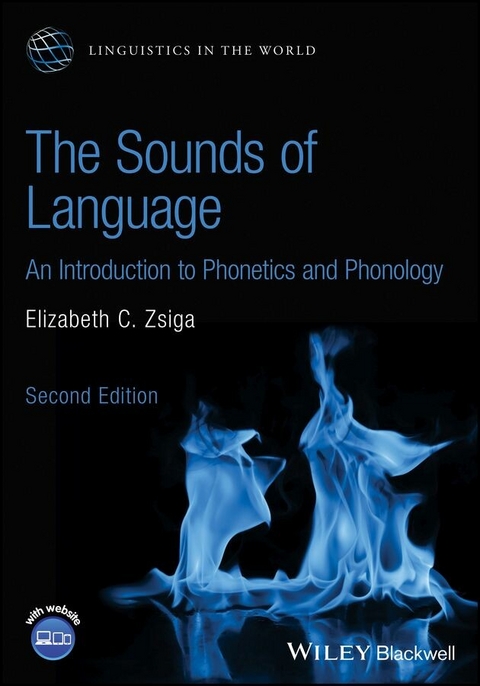

Sounds of Language (eBook)

640 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-119-87850-6 (ISBN)

The fully updated, new edition of the bestselling introduction to phonetics and phonology

The Sounds of Language presents a comprehensive introduction to both the physical and cognitive aspects of speech sounds. Assuming no prior knowledge of phonetics or phonology, this student-friendly textbook clearly explains fundamental concepts and theories, describes key phonetic and phonological phenomena, explores the history and intersection of the two fields, offers practical advice on collecting and reading data, and more.

Twenty-four concise chapters, written in non-technical language, are organized into six sections that each focus on a particular sub-discipline: Articulatory Phonetics, Acoustic Phonetics, Segmental Phonology, Suprasegmental Phonology, the Phonology/Morphology Interface, and Variation and Change. The book's flexible modular approach allows instructors to easily choose, re-order, combine, or skip sections to meet the needs of one- and two-semester courses of varying levels. Now in its second edition, The Sounds of Language contains updated references, new problem sets, new examples, and links to new online material. The new edition features new chapters on Lexical Phonology; Word Structure and Sound Structure; and Variation, Probability, and Phonological Theory. Chapters on Sociolinguistic Variation, Child Language Acquisition, and Adult Language Learning have also been extensively updated and revised.

Offering uniquely broad and balanced coverage of the theory and practice of two major branches of linguistics, The Sounds of Language:

- Covers a wide range of topics in phonetics and phonology, from the anatomy of the vocal tract to the cognitive processes behind the comprehension of speech sounds

- Features critical reviews of different approaches that have been used to address phonetics and phonology problems

- Integrates data on sociolinguistic variation, first language acquisition, and second language learning

- Surveys key phonological theories, common phonological processes, and computational techniques for speech analysis

- Contains numerous exercises and progressively challenging problem sets that allow students to practice data analysis and hypothesis testing

- Includes access to a companion website with additional exercises, sound files, and other supporting resources

The Sounds of Language: An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology, Second Edition, remains the ideal textbook for undergraduate and beginning graduate classes on phonology and phonetics, as well as related courses in linguistics, applied linguistics, speech science, language acquisition, and cognitive science programs.

ELIZABETH C. ZSIGA is Professor of Linguistics at Georgetown University, where she has taught undergraduate and graduate students since 1994. Her research focuses on the sound systems of diverse languages and the intersections between phonetics and phonology. She is the author of The Phonology/Phonetics Interface and has published widely in leading scholarly journals.

The fully updated, new edition of the bestselling introduction to phonetics and phonology The Sounds of Language presents a comprehensive introduction to both the physical and cognitive aspects of speech sounds. Assuming no prior knowledge of phonetics or phonology, this student-friendly textbook clearly explains fundamental concepts and theories, describes key phonetic and phonological phenomena, explores the history and intersection of the two fields, offers practical advice on collecting and reading data, and more. Twenty-four concise chapters, written in non-technical language, are organized into six sections that each focus on a particular sub-discipline: Articulatory Phonetics, Acoustic Phonetics, Segmental Phonology, Suprasegmental Phonology, the Phonology/Morphology Interface, and Variation and Change. The book's flexible modular approach allows instructors to easily choose, re-order, combine, or skip sections to meet the needs of one- and two-semester courses of varying levels. Now in its second edition, The Sounds of Language contains updated references, new problem sets, new examples, and links to new online material. The new edition features new chapters on Lexical Phonology; Word Structure and Sound Structure; and Variation, Probability, and Phonological Theory. Chapters on Sociolinguistic Variation, Child Language Acquisition, and Adult Language Learning have also been extensively updated and revised. Offering uniquely broad and balanced coverage of the theory and practice of two major branches of linguistics, The Sounds of Language: Covers a wide range of topics in phonetics and phonology, from the anatomy of the vocal tract to the cognitive processes behind the comprehension of speech sounds Features critical reviews of different approaches that have been used to address phonetics and phonology problems Integrates data on sociolinguistic variation, first language acquisition, and second language learning Surveys key phonological theories, common phonological processes, and computational techniques for speech analysis Contains numerous exercises and progressively challenging problem sets that allow students to practice data analysis and hypothesis testing Includes access to a companion website with additional exercises, sound files, and other supporting resources The Sounds of Language: An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology, Second Edition, remains the ideal textbook for undergraduate and beginning graduate classes on phonology and phonetics, as well as related courses in linguistics, applied linguistics, speech science, language acquisition, and cognitive science programs.

In all things of nature there is something of the marvelous.

Aristotle, Parts of Animals

Parts is parts.

Wendy’s commercial

Chapter outline

- 1.1 Seeing the Vocal Tract: Tools for Speech Research

- 1.2 The Parts of the Vocal Tract

- Chapter Summary

- Further Reading

- Review Exercises

- Further Analysis and Discussion

- Further Research

- Go online

- References

We begin our study of the sounds of speech by surveying the parts of the body used to make speech sounds: the vocal tract. An understanding of how these parts fit and act together, the topic of Section 1.2, is crucial for everything that comes later in the book. Before we dive into the study of human anatomy, however, Section 1.1 considers some of the tools that speech scientists have used or currently use to do their work: How can we “see” inside the body to know what our vocal tracts are doing?

1.1 Seeing the Vocal Tract: Tools for Speech Research

The vocal tract is composed of all the parts of the body that are used in the creation of speech sounds, from the abdominal muscles that contract to push air out of the lungs, to the lips and nostrils from which the sound emerges. We sometimes call this collection of parts “the organs of speech,” but there really is no such thing. Every body part that is used for speech has some other biological function – the lungs for breathing, the tongue and teeth for eating, the larynx to close off the lungs and keep the two systems separate – and is only secondarily adapted for speech.

We’re not sure at what point in time the human vocal tract developed its present form, making speech as we know it possible; some scientists estimate it may have been 50,000 –100,000 years ago. And we don’t know which came first, the development of a complex brain that enables linguistic encoding, or the development of the vocal structures to realize the code in sound. While hominid fossils provide some clues about brain size and head shape, neither brains nor tongues are well preserved in the fossil record. We do know that no other animal has the biological structure needed to make the full range of human speech sounds. Even apes and chimpanzees, whose anatomy is generally similar to ours, have jaws and skulls of very different shape from ours, and could only manage one or two consonants and vowels. That’s why scientists who try to teach language to chimps or apes use manual sign language instead: chimps are much better at copying human hand shapes than human vocal tract shapes. There are birds that are excellent mimics of human speech sounds, but their “talking” is really a complex whistling, bearing little resemblance to the way that humans create speech. (The exact mechanism used by these birds is discussed in Chapter 9.)

But probably for as long as people have been talking, people have been interested in describing how speech sounds get made. Linguistic descriptions are found among the oldest records of civilization. In Ancient India, as early as 500 BCE, scribes (the most famous of whom was known as Pāṇini) were making careful notes of the exact articulatory configurations required to pronounce the Vedic Scriptures, and creating detailed anatomical descriptions and rules for Sanskrit pronunciation and grammar. (The younger generation, apparently, was getting the pronunciation all wrong.) Arab phoneticians, working centuries later but with many of the same motivations as the Indian Grammarians, produced extensive descriptions of Classical Arabic. Al-Khalil, working in Basra around 750 CE, produced a 4000-page dictionary entitled Kitab al ‘ayn, “The Book of the Letter ‘Ayn’.” The ancient Greeks and Romans seemed to be more interested in syntax and logic than in phonetics or phonology, but they also conducted anatomical experiments, engaging in an ongoing debate over the origin of speech in the body. Zeno the Stoic argued that speech must come from the heart, which he understood to be the source of reason and emotion, while Aristotle deduced the sound-producing function of the larynx. The Greek physician Galen seems to have settled the argument in favor of the Aristotelian view by noting that pigs stop squealing when their throats are cut. Medieval European linguists continued in the Greek tradition, further developing Greek ideas on logic and grammar, as well as continuing to study anatomy through dissection.

The main obstacle in studying speech is that the object of study is for the most part invisible. Absent modern tools, studies of speech production had to be based on either introspection or dissection. (According to one history of speech science (Stemple et al. 2000), it didn’t occur to anyone until 1854 that one could use mirrors to view the living larynx in motion.) Of course some speech movements are visible, especially the lips and jaw and sometimes the front of the tongue, so that “lip reading” is possible, though difficult. But most of speech cannot be seen: the movement of the tongue in the throat, the opening of the passage between nose and mouth, sound waves as they travel through the air, the vibration of the fluid in the inner ear. The experimental techniques of modern speech science almost all involve ways of making these invisible movements visible, and thus measurable.

One obvious way is to take the pieces out, at autopsy. Dissection studies have been done since antiquity, and much important information has been gained this way, such as our knowledge of where muscles and cartilages are located, and how they attach to each other. But the dead patient doesn’t speak. Autopsy can tell us about the anatomy of the vocal tract, that is, the shape and structure of its parts, but it cannot tell us much about physiology, that is, the way the parts work together to produce a specific sound or sound sequence.

The discovery of the X-ray in 1895 was a major advance in speech science, enabling researchers to “see” inside the body. (The mysterious “X” ray was discovered by physicist Wilheim Conrad Röntgen, who received the first Nobel Prize in physics for his work.) X-rays are not necessarily great tools for visualizing the organs of speech, however, for two reasons. X-rays work because they pass through less dense, water-based soft tissue like skin, but are absorbed by denser materials like bone, teeth, and lead. Thus, if an X-ray is passed through the body, the bones cast a white “shadow” on a photographic film placed behind the subject. The first problem with the use of X-rays in speech science is that muscles, like the tongue, are more like skin than like bones. The tongue is visible on an X-ray, but only as a faint cloud, not a definite sharp outline.

Figure 1.1 shows the results of one experiment where researchers tried to get around this problem in an ingenious way. These images were made by the British phonetician Daniel Jones, in 1917. Jones was very interested in vowel sounds, and is famous (among other achievements) for devising a system for describing the sound of any vowel in any language (the “cardinal vowel” system, which is discussed in Chapter 4). But nobody really knew exactly how the tongue moved to make these different sounds, since we cannot see most of the tongue, and we do not have a very good sense of even where our own tongues are as we speak.

Figure 1.1 X-rays from the lab of Daniel Jones. Source: Daniel Jones 1966/Cambridge University Press.

To create these images, Jones swallowed one end of a small lead chain, holding on to the other end, so that the chain lay across his tongue. He then allowed himself to be X-rayed while articulating different vowel sounds, and these pictures are the result. The images, beginning at the upper left and going clockwise, show vowels similar to those in the words “heed,” “who’d,” “hod,” and “had.” (“Hod” rhymes with “rod,” and was a common word in 1917. It refers to a bucket or shovel for carrying coal.) The tongue itself does not image well, but the lead chain shows up beautifully, indicating how the tongue is higher and more toward the front of the mouth for the vowel in “heed” than the vowel in “hod.” (The large dot showing the high point of the tongue was drawn in by hand, and the other black dots are lead fillings in the subject’s teeth.)

The second problem with X-ray technology, of course, is that we eventually learned that absorbing X-rays into your bones, not to mention swallowing lead, is dangerous for the subject. Prof. Jones’ experiments would never make it past the review committees that every university now has in place to protect participants’ health.

A safe way to get pictures of parts of the vocal tract is through sonography (also known as ultrasound imaging). This technology, based on the reflection of sound waves, was developed in World War II, to allow ships to “see” submarines under the water. Most of us are familiar with this technology as it is used to create images of a fetus in utero. The technology works because sound waves pass harmlessly and easily through materials of different kinds, but bounce back when...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Sprachwissenschaft |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-87850-0 / 1119878500 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-87850-6 / 9781119878506 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 30,9 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich