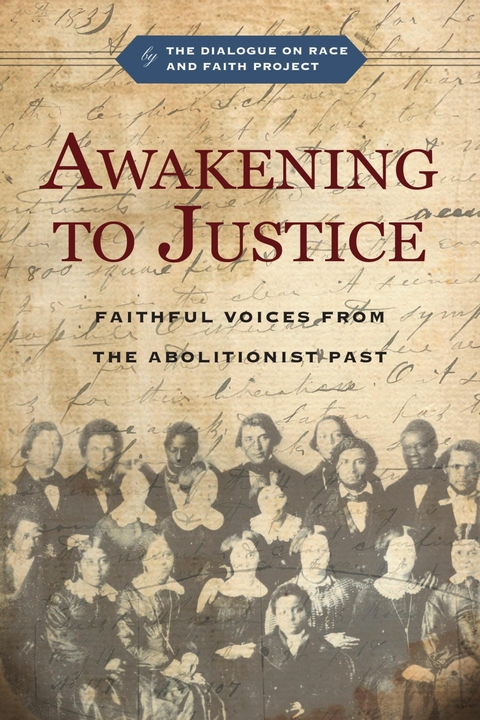

Awakening to Justice (eBook)

240 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0919-2 (ISBN)

The Dialogue on Race and Faith Project brings together a multicultural team of Christian scholars to study a newly discovered abolitionist journal, to meet and travel to sites of importance from the nineteenth-century antislavery movement, and to discuss how issues of faith and race among abolitionists may provide a usable history for addressing the struggle for racial justice today. Project members and contributors include: Jemar Tisby, Christopher P. Momany, Sègbégnon Mathieu Gnonhossou, David D. Daniels III, R. Matthew Sigler, Douglas M. Strong, Diane Leclerc, Esther Chung-Kim, Albert G. Miller, and Estrelda Y. Alexander.

The Dialogue on Race and Faith Project brings together a multicultural team of Christian scholars to study a newly discovered abolitionist journal, to meet and travel to sites of importance from the nineteenth-century antislavery movement, and to discuss how issues of faith and race among abolitionists may provide a usable history for addressing the struggle for racial justice today. Project members and contributors include: Jemar Tisby, Christopher P. Momany, Sègbégnon Mathieu Gnonhossou, David D. Daniels III, R. Matthew Sigler, Douglas M. Strong, Diane Leclerc, Esther Chung-Kim, Albert G. Miller, and Estrelda Y. Alexander.

INTRODUCTION

Waking a Sleeping Church

Douglas M. Strong and Christopher P. Momany

O it seems as if the church were asleep, and Satan has the world following him.

WHAT IF YOU COULD DISCOVER an artifact that would change your life? That’s exactly what happened to Chris Momany in the fall of 2015.

It was an otherwise uneventful workday in late October when Noelle Keller, the archivist at Adrian College in Michigan, received a large box. Staff members in the alumni office had found the dust-filled container high up in a supply closet during a remodeling project and sent it to the library. Opening the box, Keller extracted a miscellaneous hodgepodge of twentieth-century objects haphazardly stuffed inside: yellowed newspaper clippings, headshots of a former college president, assorted photos, even a freshman beanie from the 1950s. But resting at the bottom of the stack, she found something else—an aged notebook with a marbled cover, filled with page after page of handwriting. Keller noted the dates on the pages and made a startling, unexpectedly breathtaking deduction: this item had come from much further in the past.

But what was it? Keller phoned Chris Momany, the college’s chaplain and resident religious historian, to ask whether he could identify the origin of the notebook. Momany instantly recognized the significance of the find. Not waiting for a moment, he rushed over to the library. When he arrived at Keller’s workroom and peered down at the first page of the opened tablet, he saw a date: July 14, 1839. That was twenty years before the establishment of the college. How did they possess a text that predated the institution?

Figure I.1. David Ingraham’s personal journal, 1839–1841, held in the archive of Adrian College, Michigan

Momany puzzled for a moment, and then an idea struck. The Reverend Asa Mahan, a holiness theologian and abolitionist, founded Adrian College in 1859. Could this be one of Mahan’s early notebooks? If so, it would have been a treasure that he brought with him to Michigan from Ohio, where he had previously served as president of Oberlin College. But Momany wasn’t convinced that Mahan really was the source of the discovery. For one, the handwriting in the notebook was too readable, and Mahan had earned a reputation for having incomprehensible scrawl. This script seemed different—almost, well, legible—and the document was organized like a personal diary. So who was the author?

In a moment of recklessness, Momany asked Keller if he could put the artifact in his briefcase and take it home over the weekend. He offered a promise not to drink coffee while searching the notebook for clues and that he would only keep a pencil (not a pen!) close by. Keller consented: after all, the relic had been knocking about in containers or various cabinets for almost two centuries by then.

Figure I.2. Page from David Ingraham’s journal, December 25, 1839, showing his diagram of the slave ship Ulysses

The next day, Momany began to read, handling the old notebook very carefully as he examined its fragile pages. Slowly, very slowly, the author’s identity unfolded before him. The notebook contained references to educational and pastoral work in Jamaica, where emancipation had taken place in 1838, just a year before the starting date of the journal. There’s a well-established link between Oberlin and missions on behalf of recently freed enslaved people.

But about a quarter of the way through the manuscript, Momany’s eyes fell on something unique on a certain page. Unlike all the other pages, which were filled only with handwriting, this one included a drawing of some kind. Momany stared for a moment at the weathered text, then gasped. He was scrutinizing a rough sketch of a ship that had been used to transport enslaved people. On the table in front of him was a bird’s-eye diagram of a Portuguese vessel that the British Royal Navy had impounded for illegally trafficking hundreds of West African men, women, and children.

Through much sleuthing, Momany eventually uncovered the journal’s provenance: it belonged not to Mahan after all, but to David S. Ingraham, a White, Oberlin-educated abolitionist missionary who ministered to emancipated communities in Jamaica. Ingraham had started schools and churches among his congregants on the island, teaching people to read and preaching a message of love for God and humanity.

Ingraham’s diary measures 7 ¾ × 11 inches. It contains about one hundred brown-tinted leaves of faded cursive. The entries begin in the summer of 1839 and end nearly two years later, in March 1841, just four months before the author’s untimely death from lung disease. The artifact, Momany determined, had previously been unknown to scholars, or to anyone, for that matter, before the day it was discovered in a storage closet in 2015.

Ingraham drew his layout sketch of the “slave brig Ulysses” in his journal after having boarded the seized ship at Port Royal, Jamaica. By interviewing the crew of the Navy schooner that intercepted the brig, Ingraham found out that 556 abducted people, before being unshackled by British authorities, had suffered incomprehensible misery and humiliation aboard. In his journal (and later in a letter sent to the editors of several US newspapers, reprinted in this book’s appendix), Ingraham documented the abuse that the West Africans had endured during a fifty-day voyage.

His journal, lost and forgotten for so long, imparts detailed accounts of current events, expressions of devotion to God, profound theological insights, and tender commentary about his family and congregants, all of which are important things for us to recount and interpret for the present day. But Ingraham wrote his most impassioned remarks immediately following his inspection of the ship. “It seems as if the church were asleep,” he lamented. “O where are the sympathies of Christians for the slave and where are their exertions for their liberation? . . . Who can measure the guilt or sound the iniquity of this nefarious traffic?”1

So just who was David Ingraham? And what was it that motivated him to fight for freedom? Ingraham was one of the student “rebels” at Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati who took an unqualified stand against slavery during a historic series of debates in 1834, to the great consternation of seminary administrators, who meted out harsh discipline against students who took that position. The punitive action prompted Ingraham and thirty-one other rebels to leave Lane and transfer to Oberlin, a revivalist abolitionist college farther north in Ohio. Students were not the only ones to leave. Asa Mahan, one of the few Lane trustees to support the students, moved to Oberlin too, as did the famous evangelist Charles G. Finney, who joined the Oberlin faculty. Mahan himself would become Oberlin’s president. Years later, he wrote fondly about Ingraham, referring to him as the “first fruit” of his ministry, a mentorship that may explain how Ingraham’s journal ended up at a college, Adrian, at which Mahan would also become president.2

MORE THAN JUST AN OLD MANUSCRIPT

Historians relish the chance to get their hands on archival material that has been mislaid. But Chris Momany wondered how he should disseminate the information that was contained in the discovery. He reached out to Doug Strong, a fellow historian of Christianity, to share the news and to strategize about what to do. Strong and Momany determined that Ingraham’s faith-filled manuscript merited far more than just a transcription.

The journal’s reappearance coincided with the 2010s’ increased visibility of anti-Black violence in the United States. The gruesome deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and others, as well as hate crimes directed toward Asian Americans, spotlighted the ongoing reality of race-based discrimination at individual and systemic levels. At the time of this writing in the 2020s, Americans of all ethnicities have found themselves navigating through the turbulent waters of an overdue racial reckoning. Christians, whose discipleship demands that they engage in that process of cultural self-examination, also have a particular obligation to provide upcoming generations with clear-eyed historical retrospectives and biblically based ethical guidance. What was taking place in the era in which Ingraham lived, during which he encountered the Ulysses? And what is God calling us to do here and now as practitioners of repentance and agents of justice?

Poring over Ingraham’s nineteenth-century diary, Momany and Strong realized that studying the artifact could be a means through which twenty-first-century Christians might address the reality of racism in society today. Why not allow the journal, the scholars wondered, to be a vehicle for people of various backgrounds to study the past for the sake of the present? Perhaps the stories of David Ingraham and other justice-seeking revivalist abolitionists of his day can inspire contemporary dialogue and activism for racial equity. Was there an abolitionist legacy that bore witness to a hopeful, more faithful tomorrow? A fuller and more nuanced historical narrative may offer relevant resources for reflection and action in faith communities. Could Christian abolitionists of the past provide us with a new history on which to build a new future?

With...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 29 illustrations (13 color) |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Abolition • abolitionist movement • academic • American • American History • Antiracist • Black lives matter • BLM • Christian • Christian abolition • Christian History • Christianity in America • Church • Church history • combat • countercultural • Dialogue • faith and race • History • holiness movement • Injustice • Missionary • Nineteenth century • Power • Race • racial injustice • Racial Justice • Racism • resistance • revivalist • Slavery • Social • Social Justice • True story |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0919-6 / 1514009196 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0919-2 / 9781514009192 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich