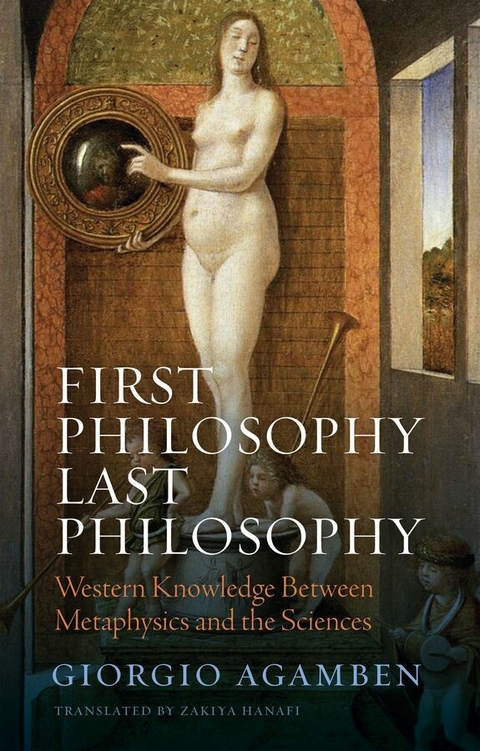

First Philosophy Last Philosophy (eBook)

143 Seiten

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6053-0 (ISBN)

What is at stake in that form of inquiry that the western philosophical tradition has called 'first philosophy' or 'metaphysics'? Is it an abstract, now outmoded branch of philosophy, or does it address a problem that is still of great interest - namely the unity of western knowledge?

In fact, metaphysics is 'first' only in relation to the other two sciences that Aristotle called 'theoretical': the study of nature (phusik?) and mathematics. It is the strategic sense of this 'primacy' that needs to be examined, because what is at issue here is nothing less than the relationship - of domination or subservience, conflict or harmony - between philosophy and science. The hypothesis of this book is that philosophy's attempt to use metaphysics as a way of securing primacy among the sciences has resulted instead in its subservience: philosophy, once handmaiden to theology (ancilla theologiae), has now become more or less consciously handmaiden to the sciences (ancilla scientiarum). So it is all the more urgent to explore the nature and limits of this primacy and subservience, which is what the present book does through an archaeological investigation of metaphysics.

This important rereading of the western philosophical tradition by a leading thinker will be of interest to students and scholars in philosophy, critical theory and the humanities more generally, and to anyone interested in contemporary philosophy and European thought.

Giorgio Agamben is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Venice.

Zakiya Hanafi is an independent scholar based in Seattle, Washington.

Giorgio Agamben is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Venice. Zakiya Hanafi is an independent scholar based in Seattle, Washington.

Translator's Note

1. Second Philosophy

2. Philosophy Divided

3. Critique of the Transcendental

4. The Infinite Name

5. The Transcendental Object = X

6. The Metaphysical Animal

References

Notes

1

Second Philosophy

1. This study investigates what the western philosophical tradition has intended by the expression “first philosophy,” which this same tradition, or at least a large part of it, has also called by the name of “metaphysics.” My interest here is not so much to set out a theoretical definition as to understand the strategic role this concept has played in the history of philosophy. My hypothesis is that the possibility or impossibility of a first philosophy (or metaphysics) determines the fate of every practical philosophy – in the sense, for example, that the impossibility of a first philosophy since Kant is said to define the status of modern thought1 and, conversely, that the possibility of a metaphysics is said to define the status of classical philosophy up to Kant. Even if what “first philosophy” designates turns out to have no object in the end and the primordiality it claims proves to be entirely baseless, this would not make its function any less crucial: because at stake is nothing less than the definition – in the strict sense of setting boundaries – of philosophy in relation to other forms of knowledge and vice versa. In this sense, first philosophy is in truth a second or last philosophy, which presupposes and accompanies the knowledge that belongs to other disciplines, particularly the physical and mathematical sciences. At issue in first philosophy, then – such is my further hypothesis – is the relationship of domination or subservience, and possibly conflict, between philosophy and science in western culture.

As for the term “metaphysics,” Luc Brisson has shown that, although historians of philosophy use it as if it named a field already established at the beginning of western philosophy, in no way does the word appear in classical Greek. Starting from Nicholas of Damascus (first half of the first century CE), the expression ta meta ta phusika begins to appear, but only to designate Aristotle’s treatises. Paul Moraux has demonstrated, however, that the traditionally held meaning of “writings that follow those on physics” is inaccurate: on the list of works by Aristotle that he reconstructs, physics is followed instead by mathematics. Starting with Aristotle’s ancient commentators, then, the title ta meta ta phusika also defines the particular dignity of the science (first philosophy) that deals with forms that exist separately from matter (“But as much of [this science] as is concerned with forms entirely separated from matter, and with the pure activity of the actual intellect, this they [the Peripatetics] call ‘theological’ and ‘first philosophy’ and ‘metaphysics’, as referring to what is found beyond physical realities”2) and comes after physics in the order of knowledge (“The science sought and presented here is wisdom or theology, to which he [Aristotle] also gives the title ta meta ta phusika, because, from our point of view, it comes in order after physics”3). In any case, the syntagm is certainly not Aristotle’s. In two passages (On the Heavens, 277b10 and Movement of Animals 700b7) he seems to use instead the title ta peri tēs prōtēs philosophias (“about first philosophy” or “about first principles”), presumably in reference to the theological treatise of Book Λ (Lambda = 12). The term “metaphysics,” which we use to refer to a work by Aristotle as well as to the illustrious form of philosophy, derives from the medieval Latin traditions of Aristotle’s treatise and is therefore relatively late. From scholasticism on, “metaphysics” tends to overlap with the syntagm “first philosophy,” and it is significant that, in a letter written to Mersenne in December 1640, Descartes refers to his Meditations on First Philosophy as “my Metaphysics.”

2. Because “first philosophy” (prōtē philosophia) appears in Aristotle seven times,4 an examination of the relevant passages is a necessary premise to any interpretation of the concept.

It has been noted that, at the points where first philosophy appears in the Metaphysics, the demarcating function it performs vis-à-vis the other theoretical sciences – the physical sciences and mathematics – is particularly evident.5 In Book Ε (Epsilon = 6), Aristotle begins by distinguishing, among the theoretical sciences, physics and mathematics, which together “mark off” (perigrapsamenai) “a certain being and a certain genus” (on ti kai genos ti) and do not deal “with being simply or with being qua being or with the what-it-is” (peri ontos haplōs oude hēi on oude tou ti estin) (1025b9–10). “That physics is a theoretical [theōrētikē] [science],” he continues, “is plain from these considerations. Mathematics is also theoretical; but whether it deals with things that are immovable and separable [akinētōn kai chōristōn] from matter is not at present clear, although it studies some mathēmata insofar as they are immovable and separable. But if there is something that is eternal and immovable and separable, it is clear that knowledge of it belongs to a theoretical science – not, however, to physics (for physics deals with movable things) nor to mathematics, but to a science prior [proteras] to both. For physics deals with things that are separable from matter but not immovable, and some parts of mathematics deal with things that are immovable and inseparable, but embodied in matter; while the first [science] deals with things that are both separable and immovable. Now all causes [panta ta aitia] must be eternal, but especially these. For they are the causes of the divine things that are manifest [tois phanerois]. There must, then, be three theoretical philosophies [philosophiai theōrētikai], mathematics, physics, and theology [theologikē], since it is quite obvious indeed that if the divine exists anywhere, it exists in a nature of this sort. And the most honorable [timiōtatēn] philosophy must be concerned with the most honorable genus. The theoretical sciences must be preferred to the other sciences, and this to the other theoretical sciences. One might raise the question whether first philosophy is universal [katholou] or deals with a certain genus or one certain nature; for not even the mathematical sciences are all alike in this respect, since geometry and astronomy deal with a certain nature, while universal mathematics applies alike to all. If there is no other existence [tis hetera ousia] along with those composed by nature, physics would be the first science [prōtē epistēmē]; but if there is an immovable existence, this is prior [protera] and the philosophy will be first [prōtē] and universal in this way, because it is first. And it will contemplate being qua being, both the what-it-is and that which inheres in it qua being.” (1026a7–33)

A glancing examination of how the text is structured and the way the argumentation unfolds shows that first philosophy is always mentioned in relation to some limitation of the other two “theoretical philosophies,” especially physics or natural science [phusikē], which without first philosophy “would be the primary science.” From the beginning, as has been suggested, what is in question is not the definition of first philosophy as much as a “strategy of secondarization” of physics.6 As Aristotle points out on two occasions, philosophy is not primary (prōtē), it is simply prior (protera): it is defined not absolutely but comparatively (protera is a comparative formed on pro).

This also holds for the definition (or rather lack of definition) of first philosophy’s object, which is invariably found in relation to those of physics and mathematics, almost as if the regionalization of being (“a certain being and a certain genus,” on ti kai genos ti) it implies were to result from subtraction from or complication of a generic being, characterized as simple (haplōs, without folds). As a definition of first philosophy’s object, the formula “being qua being” (on hēi on) would be vacuous and generic, were it not contrasted with the ti of physics. Even when the qualifiers “immovable and separable” are used to specify the object, they acquire their meaning through opposition to “movable and separable” and “immovable and inseparable,” which define the objects of the other two sciences. And it is significant that the reality of an immovable existence is expressed hypothetically (ei d’esti tis ousia akinētos, “if there is some immovable existence”). The further qualification of the object as “divine” in this text seems so inconsistent with the initial reference to “being qua being” that Natorp and Jaeger came to the rash conclusion that the definition of first philosophy in Aristotle is twofold and contradictory, because it claims to bundle ontology (being qua being) together with...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Zakiya Hanafi |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Schlagworte | Aristotle • Continental Philosophy • Existence • first philosophy • History of Philosophy • Knowledge • Kontinentalphilosophie • Linguistics • Maths • Metaphysics • Metaphysik • Natural science • Ontology • Philosophie • Philosophy • Physics • Plato • Sciences • Theology • Transcendental • Western Philosophy • wisdom |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6053-X / 150956053X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6053-0 / 9781509560530 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 285 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich