are colored by imperfection. There are no exceptions. Only God is good.

Yet the evident truth of Jesus’s observation does not prevent us from saying that someone is good: “He is a good man.” “She is a good woman.” We know what we mean. We do not intend to convey that such a man or woman is a model of perfection, but there is something about each one that we can say is genuinely good. Within the confines of human weakness, they are doing their best. They stand out for their presence and contribution. In these terms, John Owen and Richard Baxter were two good men. There is much to admire in their character and achievements. Even today, four centuries on, a great many contemporary Christians hold them in high esteem. In this first chapter, I want to sketch out their life story to introduce these men to you in such a way as to emphasize their many positive qualities, accomplishments, and commonalities. That is because the remaining chapters, necessarily, accentuate the negatives and draw attention to their differences. Neither man comes out of this book looking that great. While we can say that they were both good men, we must add that “no one is good except God alone.”

Early Formation

Baxter and Owen had a lot in common. To begin with, they were both Puritans, which means they were deeply committed to seeing the Church of England reformed according to the prescription laid out in the pages of the New Testament. The label of “Puritan” was deployed against them as an insult. Baxter referred to it as “the odious name,” and no one liked being called a Puritan.1 They preferred to label themselves “the godly” or “the saints.” The nickname comes from the word “purity”: Puritans sought to purify the Church of England from anything that was a merely human innovation and to see the church return to its pure form in the age of the apostles. Over the centuries, “corruption” had crept into the church as its worship and leadership structures had become ever more elaborate and complex. For the Puritans, that corruption was embodied most comprehensively in the Roman Catholic Church.

Inheritors of the sixteenth-century Reformation, the Puritans sought to re-create the initial simplicity of the church in its earliest and purest form. They also tried to purify the society around them, publicly attacking such sins as swearing, drunkenness, sexual immorality, and the failure to acknowledge Sunday as the Sabbath, a day of rest from work but filled for them with activity such as church services, prayer meetings, and discussions of the day’s sermons. Indeed, Puritans loved their sermons. They revered the Scriptures and traveled many miles to hear them preached—and not just on Sunday. But their tendency to attack sin on a societal and national level did not endear them to their “ungodly” neighbors.

Owen and Baxter were both born into the Puritan tradition, and they were born at pretty much the same time: Baxter on Sunday, November 12, 1615; Owen sometime in 1616. Baxter was raised in the county of Shropshire, far to the west of London in the Midlands near the border with Wales. For reasons he did not explain, he lived with his maternal grandfather for the first ten years of his life before moving to live with his parents. He was an only child in a family that privileged Puritan piety. Baxter shared in that piety from an early age, persuaded that the seriousness with which his parents pursued their faith by far excelled the much more profane way of life he witnessed in the community around him. Owen, one of at least six children, was also raised in a devoutly Puritan household, in the village of Stadham (today, Stadhampton), about six miles from Oxford. His father was a deeply conscientious minister in the Church of England.

Owen received an excellent education. While young, he attended a school that met in a private home within All Saints Parish in Oxford. In 1628 he entered Queen’s College, Oxford, at the age of twelve, which was not an unusually young age to begin university study in those days. Four years later he graduated with a bachelor of arts. In 1635 he graduated with a master of arts. England’s two universities (the other being Cambridge University) trained England’s ministers. By the time Owen graduated with his MA, both universities were well into a period of reform led by the archbishop of Canterbury, who was also chancellor of Oxford University, William Laud. These reforms tended to pull both the Church of England and Oxford University away from its Calvinist moorings toward a style of theology and ceremony that seemed worryingly Roman Catholic to England’s staunch Protestants. Unhappy with these developments, Owen left Oxford in 1637. This was no easy decision. It seems that this transition threw him into a state of depression (he withdrew from human interaction entirely “and very hardly could be induced to speak a word”).2 While its intensity lasted only around three months, the aftereffects lingered for several years.

Baxter’s education took an entirely different path. He attended a few mediocre schools in his locality, but he did not go on to university. He was persuaded to take up the offer of learning under a private tutor, who, in the event, proved wholly inadequate. But he did provide the young Baxter with two things conducive to his education: plenty of books and plenty of time to read them. Thus Baxter was an autodidact (that is, he was self-taught), but we should not underestimate his intelligence or his education. If anything, his self-discipline and lifelong inclination to compensate for his lack of university training made him only more studious and industrious. He certainly never lost his early love of reading books (and writing them!). Both he and Owen possessed a formidable intelligence, and both would deploy their considerable intellectual and literary abilities in the service of God.

Indeed, both men developed a genuine, personal faith, if again in different ways. For Baxter, he discerned a deepening awareness of God’s call on his life, even though still very young, but there was no single, decisive moment he could point to. “Whether sincere conversion began now, or before, or after” that season of general discernment, he said, “I was never able to this day to know.”3 Not so with Owen. While there is no doubting his grounding in the faith from an early age, what we might call a moment of conversion came sometime around 1642 as he listened to a sermon preached at Aldermanbury Church in London by an otherwise unremarkable and anonymous preacher. The text was Matthew 8:26, “Why are you afraid, O you of little faith?” and the sermon spoke directly to Owen’s condition. In the words of his early biographer, “God designed to speak peace to his soul.”4 The effects of his depression lifted, and he became firmly assured of grace and grounded in his faith.

Pastoral Ministry, Civil War, and Early Publications

Owen and Baxter entered the 1640s as sincere, thoughtful, and well-educated young men of around twenty-five years old, but they ventured into full adulthood at a time of growing national tension. After a century of rising inflation, the amount of taxation approved by Parliament was inadequate to fund the costs of the crown. In response, King Charles I simply bypassed Parliament to pursue other means of raising revenue that were considered by many to be illegal and unconstitutional. Among the most contentious was “ship money,” a tax usually imposed on coastal towns in a time of war. In October 1634 Charles imposed ship money in a time of peace; a year later he extended the tax to inland towns. He did not summon Parliament at all from March 1629 to April 1640 in what are now called the eleven years of “personal rule,” thus clamping shut one of the most important pressure valves in representing legitimate grievance against the government. During that period, Charles and his archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, also clamped down on Puritan Nonconformity in the parishes. Ministers who refused to use the Book of Common Prayer or wear the surplice (a loose vestment of white linen that many Puritans viewed as a Roman Catholic hangover) were fined, removed from office, or imprisoned. This was the decade when many Puritans fled to New England, where they could shape a church to their liking without the interference of bishops. Those who remained felt increasingly persecuted and alienated.

Worse still, in 1637 Charles and Laud attempted to impose the same kind of conformity in Scotland. Charles was king of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and ruling multiple kingdoms posed a challenge for even the very best of politicians. Charles...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Michael A. G. Haykin |

| Verlagsort | Wheaton |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik |

| Schlagworte | Bible • biblical principles • Christ • christian living • Church • Community • Discipleship • disciplines • Faith Based • God • godliness • Godly Living • Gospel • Jesus • Kingdom • live out • new believer • Puritans • Religion • Small group books • spiritual growth • UNITY • walk Lord |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4335-9296-7 / 1433592967 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4335-9296-6 / 9781433592966 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 744 KB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich