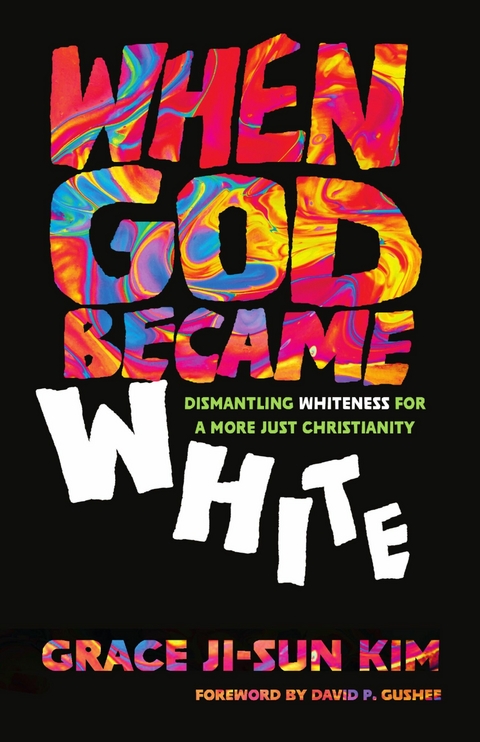

When God Became White (eBook)

200 Seiten

IVP (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0940-6 (ISBN)

Grace Ji-Sun Kim (PhD, St. Michael's College, University of Toronto) is associate professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion. She is author or editor of fifteen books, including Embracing the Other,Christian Doctrines for Global Gender Justice, and Intercultural Ministry. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA).

Grace Ji-Sun Kim (PhD, University of Toronto) is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Indiana. She is the host of the Madang podcast and has published in TIME, Huffington Post, US Catholic, and The Nation. She is an ordained PC(USA) minister and enjoys being a guest preacher on most Sundays. Her many books include Invisible, Reimagining Spirit, and Healing Our Broken Humanity. She and her spouse, Perry, have three young adult children and live in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Introduction

White Christianity

I am going to say something that may sound extreme, but if you stay with me, you’ll understand why it’s true. Everything is connected to race.

Race might be considered a social construct, but we can see how race affects culture, history, religion, employment, laws, and ideas. Race influences how we act and behave daily. It forms our perceptions of each other and affects how we act in different circumstances. The societal views of immigrants, Natives, and refugees have a profound impact on our ability to relate to people of different races. It has also greatly influenced Christianity and our understanding of God.

When I began to realize the enormous impact of race, I knew it was important for me to study race, racism, and ethnicity to understand how we have come to construct a white Christianity and a white God. This is how I began my explorations for writing this book. My own life has been impacted by race relations because it has ultimately defined me, had a negative influence on me daily, and has formed my own understandings of a white Christianity and a white God.

When I was growing up in the 1970s in London, Ontario, we began elementary school each morning by reciting the Lord’s Prayer and singing the national anthem. It was very clear to me as an immigrant child that Canada was a Christian country and that I needed to become a Christian if I was going to fit into my new home. Our family did not have any religious affiliations when we first immigrated in 1975. But a very nice young Korean couple started asking my older sister and me to go to church with them. My sister and I eventually began attending and had a lot of fun at church. We met other Korean kids our age and we made lots of new friends there.

Soon, my parents started attending church with us as other Korean immigrants encouraged them to join us at the local Korean church. They were happy to meet other Korean immigrant families at the church and it became a community for us. We did not know anyone when we moved to Canada, so the church became our extended family. We held birthday parties, weddings, anniversaries, and any other celebrations at church. It was a place for us to become a family with other Korean immigrant families.

Through attending church, our family eventually became Christians. We ended up attending a Korean Presbyterian church on Sundays, but mid-week and on Friday nights, my parents dropped my sister and me off at a white Baptist church and a Christian and Missionary Alliance church for Bible studies, fellowship, and worship. Church soon overtook our lives; everything was planned around church events.

I made lots of friends at these different churches. Part of the purpose for attending so many different churches was that, in a way, it provided free English classes. My parents were worried that our English wasn’t good enough for us to excel at school, and they thought by being immersed in white churches, we would learn to speak better and to understand the white culture we were living in.

I was definitely informed by this experience. The churches all impacted my perception of God, who Jesus was, and what I was supposed to do with my life. When I think about my childhood and how I raised my own three children, I see a world of a difference. One day when I was trying to wake my youngest, who was a teen at the time, I nudged him over and over until he said, “What?!” I told him to hurry up and get ready for church. He complained, “Again?” I said, “What you do you mean again? This is the first time going to church this week.”

If my children understood the number of churches I went to during a week, they would be happy they only had to go to church once a week.

I was an Asian immigrant girl who grew up with a white Jesus. And that wasn’t just at church. We had a white Jesus hanging on the wall in our living room—the extremely popular Head of Christ by artist Warner Sallman. I never found out where my dad got this famous print, but I am certain he didn’t buy it. We were too poor to buy even food and basic clothing, never mind nonessentials like decor. I am sure my dad must have found it someplace near the garbage or some stranger at his factory gave it to him for free.

My mother was a strong woman of faith, and she loved the picture of Jesus and admired it with a huge smile. She felt the best place to hang this print of Jesus surrounded by a cheap, fake wood frame was over our couch so you could see him when you entered the apartment. She thought if you sat on the couch, the “blessing” of Jesus would come down on you. Sallman’s picture of a white Jesus was prominent in our home, and I believed that is how Jesus really looked.

My mother treated this print image as if it were a holy art piece and carefully packed it every time we moved. That image was one of the first things unpacked in the new place. In every place we lived, she hung it behind the living room couch so we could see the image of Jesus every day and any visitors to the home would see it immediately.

The white Jesus on our wall was a depiction to me of how God looked as well. I pictured God as an old white man, just as everyone else did. There was no reason to question that notion. It was everywhere: in paintings, stained-glass windows, and storybooks. I never questioned it. I didn’t even think twice about whether Jesus was white or not. It was not in my consciousness to question anything that was taught by my mother or the church. Both pushed a white Jesus, and I just took it as the truth.

I have no idea where my mother’s beloved white Jesus picture is now. It is probably in a dump somewhere. My sister threw out many of our belongings every time we moved homes. But the damage is done. It is so difficult to rid ourselves of these deeply embedded images of a white male God that were engrained in us at home, at church, and in society. But, I have now come to see the consequences of believing in a white male God.

What I didn’t know then that I know now is how influential that picture was on my own theology and faith development. That image of a white Jesus was imprinted on my brain and body so that I could not even question whether Jesus actually looked like that. It was a given, as it was the most famous picture of Jesus. I went to visit family in Korea twice during my youth, and even my family members there had the same picture of the white Jesus in their homes. The Korean churches also had the same picture of white Jesus. Furthermore, when I traveled to India during my seminary years, all the churches that I visited had this same white Jesus picture. This confirmed to me that this must be the real Jesus, as it is universally understood to be the image of Christ.

I just took it for granted that Sallman’s Head of Christ must be the real thing. I never questioned it until much later in my adult life. This was also partly due to the reverence that my mom had for the cheap printed copy of the image in our home. She would look at it as if in prayer. To her it was an indication that ours was a Christian home, and this meant the world to her.

My mom was a very conservative evangelical Christian. Though we attended the First London Presbyterian Church, the denomination didn’t mean much to her or our entire family. We were more concerned about preserving our conservative Christianity in any way, shape, or form. She loved this image of a white Jesus, and thus everyone else in the family was expected to love this image too. In Korean culture, you don’t question parents or elders; you just obey. To question the validity of this painting felt bad, as if I were questioning my mother’s beliefs and understandings.

My family’s story is the same as many of my Christian friends. Sallman’s image may not have been as prominently displayed as it was in our house, but it was in their homes to signify that they were Christians. We all lived with this white representation of Jesus.

Living in white spaces as a nonwhite person is exhausting. It is so depleting that it sucks the life out of you. I have experienced racism throughout my life. I have tried to understand racism and how it functions, and I have learned that the only way to fight it is to address whiteness and dismantle it.

After growing up in an environment that reinforced the whiteness of God, not just with the Sallman’s image but also through other biblical and church teachings and practices, it was a devastating revelation that these images of a white Jesus might be wrong and even intentionally created to reinforce white supremacy in Christianity, society, and culture. This book is about the religious journey I took to make sense of my own experiences and place them in context. It explores the emergence of a white Jesus and what the implications of this are on racialized minorities. In this process, I came to understand how whiteness has corrupted our understanding of each other and God. If we are to overcome the devastating effects of whiteness, we need to move forward and adopt a theology of visibility so we can embrace the other and live in peace with our neighbors.

I hope my questions and challenges of a white Christianity will help you in your own explorations of faith, spirituality, and God. Please join me on this inner journey of unpacking whiteness, white Christianity, and a white God.

WHITENESS

For centuries, the classification of race has been a powerful tool for white male lawmakers, leaders, church ministers, and the privileged to maintain their power and the status quo. But how did it start? Why...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | David P. Gushee |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Schlagworte | Christian History • Christianity • Christian theology • Cultural Studies • gender of god • Gender Studies • God • Image of God • Institutional Racism • is god male • is god white • Race • Racism • religion and western culture • Social Justice • Theology • Western Christianity |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0940-4 / 1514009404 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0940-6 / 9781514009406 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich