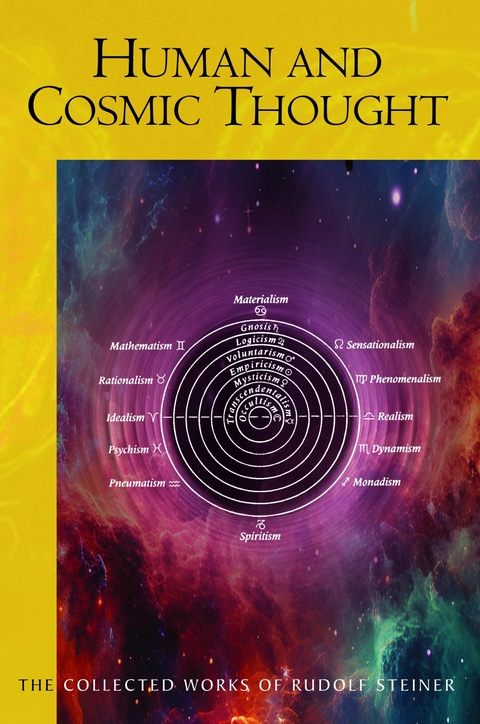

Human and Cosmic Thought (eBook)

152 Seiten

Rudolf Steiner Press (Verlag)

978-1-85584-650-0 (ISBN)

LECTURE 1

BERLIN, 20 JANUARY 1914

IN these four lectures that I am giving in the course of our General Meeting, I would like to speak from a particular standpoint about the connection between the human being and the cosmos. I will first indicate what this standpoint is.

Humans experience within themselves what we may call thoughts, and in thought they can feel themselves directly active, as someone that can survey their own activity. When we observe anything external, for example a rose or a stone, and picture this outer thing to ourselves, someone might rightly say: ‘You can never actually know how much of the stone or the rose you have really apprehended when you represent it. You see the rose, its external red colour, its form, and how it is divided into single petals; you see the stone with its colour, with its several corners, but you must always say to yourself: Hidden within it there may be something else that does not appear to you externally. You do not know how much of the rose or of the stone your representation of it actually embraces.’

But when someone has a thought, then it is they themselves who make the thought. We might say that we are within every fibre of our thought. Thus we are a participant in our activity for the whole thought. We know: ‘Everything that is in the thought I have thought into it, and what I have not thought into it cannot be within it. I survey the thought. Nobody can maintain, when I represent a thought, that there may still be something more in the thought, as there may be in the rose and in the stone, for I have myself engendered the thought and am present in it, and so I know what is in it.’

In truth, thought is most completely our possession. If we can find the relation of thought to the cosmos, to the universe, we shall find the relation to the cosmos of what is most completely ours. This can assure us that we have here a fruitful standpoint from which to observe the relation between ourselves and the universe. We will therefore embark on this course; it will lead us to significant heights of anthroposophical observation.

In the present lecture, however, we shall have to prepare a groundwork that may perhaps appear to many of you as somewhat abstract. But later on we shall see that we need this groundwork, and that without it, we could approach only with a certain superficiality the high goals we shall be striving to attain. Thus we can start from the conviction that when we hold onto that which we possess in our thought, we can find an intimate relation of our being to the universe, the cosmos.

But in starting from this point of view, we encounter a difficulty, a great difficulty—not for our reflection, but for the objective facts. For it is indeed true that we live within every fibre of our thought, and therefore must be able to know our thought more intimately than we can know any representation, but—yes—most people have no thoughts! And as a rule this is not fundamentally realized, for the simple reason that one must have thoughts in order to realize it! What hinders people in the widest circles from having thoughts is that for the ordinary requirements of life, they have no need to go so far as to think; they can get along quite well with words. Most of what we call ‘thinking’ in ordinary life is merely a flow of words: people think in words much more often than is generally supposed. Many people, when they demand an explanation of something, are satisfied if your reply includes some word with a familiar ring, reminding them of this or that. They take the feeling of familiarity for an explanation, and they then fancy they have grasped the thought.

Indeed, this very tendency led at a certain time in the evolution of intellectual life to an outlook that is still shared by many persons who call themselves ‘thinkers’. For the new edition of my Views of the World and of Life in the Nineteenth Century,1 I tried to rearrange the book quite thoroughly, first by prefacing it with an account of the evolution of Western thought from the sixth century BCE up to the nineteenth century CE, and then by adding to the original conclusion a description of spiritual life in terms of thinking up to our own day. The content of the book has also been rearranged in many ways, for I have tried to show how thought as we know it really appeared first in a certain specific period. One might say that it first appeared in the sixth or eighth century BCE. Before then, the human soul did not at all experience what can be called ‘thought’ in the true sense of the word. What did human souls experience previously? They experienced pictures; all their experience of the external world took the form of pictures. I have often spoken of this from certain points of view. This experience of pictures is the last phase of the old clairvoyant consciousness. After that, for the human soul, the ‘picture’ passes over into ‘thought’.

My intention in this book was to bring out this finding of anthro-posophy purely by tracing the course of philosophic evolution. Strictly on this basis, it is shown that thought was born in ancient Greece, and that as a human experience it sprang from the old way of perceiving the external world in pictures. I then tried to show how thought evolves further in Socrates,2 Plato, and Aristotle3; how it takes certain definite forms; how it develops further; and then how, in the Middle Ages, it leads to something that I will now mention.

The development of thought leads to a stage of doubting the existence of what are called ‘universals’, general concepts, and thus to so-called nominalism,4 the view that universals can be no more than ‘names’, nothing but words. Thus there was for this general thought even a philosophical viewpoint, and this view is still widely held today, that general thoughts can be nothing but words.

In order to make this clear, let us take a general concept that is easily observable, the concept ‘triangle’. Now anyone still in the grip of the nominalism of the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries will say somewhat as follows: ‘Draw me a triangle!’ Good! I will draw a triangle for them:

‘Right!,’ they say, ‘that is quite a specific triangle with three acute angles. But I will draw you another.’ And he draws a right-angled triangle, and another with an obtuse angle.

Well, we now have an acute-angled triangle, a right-angled triangle, and an obtuse-angled triangle. Then says the person in question: ‘I believe you: there is an acute-angled triangle, a right-angled triangle, and an obtuse-angled triangle. But they are not the triangle. The collective or general triangle must contain everything that a triangle can contain. The first, second, and third triangles must be subsumed beneath the general concept “triangle”. But a triangle that is acute-angled cannot be at the same time right-angled and obtuse-angled. A triangle that is acute is a special case, not a general triangle; a right-angled and an obtuse-angled triangle are likewise something special. But there cannot be a general triangle. “General” is an expression that includes the specific triangles, but a general concept of the triangle does not exist. It is a word that embraces the single details.’

Naturally, this goes further. Let us suppose that someone says the word ‘lion’. Anyone who takes a stand on the basis of nominalism may say: ‘In the Berlin Zoo there is a lion; in the Hanover Zoo there is also a lion; in the Munich Zoo there is still another. There are these single lions, but there is no general lion connected with the lions in Berlin, Hanover, and Munich; that is a mere word that embraces the single lions.’ There are only separate things; and beyond the separate things—so says the nominalist—we have nothing but words that comprise the separate things.

As I have said, this view has emerged, and is still held today by many sharp logicians. And anyone who tries to explain all this will really have to admit: ‘There is something strange about it; without going further in some way, I cannot make out whether there really is or is not this “lion-in-general” and the “triangle-in-general”. I find it far from clear.’ And now suppose someone came along and said: ‘Look here, my dear chap, I cannot let you off with just showing me the Berlin or Hanover or Munich lion. If you declare that there is a lion-in-general, then you must take me somewhere that it exists. If you show me only the Berlin, Hanover, or Munich lion, you have not proved to me that a “lion-in-general” exists.’ If someone were to come along who held this view, and if you had to show them the ‘lion-in-general’, you would be in difficulty. It is not so easy to say where you would have to take him.

We will not go on just yet to what we can learn from anthroposophy; that will come in time. For the moment, we will remain at the point which can be reached by thinking only, and we shall have to say to ourselves: ‘On this ground, we cannot manage to lead any sceptic to the “lion-in-general”. It really can’t be done.’ Here we meet with one of the difficulties that we simply have to admit. For if we refuse to recognize this difficulty in the domain of ordinary thought, we shall not admit the difficulty of human cognition in general.

Let us keep to the triangle, for it makes no difference to the thingin-general whether we clarify the question by means of the triangle, the lion,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Einführung | R. McDermott |

| Übersetzer | C. Davy, F. Amrine |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-85584-650-0 / 1855846500 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-85584-650-0 / 9781855846500 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich