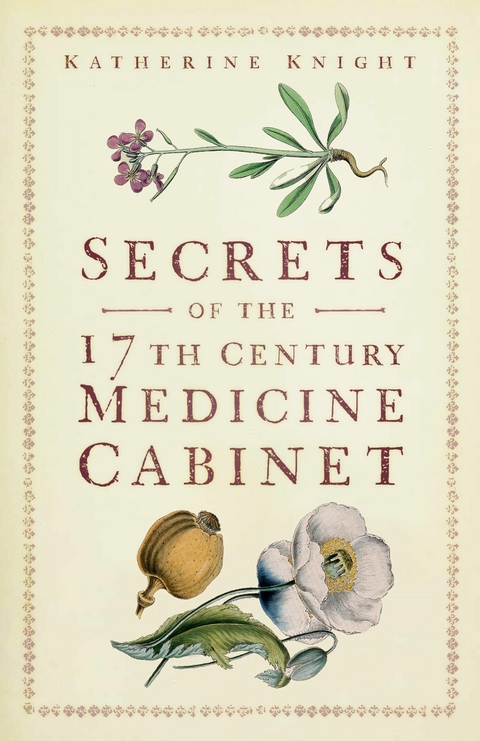

Secrets of the 17th Century Medicine Cabinet (eBook)

222 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-812-1 (ISBN)

KATHERINE KNIGHT trained as a teacher of home economics before bringing up her four children. She ran the poetry writing club at the City Lit, Holborn for many years and has now transferred the history of cooking to the history of domestic medicine. She is the author of The Mother and Daughter Cookbook and The Cookery Book Club. She lives in Strawberry Hill.

2

Background to 17th-Century Medicine

The seventeenth century was an exciting time for well-educated and enquiring men, provided they could negotiate religious fanaticism, political power struggles and the Civil War, and survive the various plagues and fevers which surrounded them. By the end of the century, Natural Philosophy covered wide fields of enquiry, from astronomy, on a large scale, to microscopy, on a very small one. Alchemy flowed from a distant past to a golden future after it was transmuted into chemistry. With hindsight, we can see that ‘science’ was not a new concept. For example, as far back as the thirteenth century Roger Bacon (c.1220–1292), had studied mathematics, optics and astronomy, as well as alchemy and languages. His work on the nature of light anticipated Newton. (The double-edged benefit of science was apparent even then: Bacon described both gunpowder and eyeglasses.) A later philosopher, coincidentally with the same name, proposed a method of inquiry depending on experiment and deductive reasoning. This was Francis Bacon (1561–1626). Many members of The Royal Society, founded after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, picked up scientific method and ran with it into the modern world.

This was just at the top of the intellectual pyramid, however. Men of high social position were frequently sent off to University, either in Britain or abroad, but the rest of the population got by with far less learning. Adult male literacy was not universal. Women were even less likely to be educated. As far as medicine was concerned, physicians were still struggling to make it a profession of high status, like Law or the Church. As in those callings, medicine had to be based on authoritative texts to be academically acceptable. A physician’s training since medieval times included liberal subjects such as rhetoric and mathematics besides classical theories of disease. Only the richest patients could consult these physicians, whose high standing was reflected in their fees. They were in competition with each other, and a person could go from one to another if he was dissatisfied with his cure.

For poorer people there were other ways of getting help without calling in an expensive doctor. You could ask for advice from your family, your neighbours or the parish priest. Some people went to the local wise woman with good results, though it was debatable if magical cures were legitimate. ‘Sorcerers are too common; cunning men, wizards, and white witches, as they call them, in every village, which, if they be sought unto, will help almost all infirmities of body and mind,’ said Robert Burton.1 He concluded that it might be better to suffer than to be damned for meddling with the devil. Given this attitude, it is surprising that ‘white witches’ were kind enough to help anyone apart from their immediate and trusted family and neighbours. An accusation of witchcraft was serious and potentially fatal.

It was possible to find a quack with a miraculous panacea at the fair; or, in towns, to visit an apothecary or surgeon, who had received practical training. Surgery was generally regarded as an inferior craft, best left to artisans. Drugs such as opium, its derivative laudanum, mandrake and other narcotics were given as pain-killers, but they were themselves dangerous and surgery was limited in scope.

Most hospitals had been closed with the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Only a few, such as St. Bartholomew’s, survived. Even serious diseases were treated at home, and recovery depended as much on careful nursing as anything else. A household book must have been a vital resource in trouble. Undoubtedly though, many of the receipts did come from physicians in the first place, though the compilers did not question the underlying ideas.

Nevertheless these ideas had had a long and interesting history.

HIPPOCRATES AND GALEN

Doctors’ treatments, often claimed to be ‘approved’ or with the Latin equivalent Probatum est were used because they always had been. Right up to the seventeenth century, and even beyond, orthodox medicine lay on foundations of Hippocratic and Galenic theory.

Hippocrates of Cos was a legendary Greek doctor (c. 460–370 BC). In fact, about sixty different treatises make up the Hippocratic Corpus, gathered together in Alexandria in about 250 BC.2 The normal state of a stable body was health. Disease resulted from a disruption of equilibrium. Various humours, or physical fluids, were constantly ebbing and flowing through the human system, and the aim of the doctor was to correct any imbalance. Galen later perfected and codified this theory.

Hippocratic medicine was holistic, full of common sense. It laid stress on leading a healthy life, rather than on battling against disease. Diet, exercise, sleep, bathing, and sex ought to be regulated according to one’s temperament, stage of life, and the season. Geographical location was important – marshy areas were known to be unhealthy for example. Bad air was dangerous. Disease had natural causes, and was not inflicted by the gods. If changes in lifestyle didn’t help, medicine might be given. Surgery was a last resort, and too dangerous for a physician to attempt. It was left to specialist craftsmen. Part of the Hippocratic Oath, which dates from somewhere between the fifth and third centuries BC,3 says ‘I will not cut, even for the stone, but I will leave such procedures to the practitioners of that craft.’ The demarcation between physicians and surgeons was to persist up to modern times.

In contrast with the shadowy Hippocrates, Galen of Pergamon (129–216 AD), was a solid historical figure, though later regarded as almost superhuman. He was a well-educated and privileged Greek, the son of an architect. It was said that his father had a dream sent by the healing god Aesclepius, who gave instructions that the boy should become a doctor. Accordingly Galen studied at the best institutions of the time, and in 157 became a physician to gladiators in Pergamon. His experience of wounds, and hence physiology, was invaluable, and after a few years he went to Rome, to treat the wealthy there. He eventually became physician to several Roman Emperors. He was a philosopher as well as a doctor, carried out dissections on animals, and wrote extensively, with passion and logic. He promoted himself as perfecting the work started by Hippocrates. In fact his writings were so brilliant that they remained the best medical knowledge for more than a thousand years. He was so much respected that questioning his conclusions was a kind of heresy, and this held back progress as we define it. If a fact did not fit into Galen’s system, it was assumed to be a false observation, or perhaps humanity had degenerated since his time. In Europe, bodies of executed criminals were used for rare dissections, so it was easy to suggest that they were abnormal anyway.

This was to change slowly during the Renaissance, but at first efforts to improve medicine aimed at correcting corrupt classical texts rather than testing theories in practice.

ANGLO-SAXON MEDICINE

During the so-called Dark Ages, classical writings were saved and copied in centres of learning such as Bede’s Northumbria. Medical texts came to be written in the Anglo-Saxon vernacular too, the Lacnunga manuscript and the Leechbook of Bald being the most famous.4 (‘Laece’ was simply the Old English word for a healer.) These works represent a side step away from the classics to some extent. Although influenced by them, they contain some remedies based on what looks like practical knowledge recently discovered at that time.

The medicine is mostly herbal, but the remedies are much simpler than the later ones of the household books. There is much overt magic such as the use of charms and incantations. Nevertheless, there is a strong family resemblance to some of the receipts of the household manuscripts of the seventeenth century. Ingredients such as earthworms, several kinds of animal dung, foxes’ grease and so on are common to both, and some in fact can be traced back to Pliny, Dioscorides and other classical authorities. It might be surmised that some of these old remedies persisted in folk culture through the Middle Ages, and fragments resurfaced into the manuscript household books.

Theories of disease differed from those of Galen. The body might be attacked from the outside by ‘flying venom’ for example, which caused epidemics, or by the magical elf-shot which brought sickness to animals, as well as complaints such as rheumatism to human beings. A worm might introduce poison and simultaneously remove vitality. ‘Unhealth’ was something which could be removed, perhaps by emetics. Ointments were applied to seal the body against external attacks and to preserve the positive health within it.5

MEDIEVAL (AND LATER) MEDICINE

During the early Middle Ages, medical care had largely been in the jurisdiction of the Church. Healing the sick was a part of its ministry. But there was an obligation on those in Holy Orders not to shed blood, so such men could not offer a complete medical package which included venesection. A lay technician was needed for routine bleeding. Surgery was not a high-status occupation. Increasingly there were lay physicians too, educated at the nascent faculties of medicine in Universities, such as Solerno. This one was particularly well-known to ordinary people because of its compilation of rules for health in the thirteenth century, Regimen Sanitatis Salerni. There were many translations,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Schulbuch / Wörterbuch ► Lexikon / Chroniken |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte | |

| Studium ► Querschnittsbereiche ► Geschichte / Ethik der Medizin | |

| Schlagworte | 17th century • afflictions • Beauty • beauty treatments • Charles I • cleaned his teeth • Cosmetics • Cromwell • Cure • cures • Headache • Health • health & beauty • health and beauty • herbs|oils. foods • history of medicine • kidney stones • King Charles I • Medical History • Medicine • medicine cabinet • Medicines • moisturiser • Oliver Cromwell • Samuel Pepys • secrets of the 17th century medicine cabinet • seventeenth century • Sexually Transmitted Diseases • Shakespeare • SOAP • stuart medicine • stuart medicine cabinet • Teeth • toothpaste • Treatment • Treatments • Venereal Disease • warts • William Shakespeare |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-812-1 / 1803998121 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-812-1 / 9781803998121 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 913 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich