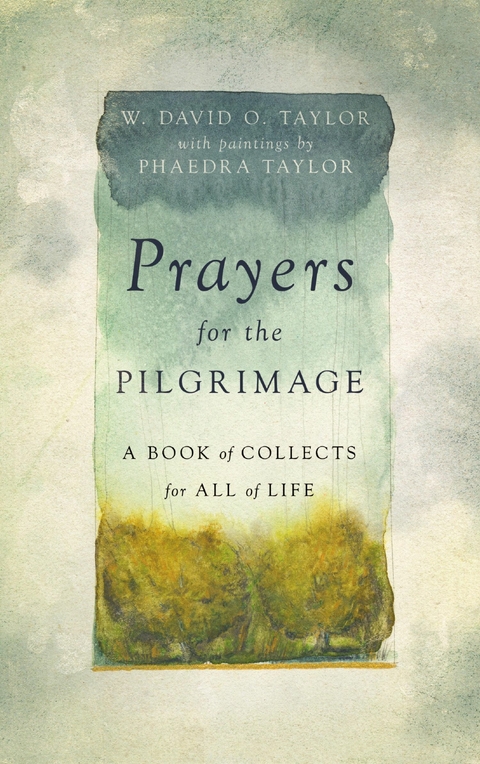

Prayers for the Pilgrimage (eBook)

224 Seiten

IVP Formatio (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0824-9 (ISBN)

W. David O. Taylor (ThD, Duke Divinity School) is associate professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary and the producer of a short film on the psalms with Bono and Eugene Peterson. An ordained Anglican minister, he is the author of Open and Unafraid: The Psalms as a Guide to Life, Glimpses of the New Creation: Worship and the Formative Power of the Arts, and The Theater of God's Glory: Calvin, Creation, and the Liturgical Arts, the co-editor of Contemporary Art and the Church, and the editor of For the Beauty of the Church: Casting a Vision for the Arts.

W. David O. Taylor (ThD, Duke Divinity School) is Associate Professor of Theology and Culture at Fuller Theological Seminary and the author of several books, including A Body of Praise, Open and Unafraid, and Glimpses of the New Creation; he is also the editor of For the Beauty of the Church as well as co-editor of Contemporary Art and the Church and of The Art of New Creation. He has written for The Washington Post, Image Journal, Religion News Service, and Christianity Today, among others. He serves on the advisory board for Duke Initiatives in Theology and the Arts as well as IVP Academic's series, "Studies in Theology and the Arts." An Anglican priest, he has lectured widely on the arts, from Thailand to South Africa. In 2016 he produced a short film on the psalms with Bono and Eugene Peterson. He lives with his family in Austin, Texas. Phaedra Taylor (BFA, University of North Texas) is an artist whose work has been exhibited in juried, group, and solo exhibitions, and is held in private collections around the globe. Together with her husband, David, she also makes creative liturgical resources for families and churches.

INTRODUCTION

I began writing collect prayers, or what is simply called a “collect,” on March 15, 2020—the day that our country shut down on account of the coronavirus. At first, it was simply a way for me to cope with my own fears over an uncertain future. I’d written such prayers here and there, and I’d assigned them over the years to my students at Fuller Theological Seminary, but I now wrote them as a kind of daily spiritual exercise, and a rather desperate one.

I wrote a prayer titled “Against the Pestilence that Stalks in the Dark,” giving voice to the language of Psalm 91, which prior to Covid-19 may have felt like something that only medieval Europeans suffering from the bubonic plague would have understood, but which now made immediate sense to us as a twenty-first-century global people. The archaic language of the King James Bible never felt so apt:

Thou shalt not be afraid . . .

for the pestilence that walketh in darkness;

nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday. (Psalm 91:5-6)

I wrote a prayer “For Dashed Plans” because it became increasingly obvious that there would be plenty of those to deal with in the months to come, resulting for some in bitter disappointment, for others in relief, grateful that they no longer needed to organize anything, at least for the foreseeable future.

I wrote prayers “For Beleaguered Parents,” among whom I counted myself, and “For Anxious Children,” including my own, who often lacked the capacity to verbally name the jumble of feelings that roiled beneath the surface of their conscious understanding. I wrote a prayer “For the Depressed” after hearing of the experiences of the elderly, like my uncle, trapped in their nursing home rooms, confused and afraid; and of single people who lived alone in their apartments without any opportunities for meaningful physical touch from others.

I also wrote a prayer “Against Neighbor Hate” after the 2020 election, hoping it might arrest an impulse that had become all too easy to indulge for many of us in America.

For me, the writing of such prayers became a way to make sense of the realities of our world in upheaval.

In time, I began to receive messages from both friends and strangers, often through social media, requesting prayers on behalf of people who deserved our very best intercessions: “For Grocers Managing Panic-Buying Shoppers,” “For Medical Professionals Overwhelmed by the Countless Sick,” “For Garbage Collectors Working Overtime,” and “For Untimely Deaths.”

When schools began to open their doors again, my bishop asked if I might consider writing a series of “Back to School Prayers,” which I did, keeping in mind the unique challenges faced not only by students but also by teachers and administrators. I published a separate batch of “Prayers for a Violent World” because our world had turned increasingly savage.

With my wife, Phaedra, a visual artist, I conceived a series of illustrated prayers that might allow people to pray not just with words but also with images—to see the shape of sorrow, to imagine the texture of death, or to perceive the beauty of feet that chose to publish peace instead of hate. For this particular venture, Phaedra and I created three sets of prayer cards for the Rabbit Room, a marvelous organization committed to cultivating creativity through community and artmaking.

Often after posting my prayers on social media, I found that they resonated with people across denominational and political lines. They gave voice, it seemed, to things many Christians believed God would never be interested in. My hope, of course, was to persuade readers otherwise—that God was, in fact, interested in hearing everything that we have to say to him in prayer.

God cares little about whether we get our prayers “right” or whether we tidy up our lives prior to making our intercessions known. True piety, as the psalmists repeatedly suggest, ought not to be a precondition for talking to God. Showing up is all that’s needed, as well as a commitment to being brutally honest with God—honest about our doubts, honest about our anger about unanswered prayers, honest about the failures and fears we might be ashamed to admit out loud, among others.

Stanley Hauerwas puts the point this way in his book of prayers, Prayers Plainly Spoken:

God wants our prayers and the prayers God wants are our prayers. We do not need to hide anything from God, which is a good thing given the fact that any attempt to hide from God will not work. God wants us to cry, to shout, to say what we think we understand and what we do not. The way we learn to do all this is by attending to the prayers of those who have gone before.1

All aspects of our lives must be prayed, then, lest we become atheists in the quotidian parts of our lives because we have come to believe that these parts are, in fact, godless, devoid of God’s interest and care. But that is not the kind of God we encounter in the Psalms, nor in the life and ministry of Jesus, whom the book of Hebrews calls the true Pray-er. He is the infinitely gracious one who eagerly welcomes our whole selves, along with all the details of our lives.

Around the two-year anniversary of the shutdown of our world that Covid-19 demanded of us, I discovered that I had written close to four hundred collect prayers. It was at this point that I wondered whether they might become a book of their own. The editors at InterVarsity Press believed that they could, and for that I am deeply grateful.

The Collect Prayer

Three questions that I’ve often answered over the past few years are: What exactly is a collect? Is it a CAW-lect or a cuh-LECT? (it’s the former). And why did I choose to work nearly exclusively with this form of prayer?

To answer the first question, a collect is an old form of prayer, concise in form and immensely useful to any circumstance of life. It is also a theologically disciplined prayer. Dating back to the fifth century, the collect is rooted in a basic biblical pattern that “collects” the prayers of God’s people.2 As C. Frederick Barbee and Paul F. M. Zahl explain:

This at-first extemporaneous prayer would later also be connected to the Epistle and Gospel appointed for the day. A Collect is a short prayer that asks “for one thing only” . . . and is peculiar to the liturgies of the Western Churches, being unknown in the Churches of the East. It is also a literary form (an art comparable to the sonnet) usually, but not always, consisting of five parts.3

The five parts that Barbee and Zahl speak of include, nearly always, the following things:

-

1. Name God.

-

2. Remember God’s activity or attributes.

-

3. State your petition.

-

4. State your desired hope.

-

5. End by naming God again.

While covering a good deal of ground, the collect is notable for its economy. It’s a blessedly short prayer. It’s short because it typically revolves around one idea only, which in principle is drawn from Scripture. In doing so, several benefits accrue to the one who prays it.

Most basically, it invites us to call to mind what God has done in the past before we make our present petitions known. We remember before we request, and we look back on the faithfulness of God in the lives of others prior to welcoming the faithfulness of God in our own.

The collect also offers an opportunity to discover how the triune God attends to the details of our lives. If the devil is in the details, as the common saying goes, God is in the details infinitely more so. God is intimately interested in those specific aspects of our lives—doing laundry, suffering illness, aging rapidly, fighting traffic, spending time with a friend—where we find ourselves actually believing, or disbelieving, that God wishes to meet us in the pain and pleasure of our life’s circumstances.

Another way of making this point is that the collect is a concrete species of prayer. It deals with one concrete thing without, hopefully, devolving to idiosyncratic vocabulary. My prayer for the pandemic, for instance, was born out of a specific experience that was foisted upon our world, but its language is “open” enough to make it useful to present-day circumstances where plague-like tragedies may require a prayer drawn from the ancient language of the psalmists.

The prayer that I wrote for Phaedra when she makes bone broth (a regular thing in our household) may not feel relevant to 99 percent of humanity. Yet the actual language of the prayer draws attention to ingredients that are, in fact, common to 99 percent of humans on planet earth: root, leaf, fish, fowl, spice, and so on. Surely, I imagine, there will be plenty of occasions to ask God to take the basic elements of creation and to bless them to our health.

The stuff of life, then, that populates collect prayers is of a concrete sort, without being distractingly subjective, and in this way the prayers offer themselves as universally accessible, capable of being prayed by all sorts of people in all manner of life settings.

Yet while I have tried to steer clear of too-subjective language in most of these prayers, it has been impossible to escape the subjective nature of the selection itself.

I am mindful,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Illustrationen | Phaedra Taylor |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Gebete / Lieder / Meditationen |

| Schlagworte | anglican • ART • Birth • children • Christian • Christian art • Christian collects • christian living • Church year • daily • Death • Discipleship • evening • evening prayer • every moment holy • Formation • God • growth • Holidays • Holy • liturgical calendar • Liturgy • Living • Love • Morning • morning prayer • Nature • Prayer • prayerbook • prayer life • relationships • school • sickness • Sin • special occasions • Spiritual • Spiritual Formation • spiritual growth • Work |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0824-6 / 1514008246 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0824-9 / 9781514008249 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich