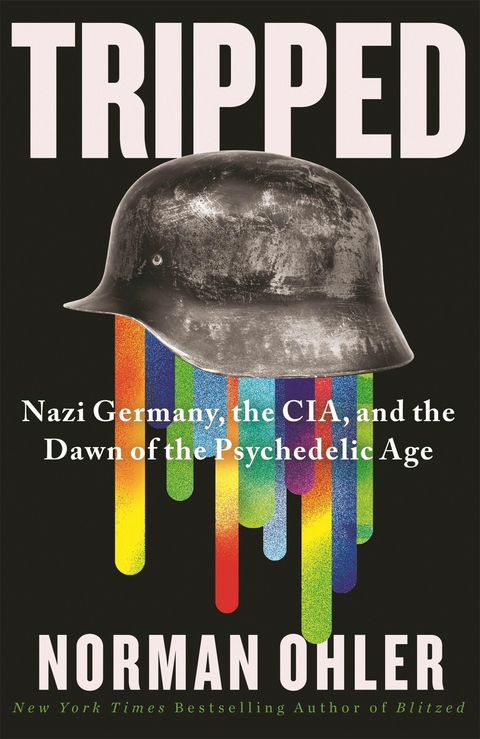

Tripped (eBook)

240 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-359-1 (ISBN)

Norman Ohler is an award-winning novelist and screenwriter. He is the author of The Infiltrators and the New York Times bestseller Blitzed, as well as the novels Die Quotenmaschine (the world's first hypertext novel), Mitte and Stadt des Goldes (translated into English as Ponte City) and the historical crime novel Die Gleichung des Lebens. He lives in Berlin.

Norman Ohler is an award-winning novelist and screenwriter. He is the author of The Infiltrators and the New York Times bestseller Blitzed, as well as the novels Die Quotenmaschine (the world's first hypertext novel), Mitte and Stadt des Goldes (translated into English as Ponte City) and the historical crime novel Die Gleichung des Lebens. He lives in Berlin.

1

THE ZONE

WHEN THE FEDERAL BUREAU OF NARCOTICS AGENT ARTHUR J. Giuliani took up his post as narcotics control officer in the American sector of Berlin on April 8, 1946, he was thirty-seven years old and spoke, to his credit, a bit of French and Italian, both picked up on the streets of New York, but not a word of German. The former capital of the Reich was on its knees; the wounds carved by British and American bombs on the one hand, Russian artillery fire on the other, were still everywhere present. Rubble formed an eerie street-scape where the ghosts of the past roamed, while the geopolitical conflicts of the future were already making themselves felt and the battered residents were searching for the precious commodity of normalcy. Berlin was a place gone completely out of control, a place it hardly seemed possible to regulate; only bit by bit were the women who made up the rubble crews able to clear the streets and make them passable again. Here was a blasted metropolis in which thousands of people lived in ruins, almost all of them out of work, caught in a state between exhaustion and the exciting prospect of starting life over again from scratch.

The shattered economy created a paradise for grifters and dealers. Anyone in need of the most basic necessities had to turn to the black market, where they could find anything that wasn’t bolted or nailed down, from prosthetic limbs to garters. These illegal markets popped up in more than three dozen locations, East and West, each with their own mixture of suspicion, desperation, and just a hint of gold-rush atmosphere, all manifestations “of the complete despair, confusion and cynicism now reigning in Berlin,” as the Washington Daily News reported.

Hershey bars, graham crackers, Oreos, Butterfingers, Mars bars, Jack Daniels: for consumer goods such as these, war-battered Germans were prepared to part with everything from their Leica camera to their left kidney. A Knight’s Cross for a Snickers! A pocket watch for a bit of margarine. Women got dolled up and offered their bodies as goods for barter. Shady characters paced back and forth, whispering appeals to passersby, several watches on each wrist, an array of medals pinned to the inner lining of their long coats, hats tilted rakishly back on their heads and a cigarette ever dangling from their lips, assuming they could get one. Allied soldiers waved fistfuls of money that they weren’t allowed to send home. A contemporary criminologist summed up the situation around him: “The phenomenon of crime in Germany has reached a level and forms unparalleled in the history of western civilisation.”

What was evident everywhere was a “deprofessionalisation of criminality.” In Berlin it seemed as if everyone had a secret, everyone cheated and swindled; they couldn’t survive otherwise. Illicit dealings were part of the everyday life of the population at large; the underworld exerted an irresistible force of attraction on what was left of decent society. Laws were no longer respected; Hitler’s rigid dictatorship was a thing of the past, and now it seemed like everything was allowed: “an environment where black market dealings are a common form of law violation.” Zapp-zarapp, the Russian loan word for the act of “taking something from someone else with a quick, scarcely noticeable motion,” had become ever present.

The four occupying powers, the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France, had their hands full in this Berlin that was now ruled not by the Nazis but by primal instincts, by the will to survive. “Working parties” were formed among the Allies to deal with various issues, including the urgent question of regulating the drug trade, which had gotten out of control.

One problem was the enormous quantities of narcotics that had been salvaged from the stores of the defunct Wehrmacht or taken from the ruins of bombed buildings and put into circulation: Pervitin, produced by the Temmler company and containing methamphetamine; Heroin from Bayer; cocaine from the Merck company in Darmstadt, supposedly the best in the world; Eukodal, the euphoria-inducing opioid that had been Hitler’s drug of choice, likewise made by Merck. With living conditions as difficult as they were, more and more people took recourse to substances to help them get through the day—or the night. Drug offenses rose by 103 percent in the first six months of 1946, compared to a rise of 57 percent in other crimes. On the black market, “enormous prices” were demanded “for smuggled drugs”: 20 Reichsmarks per injection of morphine; 2,400 Reichsmarks for fifty pills of cocaine, 0.003 grams. Giuliani was troubled by these high margins, fearing that the “profits . . . could be used by the Nazi underground.”

In his final letter to Washington before throwing in the towel, Giuliani’s predecessor Samuel Breidenbach had compared postwar Germany to the Wild West. But the new arrival wouldn’t be rattled so easily. He resolved instead to establish order and lay the groundwork for a new set of drug laws that would be in effect for all of Germany. This was a challenge that the narcotics control officer in his crisp new American military uniform was happy to take on. It didn’t hurt that the War Department paid him a salary that was a fourth higher than what he would have earned in a civilian post. The conflicting interests of the different occupying powers all trying to pull Berlin in this or that direction didn’t faze Giuliani too much as he went about his work. After all, he, being an American, was bringing peace, prosperity, and freedom—and what could be wrong with that?

Not everyone took a negative view of the chaos. The writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger was seventeen years old at the time and didn’t have to go to school because there was no longer any school to go to, not yet anyway. His biographer described the shattered world as a place of learning: “Even without school we can now learn a great deal about politics and society: we learn for example that a country without a proper government can be a very pleasant thing. On the black market, you learn that capitalism always gives a chance to the resourceful. You learn that a society is something that can organize itself without central orders and guidance. In conditions of scarcity you learn a lot about people’s real needs. You learn that people can be flexible, and that solemn convictions may not be as unshakeable as they seem. . . . In a word: in spite of hardship it is a wonderful time if you’re young and curious—a brief summer of anarchy.”

Even Arthur Giuliani, who set up his office at American headquarters in Berlin-Zehlendorf, couldn’t deny his fascination with the unusual circumstances: “It is utterly impossible to realize the completeness of Berlin’s destruction,” he wrote to Harry J. Anslinger in Washington. “Perhaps after years, a fair amount of information can be dug out of the cellars where it now lies buried under the tons of debris which once constituted the buildings above it—but that time is not yet in sight.” He kept himself busy, confiscating something here, arresting someone there, and sending photos back to FBN headquarters as proof of his activities. The photos captured a pair of women’s shoes with hollowed-out heels for hiding narcotics, car doors with armrests full of drugs, potatoes with their insides removed. A Hershey’s cocoa tin filled with cocaine. A ladies’ slip soaked in heroin solution. A book with a hole carved into its pages that in lieu of reading material offered a different kind of food for the brain.

In reality, however, such minor investigative successes had little effect. The problem was structural in nature. After the old National Socialist authorities had ceased to exist, a vacuum had opened up for the illegal dealers to exploit. How was Giuliani supposed to remedy the situation? Then one day hope arrived from an unsuspected source. He received a letter from a former Gestapo agent by the name of Werner Mittelhaus. “It is a long time my intention to write to you because I wish to tell you about the activity of the ‘Reichszentrale zur Bekampfung [sic] von Rauschgiftvergehen’ during the last years of the war.” It was there, at the Reich Headquarters for Combating Narcotic Crime, that Mittelhaus had been employed, and in his accented English he voiced a wish: “I myself would like very much to work again in drug offices . . . I suppose, you will have an interest on such a work in Germany, and I would be glad, if I could cooperate in a common combat of the drug smuggle.” He concluded his offer by saying, “I was never a member of the SS, only a member of the NSDAP on order of my department. The proof of my anti-Nazi positions are in my hands.”

The offer presented Giuliani with an ethical problem: Would he accept help from a former Nazi, profit from his expertise, let the man tell him how to police the streets of Berlin? It was a dilemma that the other Western allies were also caught up in, whereas the Russians made no compromises on this point. Giuliani discussed the idea with Anslinger, who had no scruples about it and gave the green light from Washington. “You might check up on Mittelhaus as being possible good material for our organization.” From Gestapo to FBN.

In fact, the head of the FBN admired the defunct Nazi regime for its strict policy of prohibition. “The situation in Germany . . . was entirely satisfactory,” he wrote. In contrast to the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | B&W integrated photographs |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Zeitgeschichte |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Albert Hoffman • arthur stoll • blitzed • CIA • Drugs • ernesto londono • Germany • Gestapo • Harry Anslinger • Hitler • Jonathan Freedland • LSD • medical corps • Nazi • oppenheimer • psychedelics • SS • Trippy |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-359-0 / 1838953590 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-359-1 / 9781838953591 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich