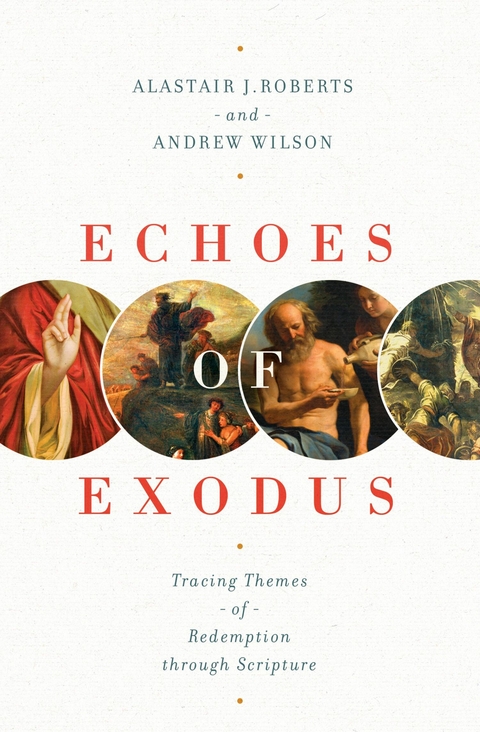

Echoes of Exodus (eBook)

176 Seiten

Crossway (Verlag)

978-1-4335-5801-6 (ISBN)

Alastair J. Roberts (PhD, Durham University) is one of the participants in the Mere Fidelity podcast and a fellow of Scripture and theology with the Greystone Theological Institute.

Alastair J. Roberts (PhD, Durham University) is one of the participants in the Mere Fidelity podcast and a fellow of Scripture and theology with the Greystone Theological Institute. Andrew Wilson (PhD, King's College London) is the teaching pastor at King's Church London and a columnist for Christianity Today. He is the author of several books, including Incomparable; Echoes of Exodus; and God of All Things. Andrew is married to Rachel and they have three children: Zeke, Anna, and Samuel.

1

A Musical Reading of Scripture

Scripture is music.

We use musical metaphors all the time when we talk about the Scriptures, without even thinking about it. We might describe the Bible as a symphony or a love song. We might refer to the opening of Genesis as an overture or to Revelation as a finale. We might talk about the story being composed or perhaps orchestrated by God, with themes and rhythms and echoes running through it, all building to a crescendo. If we are handling some of the difficult sections, we might say that there is a clash here or a discordant note there, but that there is always, ultimately, a harmony within the Word of God, and therefore that we can expect things to resolve. We could describe John as written in a different key than the other three Gospels, or Chronicles as a transposed version of Kings. We might even identify specific books with particular musical modes or styles: Job is the blues, Ecclesiastes is jazz, some of the psalms are in the minor key, or whatever. Much of our language for Scripture is musical.

That might sound trivial. After all, we use figures of speech all the time, and don’t necessarily intend for them to be taken that seriously. But the reality is that metaphors, particularly ones that are applied consistently in a particular context, exercise a powerful influence over the way we conceptualize things, and this influence can be helpful, damaging, or neither. It’s worth thinking about that for a moment.

To start with a fairly neutral example: we tend to understand people’s theories and arguments in terms of buildings. This idea is foundational to my understanding. I demolished his case by destabilizing his assumptions. I built my argument and supported it with further examples. I constructed a defense for the position; the structural weakness of her theory can be seen at this point; their position was shaky; my view was robust; his argument collapsed under cross-examination. This controlling image isn’t particularly harmful, and it isn’t particularly illuminating, but it constrains our thinking more than we realize (as evidenced by the fact that all of us do it, and very few of us even notice). Metaphors matter.

Consider a different example, where the influence of the controlling metaphor might be more of a problem. Politicians use the language of war in all sorts of nonliteral settings. We have wars on terror, on poverty, on drugs, on obesity, on waste, and apparently on an ever-increasing number of abstract nouns. We must fight this, we are going to defeat that, the real battlefield is here, and so on. The war metaphor is familiar, and so it manages to relieve some of the sense of fear and discomfort we are experiencing (this menace is out there, and it is a genuine threat, but don’t worry everyone, we will conquer this enemy). It also focuses the mind, implying an immediate and serious threat to our well-being as a society, and therefore the need to make the matter in question a top priority, even if it demands costly commitment and sacrifices. At the same time, the concept of war encourages us to think in very binary terms—good guys and bad guys, heroes and villains, enemies to be defeated and territory to be defended—which, when oversimplifying complex problems, has backfired in various ways in the war on terror and the war on drugs. It raises the rhetorical stakes and rallies people to a cause, but turns everyone into opponents or allies, when many are neither, or perhaps even both (a point which is made powerfully in movies like Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic and Peter Berg’s The Kingdom).

But now imagine that instead of employing military metaphors when speaking about a problem like, say, poverty, we employed a fabric metaphor instead. Say we talked about the frayed edges of society and recovering the stitches we once dropped. Say we lamented the unraveling of communities, addressed the knotty tangles of social problems, and argued that belonging to close-knit families was a crucial thread in the fabric of society. That metaphor might cause us to think and act rather differently. It would subtly teach us to think of our problems less in terms of opposition to an external enemy and more in terms of our interconnectedness and the importance of maintaining the integrity of society’s relationships. It would alert us to the delicate character of social problems and of the need for patience, care, and measured action in addressing them, lest tangles become knots by being pulled too hard, or dropped stitches lead to unraveling by being ignored for too long. On the face of it, the only change would be our choice of metaphor—but the implications could be substantial.

The point is this: metaphors have great power to fashion the way we conceptualize things, even when we don’t notice they are doing it. If a controlling metaphor is chosen well, it has the capacity to illuminate new worlds of meaning and help us see all sorts of connections we might otherwise have missed.

So it is with Scripture and music.

• • • •

A musical approach to Scripture encompasses a number of aspects, each of which can help us see Scripture in a fresh light. One, which we have already mentioned, involves the language of tension and resolution. Sometimes two or more books of the Bible, or even two or more parts of the same book, seem to clash with each other, and no resolution is obvious. Yet as the biblical piece develops, we find new themes being introduced, which bring the various instruments together, rearrange things somewhat, and resolve with a harmony that does justice to all of them. Sometimes the clashes are sustained and deliberate and uncomfortable to listen to, but they point forward to a future moment when things will be brought back together again by the master Composer. Scripture, in that sense, is true like jazz.

Another aspect of the music metaphor is the relationship between melody and harmony. The Bible has a clear storyline, a melody, a tune, and it can be summarized (or sung) by a small child. It also has a range of individual and corporate stories that run together, sometimes taking center stage, sometimes fading into the background, providing harmony and counterpoint, treble and bass, height and depth, in such a way that no single writer (or musician) could possibly represent it all. Like Beethoven’s famous “Ode to Joy,” the Bible is both memorably simple, even catchy, and incredibly intricate at the same time. Biblical study is about exploring the detail of the harmony—Why is the oboe, or Obadiah, doing that, and how does it contribute to the whole piece?—without losing sight of the melody. Biblical meditation is about listening to the music for enjoyment, not mere interest, to the point where we dance to its rhythms, sing its choruses, and whistle its melodies on the bus into work.

A third (and more subtle) aspect is the interplay between rhythm and meter. Meter is the underlying time structure of a piece, whether it is audible or not—one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four—and although it may vary within the piece, it provides a grounding in time, a sense of orientation, for the listener. Rhythm is the structure of the sound you actually hear—boom, ba-cha, boom, boom, ba-cha—which may involve a number of notes in one beat, or a number of beats without notes. The rhythm rides the meter like a surfer rides a wave, playing, doing its own thing, but always mindful of and constrained by the steady movement underneath.

Scripture works in a similar way. Chronologically speaking, every day is as long as every other day, with the passing of weeks, months, seasons, and years providing a meter for the piece as it unfolds. If we want to, we can form timelines from the Bible, reconstruct histories, and synchronize dates with external sources. But the rhythm of Scripture is not like that. Strong, accented, audible beats dominate the rhythm—Sabbath, Passover, the Day of Atonement, Pentecost, and the like—and they form regular patterns that draw repeated attention to particularly important moments in the story. And because the rhythm is repeated so much, every time we hear it, we are somehow transported back to the first time we heard it and forward to the next. So when Mary approaches the tomb early in the morning of the first day of the week, while it is still dark, we are swept back to the first day of the very first week, while it was still dark, and we anticipate the Word of God shattering the darkness: “Let there be light!” From then on, as the first day of the week becomes the Lord’s Day, we look back to creation and back to Easter, and simultaneously look forward to the day when all darkness will become light, and death will be finally swallowed up in victory. Metrically speaking, all beats are equal. Rhythmically...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Wheaton |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Pastoraltheologie | |

| Schlagworte | Ancient Egypt • Ancient World • Baptism • Battle • Bible • Bible book • Bible story • Biblical • Christian • Christianity • christian living • Creation • Deliverance • Egypt • Elijah • exile • Exodus • Faith • Forgiveness • freedom • gods grace • gods people • gods plan • Gospel • Holy Book • immorality • Jesus • Literary Analysis • Moses • Old Testament • Oppression • pharaoh • priesthood • Prophecy • Prophet • Purity • Redeemer • Redemption • Sacrifice • Scripture • Sin • Slavery |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4335-5801-7 / 1433558017 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4335-5801-6 / 9781433558016 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich