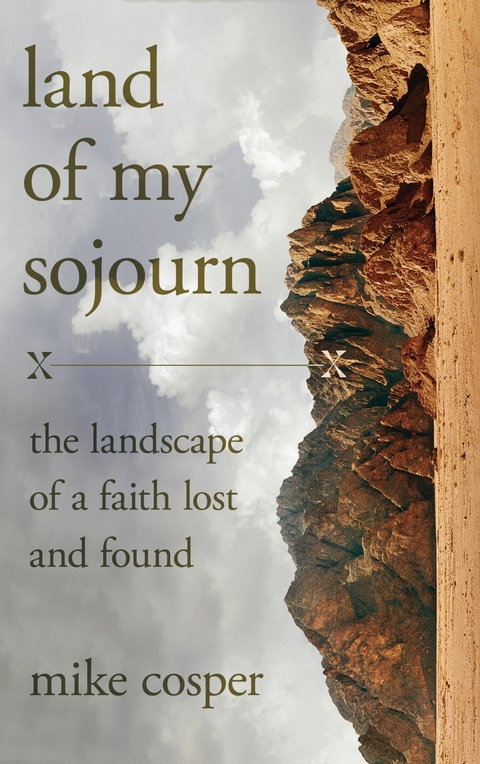

Land of My Sojourn (eBook)

168 Seiten

IVP (Verlag)

978-0-8308-4735-8 (ISBN)

Mike Cosper is the founder of Harbor Media, where he produces podcasts for Christians in a post-Christian world. Prior to that, he served as the executive pastor for worship and arts at Sojourn Church in Louisville, Kentucky. He is the author of The Stories We Tell: How TV and Movies Long for and Echo the Truth and Rhythms of Grace: How the Church's Worship Tells the Story of the Gospel. He lives in Louisville, Kentucky, with his wife, Sarah, and their two daughters.

Mike Cosper is the director of podcasting for Christianity Today, where he hosts The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill and Cultivated. Mike also served as one of the founding pastors at Sojourn Church in Louisville, Kentucky, from which he launched Sojourn Music, a collective of musicians writing songs for the church. He is the author of several books, including Recapturing the Wonder and Rhythms of Grace. He lives in Louisville with his wife and two daughters.

Introduction

When Gravity Fails

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY—FALL 2016

“I’m not sure we can stick with you on this,” Greg said.

We were sitting in a large executive suite on the upper levels of an old, turn-of-the-century building. A wide antique window behind him framed the setting sun, which cut a low band of gold across an otherwise iron-gray sky. I didn’t know Greg well. We’d been introduced earlier that year when I began putting together plans for a new media-focused nonprofit to serve Christians in the marketplace. I’d pitched him the idea and asked him to consider being involved in a couple of ways as we launched. He’d taken it a step further, expressing interest in helping to build certain elements of the ministry with me.

By the time of this meeting we had planned not only to work together on the nonprofit but also to collaborate on equipping resources for Christian leaders inside several companies. Suddenly, he hit the brakes.

“Help me understand,” I said.

He leaned forward, resting his elbows on his knees, wringing his hands, and looking at the floor. “I just think you’ve got this election thing wrong,” he said.

“What do you mean,” I asked. “The Trump thing?” There was a long silence.

Only a few days earlier the now-infamous Access Hollywood tape had leaked, in which then-presidential candidate Donald Trump described how fame allowed him to get away with anything, including grabbing women “by the p____.” In a newsletter I’d written what I thought was a fairly common-sense analysis from a Christian perspective—that he had failed every character test by which other presidents and politicians had been measured. No one put it better than Albert Mohler, at least at the time, when he said that were he to endorse Donald Trump, consistency would demand that he write a letter of apology to Bill Clinton as well for vocally opposing the former president’s sexual misconduct. (Notably, Mohler did endorse Trump in 2020. As of this writing, no such “consistent” apology has come.)

My point in writing the newsletter wasn’t (as William F. Buckley once famously phrased it) to stand athwart history yelling “Stop!” I didn’t presume to stand in front of a steam train on principle. Rather, I thought I was reiterating common-sense ideas in an election cycle in which wild voices from the fringe were being amplified in new and horrible ways. Honestly, I thought I was in the majority on Trump’s character. I was, however, not in the majority.

“Look,” I said, “I understand that for some folks this is a binary decision. I happen to disagree, but I understand.”

“That’s not it,” Greg said. “It’s more . . . important than that.” Weird emphasis. “I just think it’s time for us all to get behind him—Trump. Because, well . . .”

Now Greg sat up. He looked me right in the eye. “Finally, someone is going to stand up for the White man.”

To that point in my life I’d been a pastor working at the intersection of faith and culture. Leading a ministry for artists and church musicians, writing about movies, music, and TV, and teaching about politics, public witness, and faithfulness in the marketplace. No doubt, there were places I parted ways with the Christian conservatives in the generations before me, but these were mostly differences in degree, not in principle, that left plenty of common ground to collaborate on. This meeting, this break, read as something else. Something tectonic. It hit like a thunderclap.

The 2016 election cycle had been weird. The gloves had come off when the Republicans were still debating each other. Mockery and derision set the tone. Trump seemed to only gain momentum the more crass he became. And some pockets of the internet were combining their support of the man with other, unsettling sentiments. But that was the internet. The internet couldn’t be real. Now it was across the table. Someone who was a collaborator ten minutes ago now was a stranger to me. It was disorienting.

In the aftermath I began to wonder if this could be the norm. Had the animating concerns that fell under the banners of “conservatism,” “traditional values,” “religious liberty,” or even “evangelicalism” been a veneer, a lure to co-opt people in the church into the service of ugly, identitarian politics?

To put it a little differently, what had I been giving my life to for the past fifteen years?

I remember seeing Space Camp in the theaters in 1986. It’s an 80’s classic starring Kate Capshaw, Lea Thompson, Tom Skerritt, and Joaquin Phoenix. In it a ragtag group of misfits are grouped for a week of space camp. Due to Promethean mistakes and good old-fashioned hijinks, their team is accidentally launched into space aboard an underequipped space shuttle. High adventure ensues. Lots of learning. Lots of hugging.

One scene has stuck with me for almost forty years. Andie, the kids’ camp counselor, heads out on a spacewalk to collect oxygen tanks to resupply the shuttle. When she can’t quite reach them, Max—the youngest and smallest of the group—is sent out to help. While tugging on a tank, Max loses his grip and goes hurtling into space, untethered to anything at all. That image—tumbling into the vacuum of space, no gravity to bring you back, just an eternal drift into blackness—scared the bejeezus out of six-year-old me. It still does.

Finally, someone is going to stand up for the White man.

With these words a switch flipped. Gravity vanished. I could only watch, stunned, as the ground drifted away beneath me. The year 2016 felt like that 1980s nightmare came to life. It was, for lack of a better word, an apocalypse. A revealing. I found myself in a dark landscape without a tether. Friendships, partnerships, my sense of place in my church and city, the broader evangelical community—none of it held together anymore. This meeting was the beginning of the season that would leave me feeling completely adrift.

In Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, someone asks Mike—a hard-drinking and self-pitying Scottish war veteran—how he went broke. “‘Two ways,’ Mike said. ‘Gradually, then suddenly.’”

I’ve discovered that spiritual disillusionment happens that way too. You crash into this sense that faith as you knew it doesn’t make sense anymore, but when you look backward, you see signs and evidence you didn’t take seriously at the time.

Looking back, the first glint of disillusionment I see happened in 2012, not long after the murder of Trayvon Martin. I preached a sermon from Ephesians 2, where Paul describes how Jesus breaks down the walls of hostility that separate men and women of different races. I took that sermon as an opportunity to speak to the broader racial tensions that were emerging in our country but also as an opportunity to help our church see the unifying beauty of Christ as we moved into a more diverse neighborhood and began to pursue a more multicultural approach to ministry. Similar to the newsletter in 2016, I didn’t think I was saying anything controversial. Rather, I thought I was helping the church find language for taking the next steps with these issues.

In the sermon I took no political stances. I simply preached about compassion and empathy for our Black brothers and sisters, especially those in the neighborhood around our church. I tried to relay their stories—as they had told them to me—of how everyday experiences for Black Americans differed from our majority-White congregation’s. I talked about how fear of being called a racist made many White Christians hypersensitive to discussions of race and invited the community to make space for listening to the experiences and perceptions of Black and Latino members of our church. Maybe, I suggested, some of our assumptions are wrong—especially when they’ve been formed without any input from minority voices. Maybe there was some room for repentance.

This was years before critical race theory would become a political boogeyman, before Black Lives Matter would become a controversial organization, before woke would be co-opted by the political right and used as a pejorative. Nonetheless, saying that Black and White Americans had very different everyday experiences, suggesting that racism was still an issue in America, and reading a few short quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. and Frederick Douglass (along with lots of Scripture) created no small amount of controversy. After preaching, I was harangued in the parking lot and the church received angry calls and emails for several weeks. Some members called for an apology or my removal from the staff.

At the time I didn’t have categories for understanding those reactions. Later, when I wrote several blog posts about race, police shootings, and how White Christians could join their neighbors in compassion and lament, the response grew even more threatening and vitriolic.

In 2012 I tried to be open. I reminded myself that defensive reactions could easily be rooted in fear and shame. An anxious response to the accusation of racism might not be racism itself. Post-2016 all of this started to read differently for me. I still believe anxiety and fear can play a role but only as part of a larger story about deceived and corrupted moral imaginations.

...| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.2.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik |

| Schlagworte | Abuse • christiainity • Christian memoir • Crisis • crisis of faith • Deconstruction • disillusioned • Disillusionment • doubting • doubting faith • evangelical • Israel Pilgrimage • journey • lost in the wilderness • mega church • megachurch pastor • ministry • Narcissism • Pastor • Pilgrimage • rediscover • rethink • rise and fall of mars hill podcast • scandal • scandals in the church • sojourn church • Spiritual |

| ISBN-10 | 0-8308-4735-9 / 0830847359 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-8308-4735-8 / 9780830847358 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich